Does India need Mosquirix: World’s first approved vaccine against Malaria

The vaccine’s availability in high incidence regions of the world such as India will go a long way in eliminating the incidence and the burden of malaria

On 6th October 2021, the World Health Organisation (WHO) approved the world’s first anti-malaria vaccine called the RTS,S or Mosquirix. The vaccine, in the making since 1987, was developed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the London-based pharmaceutical firm GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). In 2019, an estimated 22.9 crore cases and 4.09 lakh deaths related to malaria occurred worldwide. Moreover, children under five years of age are the most vulnerable group affected by the disease.

According to the WHO, India has an estimated burden of 1.5 crore malaria cases with 19,500–20,000 deaths annually. Out of this, roughly just 20 lakh cases and 1,000 deaths are actually reported each year. Mortality from the disease varies notably from state to state. For instance, in Vellore, Tamil Nadu the mortality is only 7.9%, whereas, in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, and Rourkela, Odisha, it is as high as 25.6% and 30%, respectively. It is difficult to control the spread of the disease due to such a high variation in incidence and mortality across states and districts. In such a scenario, the vaccine, with the brand name Mosquirix will act as a first-hand tool for prevention against a disease discovered nearly 130 years ago.

What is Mosquirix?

Mosquirix or RTS,S/AS01 is a recombinant protein-based malaria vaccine. It is the world’s first malaria vaccine and the first vaccine to address the parasitic infection. The development of the vaccine began 30 years ago in 1987 and involved a cost of more than US$750 million. The WHO’s recommendation of the vaccine is based on an ongoing pilot vaccination programme in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi since 2019. More than 23 lakh doses of the vaccine have been administered in the three African countries to date.

According to the pilot programme, the vaccine’s efficacy ranges from 26 to 50% in infants and young children. While it has led to a 30% reduction in severe and deadly malaria cases, it has a modest efficacy when compared to other childhood vaccines. The vaccine has the potential to make a significant dent in the disease burden, which, according to the WHO’s World Malaria Report 2019, killed an estimated 4.11 lakh people in 2018 alone.

Need for a Malaria Vaccine

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes but is both preventable and curable. According to the WHO, vector control is the most effective method to prevent and reduce malaria transmission and it mainly recommends two forms of vector control measures– insecticide-treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying. Despite all the measures to control the disease, in 2019, nearly half of the world’s population was at risk of malaria. Children under five years are the most vulnerable group and accounted for 67% of total malaria deaths worldwide in 2019. In the initial phase, the vaccine will specifically target children.

Since 2000, the progress in malaria control has been primarily due to vector control interventions. However, increasing mosquito resistance to insecticides coupled with ease in the transmission of the disease has threatened these gains marking the increasing need for a malaria vaccine in fighting the disease.

