Census 2021, Pandemic And Delays

The original version of the article was published on 13th January 2023 in “The Daily Guardian”

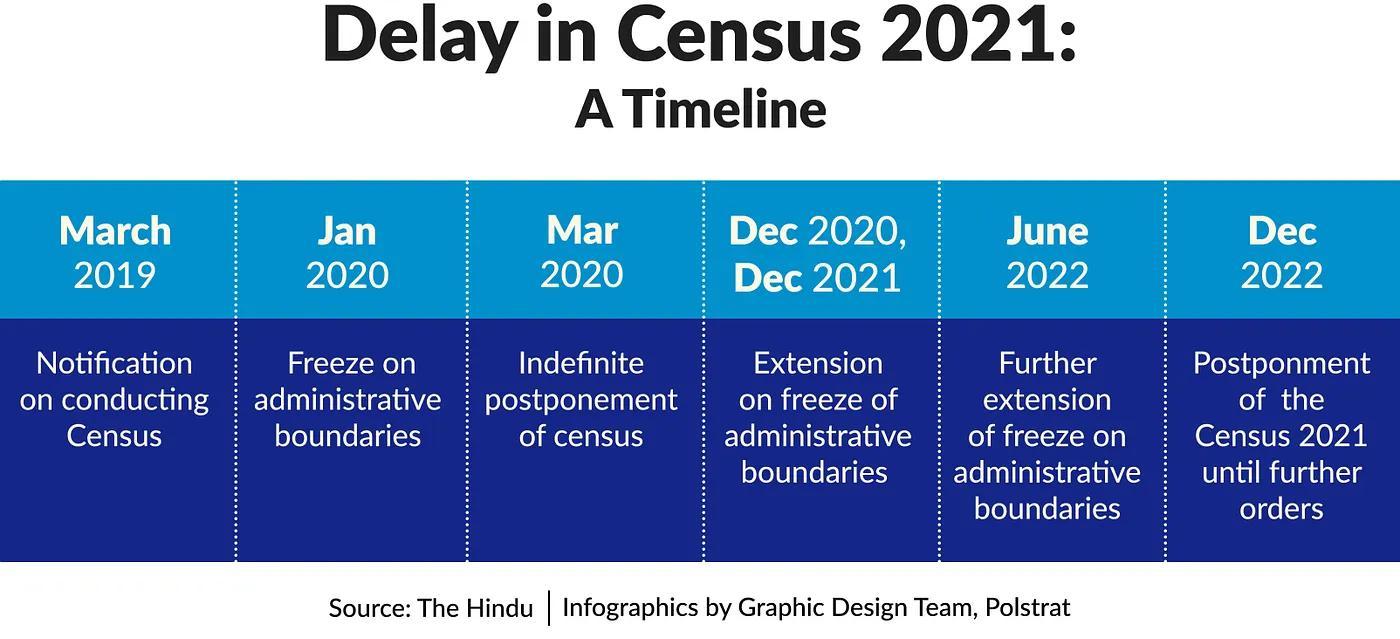

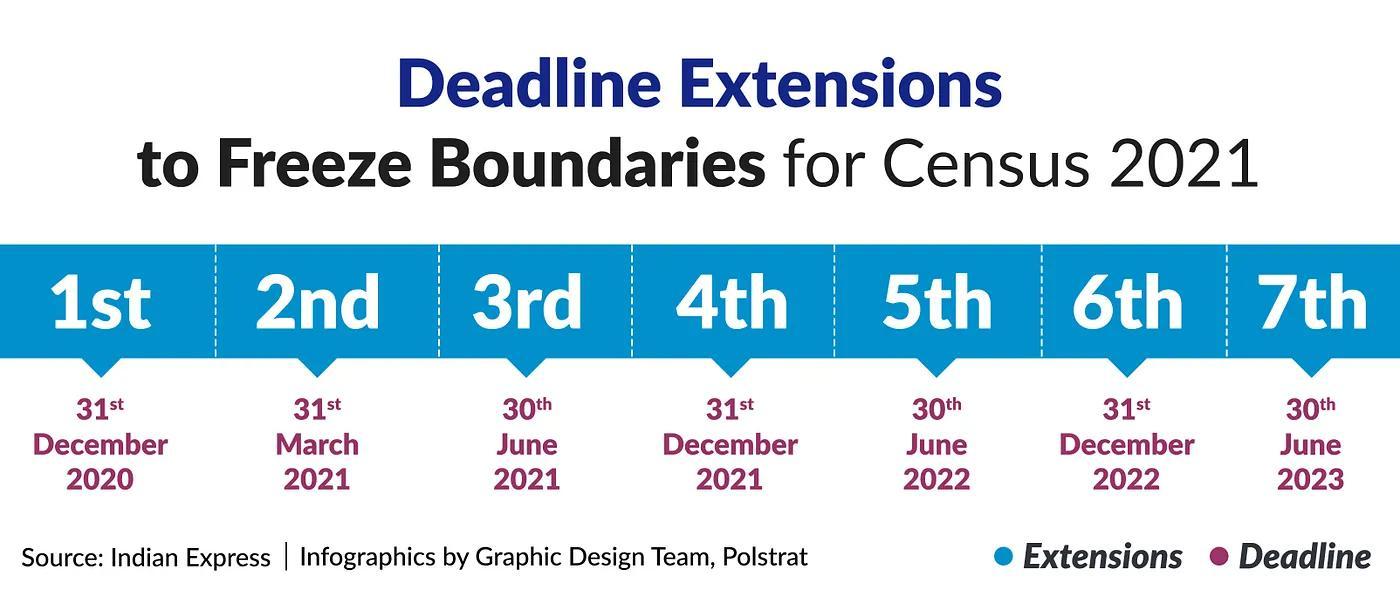

In the first week of January 2023,the office of the Registrar General of India (RGI) extended the deadline for freezing of the administrative boundaries in the country to 30th June 2023. The deadline to freeze jurisdictional boundaries for Census 2021, a necessity before any Census activity begins, has been extended on seven occasions in the past, including till 31st December 2022, and before that till 30th June 2022 on two occasions.

Census in India is conducted on a decennial basis and involves large-scale data collection at the household and individual levels. The census tallies data on several features of the Indian population ranging from basic demography, literacy levels, educational levels, and spoken languages to caste status, religion, marital status, occupation, and migration status, among others. It is vital to administrative functions and is used extensively in planning welfare schemes.

The boundaries of administrative units are frozen three months before the commencement of the Census during which the data is compiled and shared with the Registrar General of India, which then begins its preparatory work for the Census. Owing to the further extension in the freeze of administrative boundaries, the Census 2021 is unlikely to be conducted before September 2023, at the least. Moreover, since the next Lok Sabha elections are due in early 2024, the possibility of completing the census by late 2023 or early 2024 also appears bleak.

We take this opportunity to understand the requirements and importance of a census, how a census is conducted and what is likely to happen in the current scenario of delays.

BIRTH AND LEGALITIES OF CENSUS IN INDIA

The census to enumerate the population was first conducted in India more than 130 years ago, in 1872. This census was not conducted at the same time across the country and is therefore referred to as an asynchronous census. The questionnaire for the 1872 census included just 17 questions and since then the activity has expanded in both scope and scale. The Census 2011 Household Schedule covered a list of 29 questions. The first proper or synchronous Census in India, beginning on the same day or year across the country, was carried out in 1881. Since then, the Census has happened every 10 years except for the 2021 Census which has been delayed on account of the pandemic.

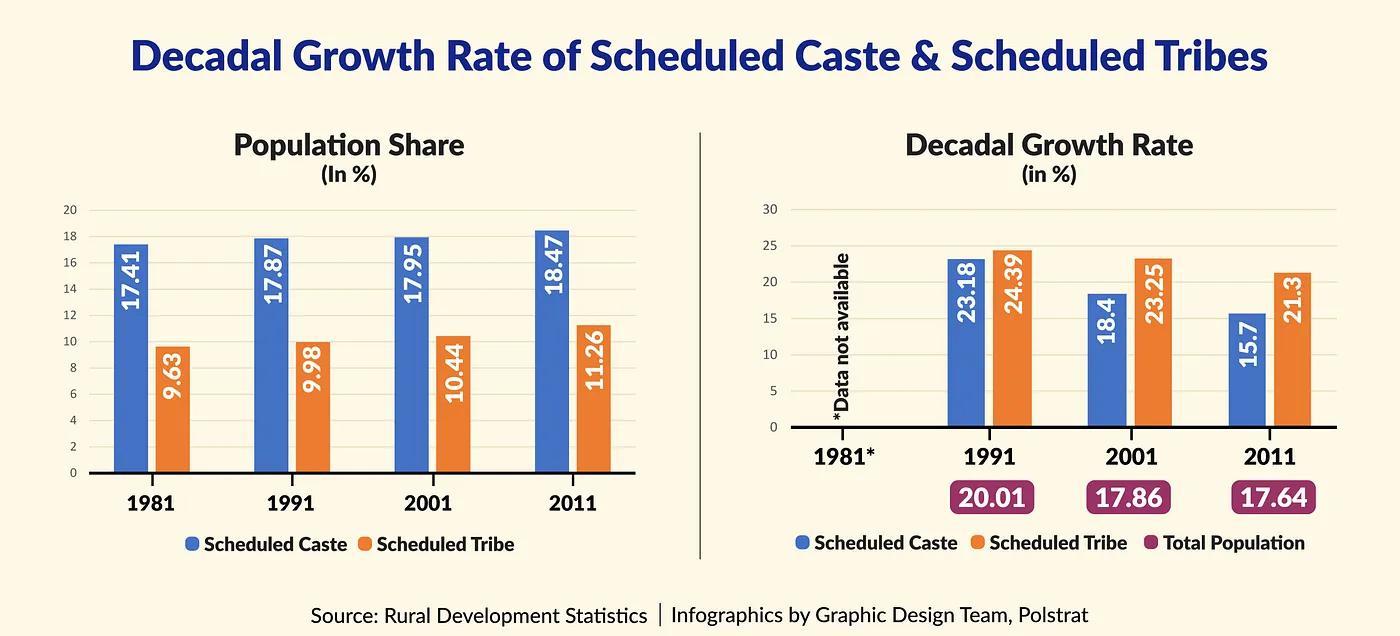

Census is carried out in two phases and begins a few months after the administrative boundaries are frozen. The first phase involves house-listing enumeration to collect data on housing conditions, household amenities and assets possessed by households. The second phase is the actual census activity which collects data on population, education, religion, economic activity, Scheduled Castes and Tribes, language, literacy, migration, and fertility.

Census in India is conducted under the Census Act of 1948, which predates the Constitution. While the constitution talks about the usage of Census data for the delimitation of electoral constituencies and for determining the quantum of reservation for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, it gives no instructions on the periodicity of the census. Moreover, while the Census Act provides the legal background for activities relating to the Census, it also fails to state clearly the periodicity of holding the census and provides no binding requirements on the government to conduct the Census on a particular date or at particular intervals.