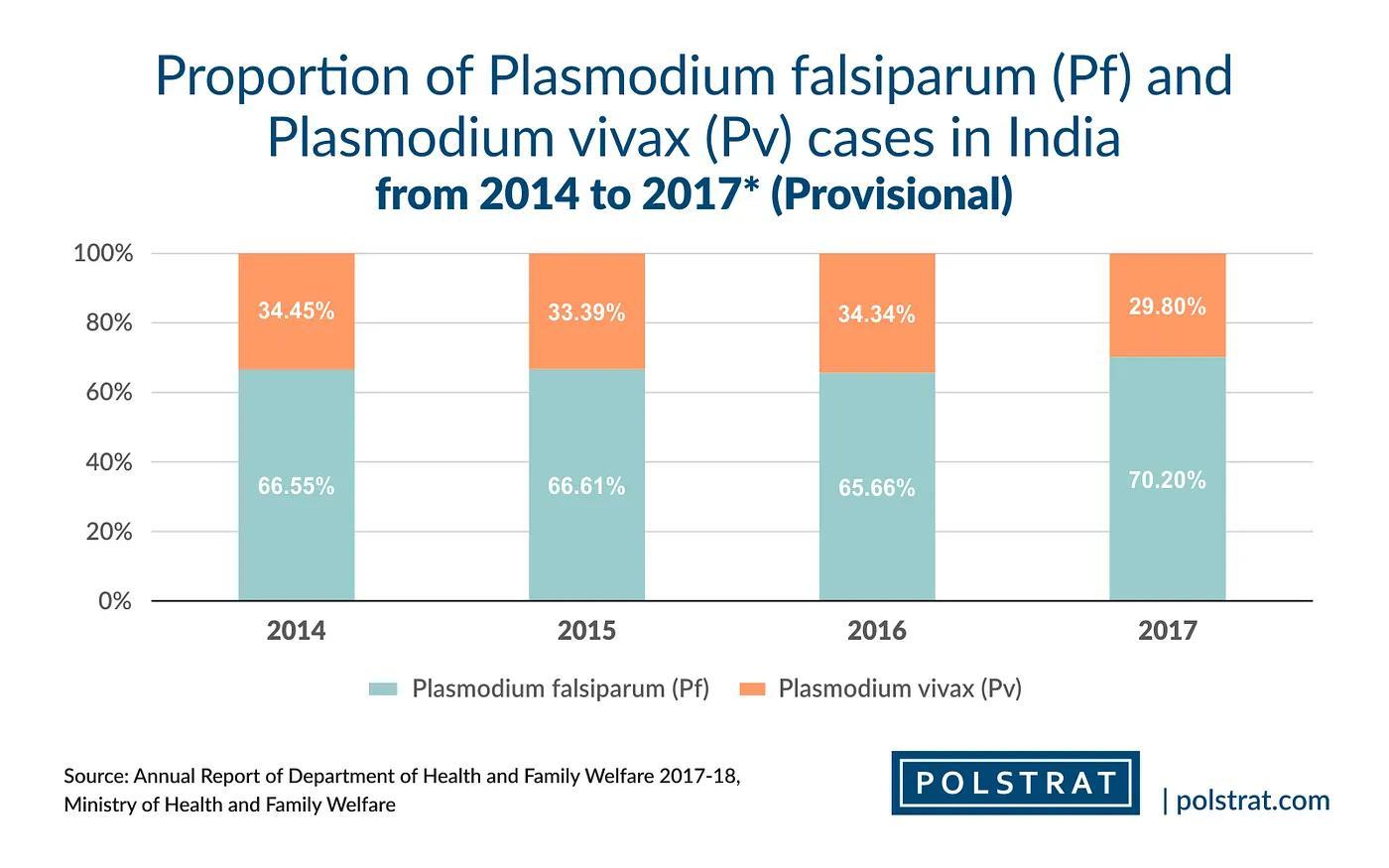

In October 2021, the WHO endorsed Mosquirix for “broad use” in children in sub-Saharan Africa, home to the deadliest malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, making it the first malaria vaccine candidate to receive this recommendation. The vaccine acts specifically against P. falciparum, the most deadly malaria parasite globally. In 2018, P. falciparum accounted for 99.7% of estimated malaria cases in the WHO African Region, 50% of cases in the WHO South-East Asia Region, and 71% of cases in the Eastern Mediterranean.