NEED FOR POPULATION ENUMERATION

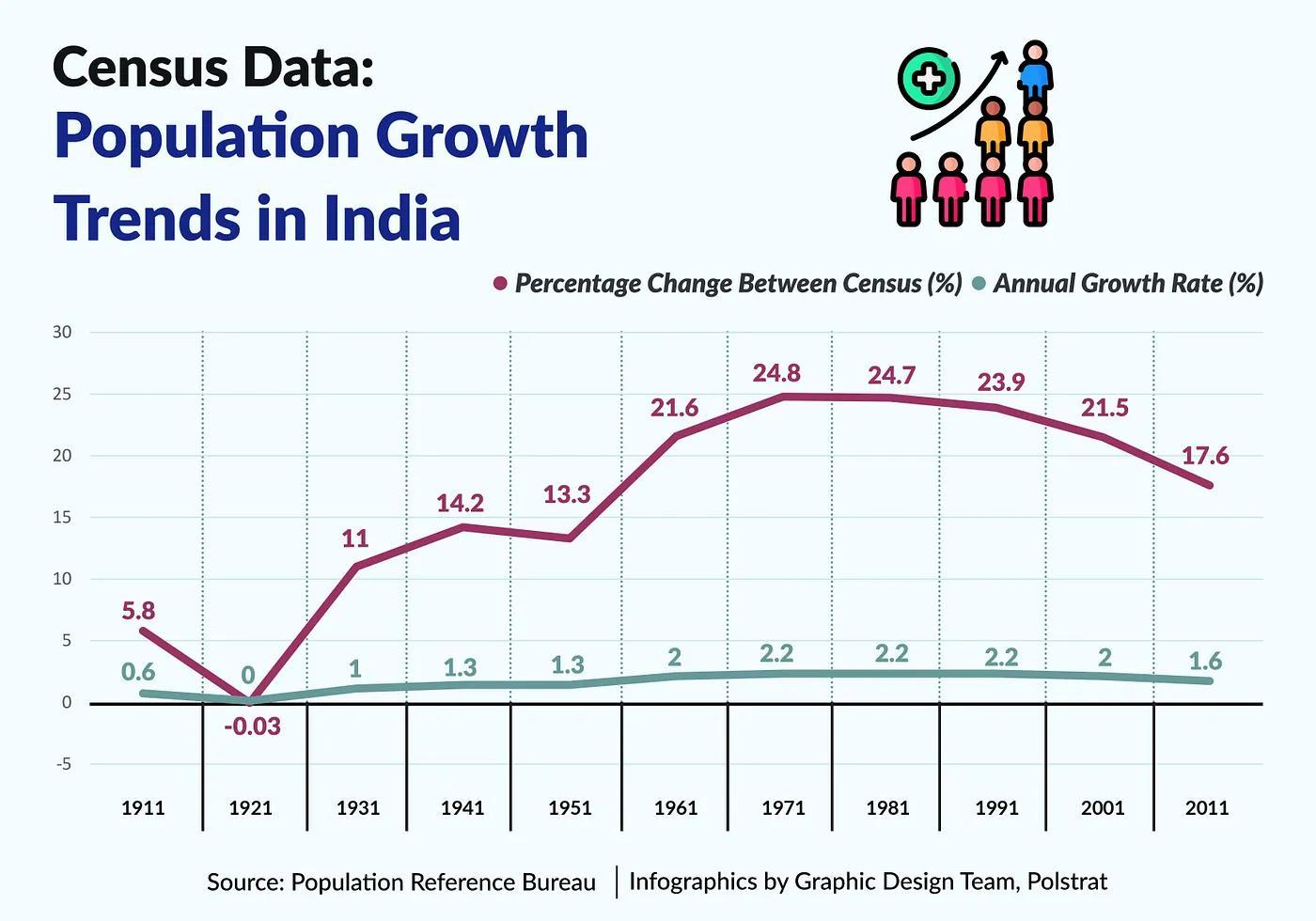

The census is important not only to ascertain the change in population levels across the country. Data from the census is used variedly in socio-economic and policy making decisions across the levels of government in India. Census data is also used by international agencies to estimate the world’s population.

The Finance Commission in India allocates funds to States on the basis of Census figures. Decadal census activity generates trends in regional variations in population and assists in decision-making for the allocation of welfare schemes and programmes. Central allocations by the Union government for states are also often based on the share of population, demographics and the population of specific groups such as SC, ST and OBCs.