India’s Malaria Burden

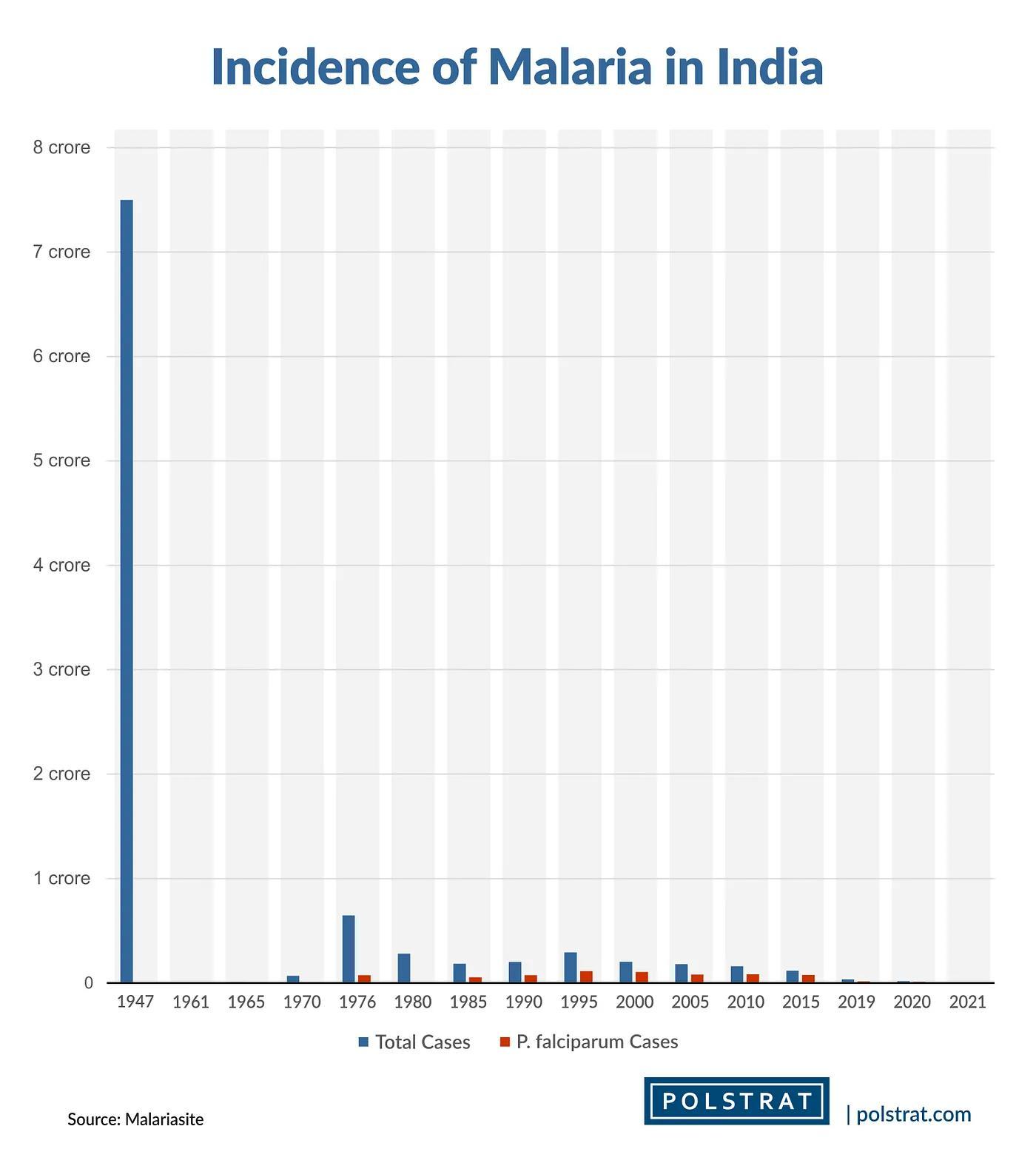

In the fight against malaria, India has come a long way since independence. After several initiatives undertaken by the government, malaria cases dropped from an estimated 7.5 crores in 1947 to a mere 49,151 in 1961. However, the late 1960s saw a countrywide resurgence in cases of malaria owing to the mosquito’s resistance to insecticides and the parasite’s growing resistance to antimalarial drugs. As a result, anywhere between 20 to 60 lakh malaria cases were reported yearly from 1970 to the 1990s. The cases dropped gradually to around 20 lakh a year by the late 1990s. Between 2005 and 2015, malaria cases in India remained in the range of 8 to 15 lakh every year. Since then, ending malaria has remained a top priority for the government as it launched the National Framework for Malaria Elimination (2016–2030) in 2016 with the target of a malaria-free India by 2030.

The National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP), launched in 2003, integrated malaria control with other vector-borne diseases. The programme adopted common strategies such as chemical control (eg. indoor residual spraying), environmental management, biological control (eg. larvivorous fish), and personal protection strategies (eg. insecticide-treated bednets) to control all such diseases. As a result of the continued efforts, India reported the world’s largest absolute reduction in malaria cases from about 2 crores in 2000 to 56 lakh in 2019 (according to the WHO’s World Malaria Report 2020). However, malaria cases officially reported in India continue to remain much lower.

Initiatives such as the National Framework for Malaria Elimination (2016) and the National Strategic Plan for Malaria Elimination (2017) introduced large-scale implementation and use of insecticides in states and districts with a high incidence of malaria. Owing to these measures, India achieved an 83.34% reduction in malaria morbidity and 92% reduction in malaria mortality rates between 2000 and 2019. Through this, India also attained Goal 6 of the Millennium Development Goals which called for a 50–75% decrease in malaria case incidence between 2000 and 2019.

Why India needs a Malaria Vaccine

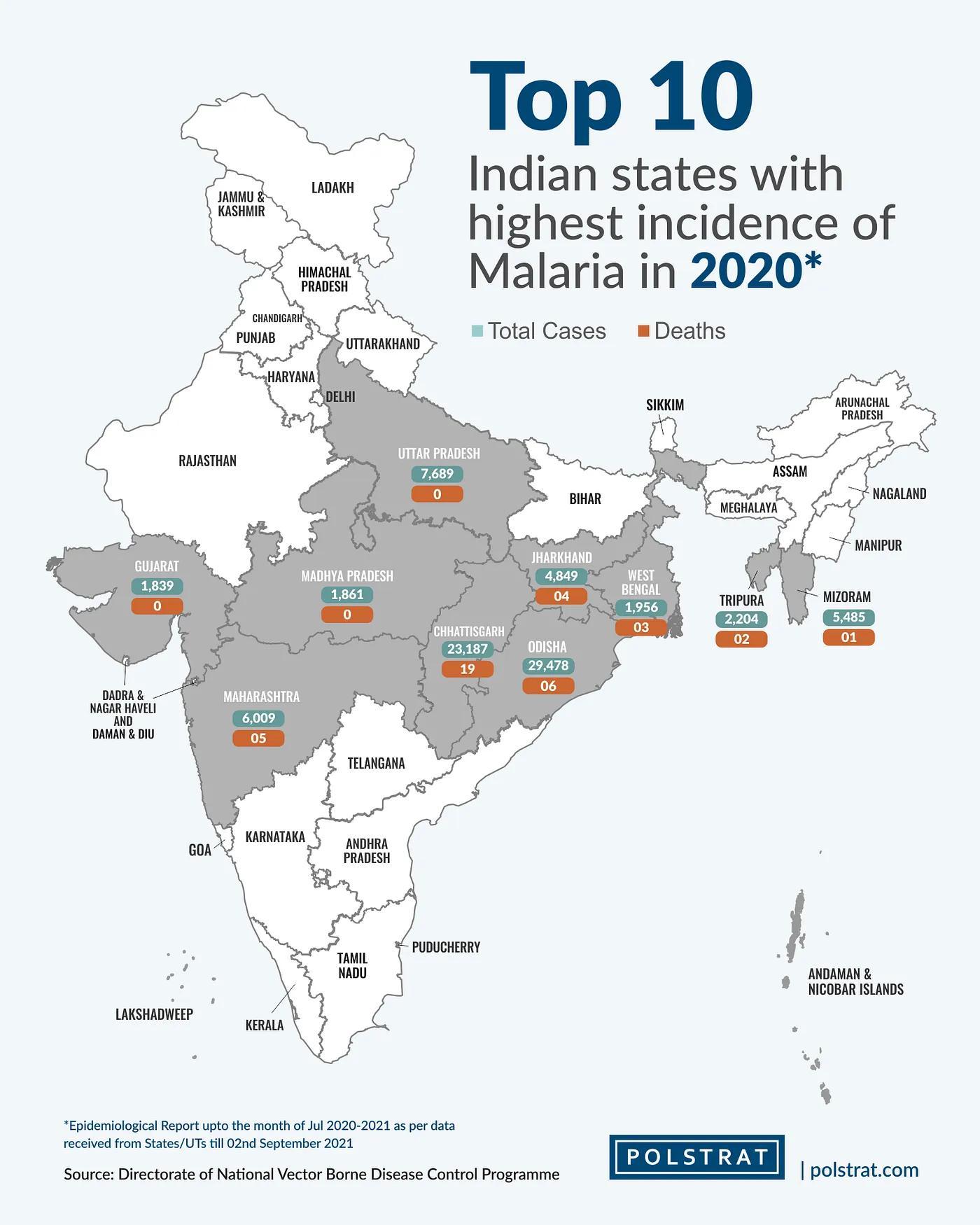

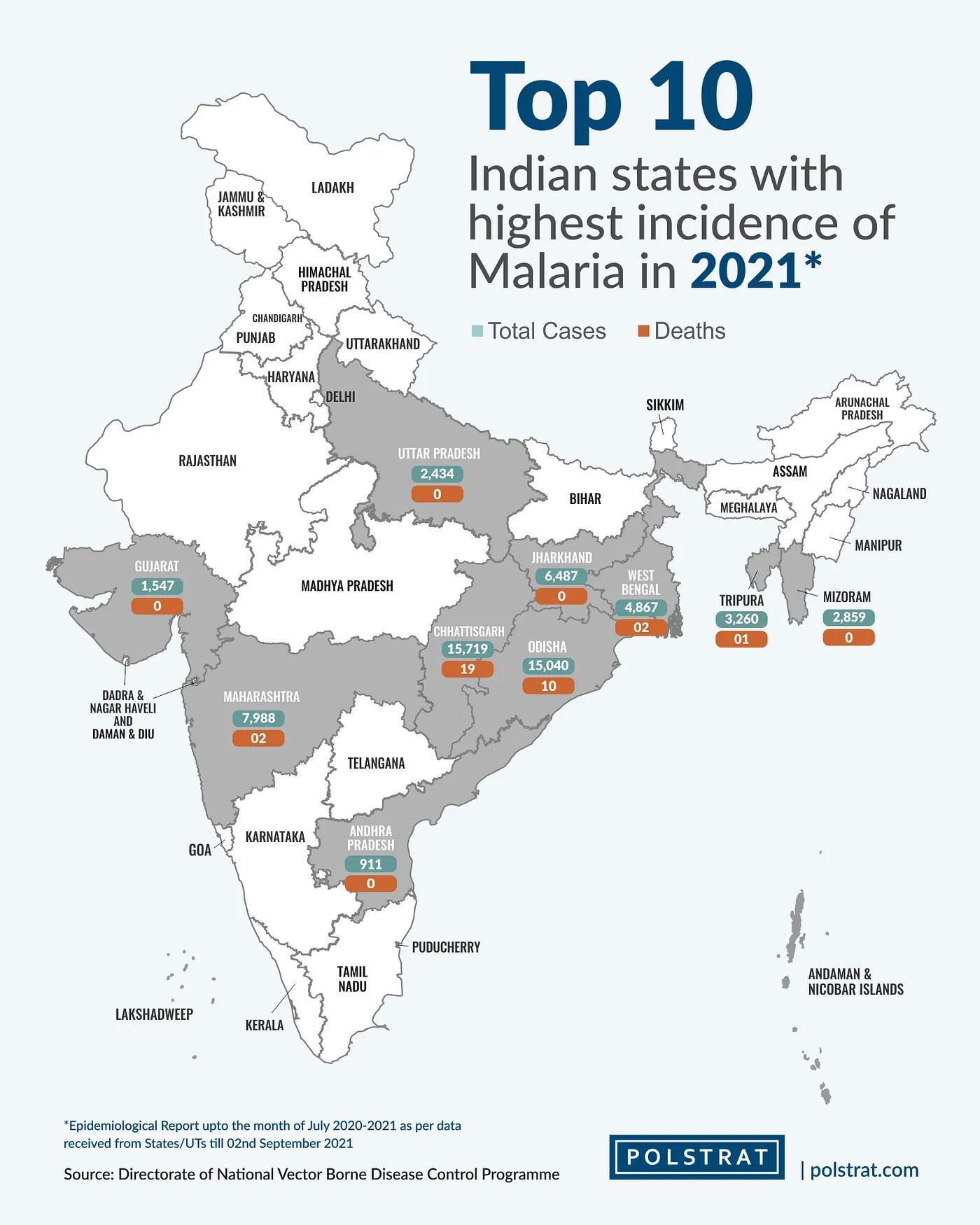

For India, the malaria vaccine could be effective in controlling the incidence and burden of disease in high prevalence states such as Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, and Madhya Pradesh. These states accounted for nearly 45.47% of malaria cases and 70.54% of P. falciparum malaria cases in 2019. In the same year, these states also accounted for 63.64% of malaria deaths in India. Increasing incidence of Plasmodium falciparum variant, which is sometimes prone to develop severity in disease and death, makes the need to control the disease even more urgent.