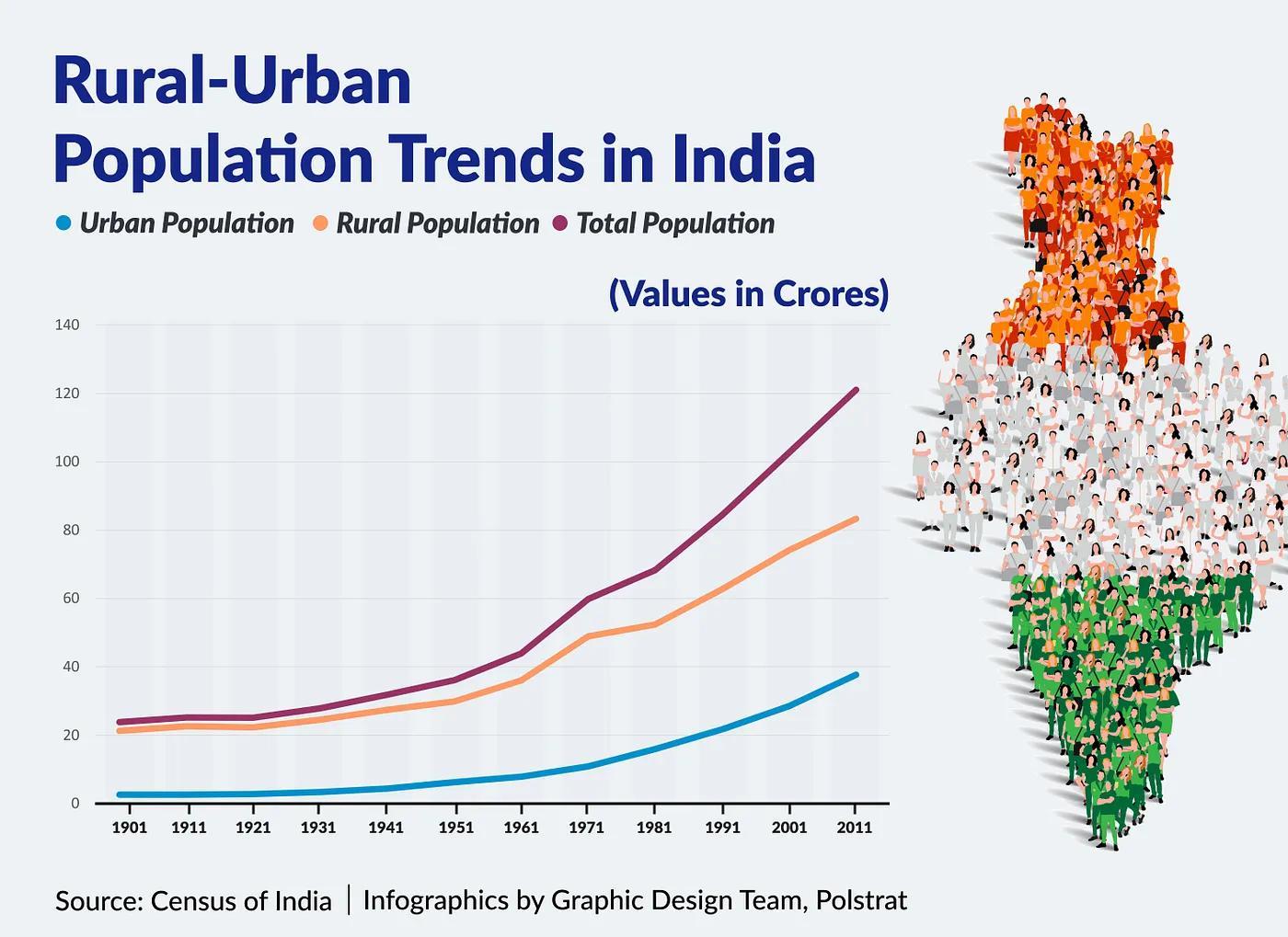

Outdated Census information is often unreliable and affects both the current recipients and those who might now be eligible to receive the benefits of welfare schemes. Moreover, as the standard of living improves across society, census data also helps in ascertaining the population which no longer needs welfare benefits thereby helping shift support to the more needy sections of the population. The most pertinent example of using census data for the allocation of welfare benefits is the Public Distribution System (PDS) under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013. The NFSA currently provisions that 75 per cent of the rural population and 50 per cent of the urban population — totalling 67 per cent of the country’s population — are entitled to receive subsidised food grains from the government under the targeted PDS. The 2011 Census records India’s population at about 121 crores with PDS beneficiaries totalling approximately 80 crores by the 67 per cent ratio.

However, taking into account population growth over the last decade and projecting India’s 2020 population at 138 crores and the 67 per cent ratio as per NFSA means PDS coverage should increase to around 92 crore people. This is only possible when we have accurate census data accounting for not only the increase/decrease in population of the entire country but also the urban-rural population break up and spread of population across states and union territories.

DELAYS IN THE 2021 CENSUS

The current delay in the 2011 Census began in 2020 owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. The first notification for the 2021 census was released by the RGI as early as December 2017. The announcement called for a jurisdictional change in boundaries asking states and UTs to update the changes by 31st January 2020, with 31st December 2020 as the deadline to freeze boundaries for the Census. The house-listing phase of the Census was scheduled from 1st April to 30th September 2020. During this period, the enumeration for the National Population Register, a precursor to the preparation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), was also due to be conducted.

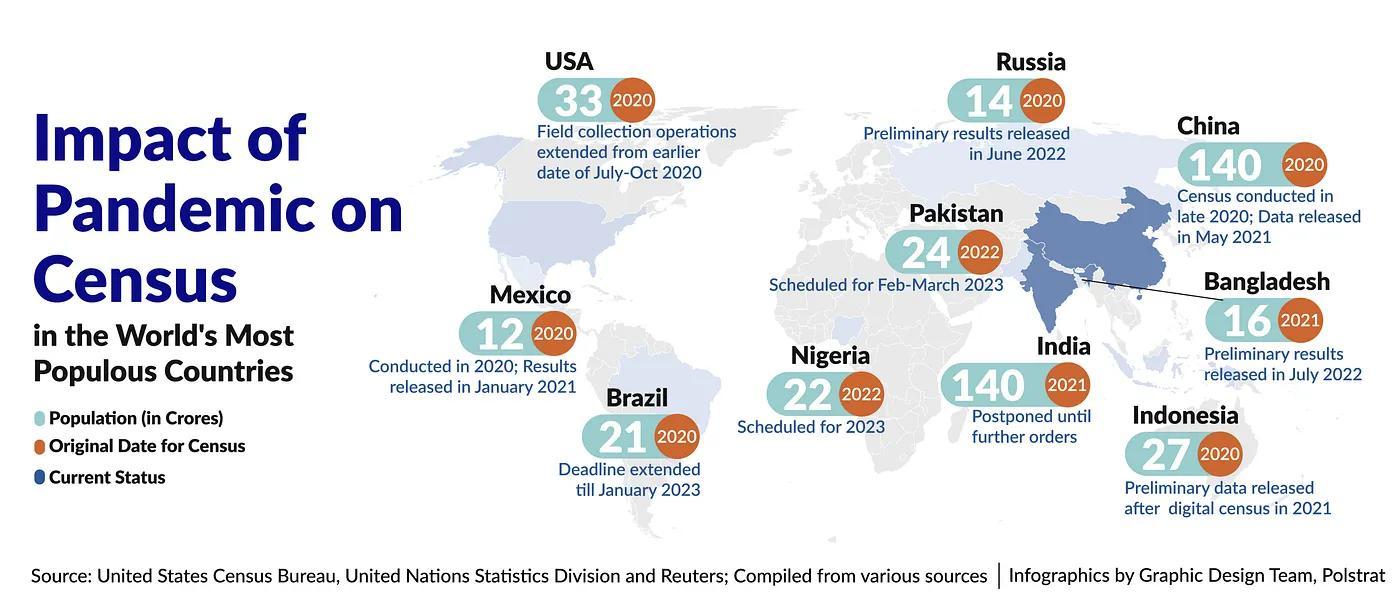

As the country witnessed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the deadline for Census enumeration was indefinitely postponed. Along with this, the deadline for the updation of jurisdictional changes and freezing boundaries was also extended. After the indefinite postponement of the census, states made several requests to allow the creation of new units which would require the registrar general to extend the date of freezing boundaries.

The deadline has been extended six times since the first extension in March 2020. Since the Census enumeration can only begin three months after administrative boundaries are frozen and the completion of the Census in its two phases takes at least 11 months, the possibility of the 16th Census in India being completed in 2023 or early 2024 is highly unlikely.

PRESSING NEED FOR UPDATED CENSUS DATA

Due to porous borders within and between countries, socio-economic realities, and changed public health scenarios due to evolving threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic that affect people at a mass scale, understanding and recording population trends across demographics is key to effective policy formulation and implementation. In India, internal migratory trends, shifts in population from urban to rural areas in search of better opportunities and the general trends of increasing urbanisation with improvement in public infrastructure and shift in economic activity from primary to secondary and tertiary means the country is in a phase where transitory changes are happening at a fast pace and in a short period of time. In spite of this, a large share of India’s population remains largely out of the ‘development net’ and is in desperate need of government support in every way possible. The provision of government support for the weaker sections of society is only possible through accurate data on the concentration of this population and their requirements for a better life.

Currently, government agencies continue to rely on decade-old Census 2011 data for the implementation of welfare benefits. To facilitate the smooth planning and implementation of administrative and welfare measures and statistical management for governance, an updated Census that accurately enumerates the trends and changes in India’s population is the need of the hour.

Damini Mehta/New Delhi

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.