Additionally, Bharat Biotech’s dominance in manufacturing the Mosquirix vaccine will place India at the centre of this initiative. By 2029, Bharat Biotech is slated to be the sole global manufacturer of the vaccine. It is the global technology transfer recipient from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). According to some experts, a pan-India rollout of the vaccine would not be necessary. Keeping in mind India’s goal of eliminating malaria by 2030, the government should focus on vaccinating people in high burden states and districts.

There are some reservations about the efficacy of the vaccine in controlling the disease in India. According to some experts, since the Mosquirix vaccine acts only on the falciparum variant, it will be of limited benefit in India. The vaccine’s low efficacy also limits its chances of inclusion in India’s vaccination programme as a vaccine has to show at least a 65% efficacy to be included in India’s programme. Moreover, because of malaria’s sensitivity to rain and other such weather conditions, the need to continue implementing preventive measures such as spraying insecticides to get rid of the malaria parasite cannot be discounted even after the vaccine is introduced.

There is a huge gap between the malaria cases and deaths that are reported and the actual number of cases and deaths that occur in India. This leaves room for interventions such as the malaria vaccine that can help overcome the poor implementation of other preventive measures and the poor availability of treatment, especially in high incidence regions. In high malaria incidence states, most cases are reported from tribal populations living in foothills, forested or conflict-affected areas where control of mosquito population is difficult given the environmental conditions. Since the implementation of preventive measures such as nets and spraying insecticides is challenging in these areas, the vaccine will help create a wall of protection.

When will the Vaccine be available in India?

According to industry experts, the vaccine for malaria will take anywhere between two to four years to hit the Indian market. Indian firm Bharat Biotech is due to receive the technology for the production of the vaccine from GSK and will be the sole supplier till 2029. Most of the vaccines will be targeted initially in African countries with nearly 1.5 crore doses provided annually. However, according to some sources, it would take a few years before the vaccine becomes available either in African nations or in India.

The vaccine’s availability in high incidence regions of the world such as India will go a long way in eliminating the incidence and the burden of malaria. Although India’s share in the overall malaria caseload is only 3%, the economic ramifications of the disease burden are huge. In total, the disease cost the country around 1.42 lakh crore rupees, according to estimates from 2014 published in the WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health by Indrani Gupta and Samik Chowdhury.

Damini Mehta /New Delhi

With inputs from Animesh Gadre, Damayanti Niyogi and Riya Peter, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.