Elections 2021: Busting Myths about Election Malpractices

Note: The original version of the article was published on April 14th in “The Daily Guardian”

Elections in India are not run any differently from how the parliament itself runs, covered in allegations between members and parties. While allegations are standard practice of campaigning (indeed politics) and often unfounded, there are many instances of malpractice during elections regardless of the guidelines issued by the Election Commission of India (ECI). From the purchase of votes, violence, excessive election spending to campaigning within the last 48 hours of voting, there are instances of candidates flouting all rules. Much research has been done on the effectiveness of paying for votes directly to voters in the form of cash or goods which shows us that the effectiveness is undecided and often negated thanks to the secret ballot.

In this column, we will look at some major allegations which are taken up at a large scale and look at the reality on the ground. The contrast of speaking out against corruption during campaigns and at the same time disregarding the model code of conduct set by the ECI provides a glimpse into the workings of politics in the country. Though we have come a long way from mass booth capturing and dumping of votes there still are many aspects of the election process that we as a country need to improve. When the validity of electronic voting machines (EVMs) was questioned, (voter-verified paper audit trail) VVPATs were introduced to ensure fair voting. The ECI actively works on handling complaints swiftly and even holding re-elections in areas but the complex systems in place for the largest elections in the world still have ways to go to ensure there is no truth left behind these allegations.

Cash for Votes and EVM Hacking: The Truth Behind Allegations

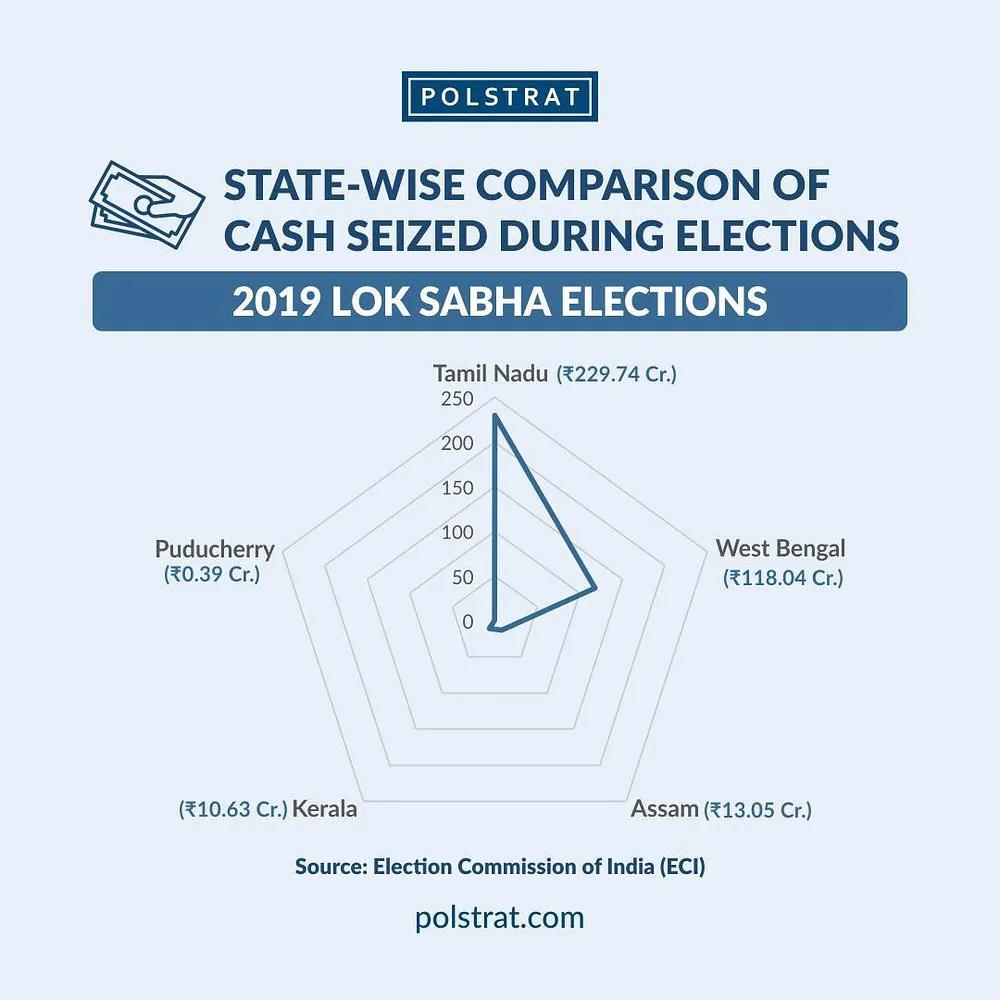

On April 6th, as voting closed for assembly elections in various states in India, including Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, West Bengal and Assam, reports of clashes between political parties from almost every part of the country came to light. Parties accused each other of buying votes for cash, liquor, freebies and of orchestrating electoral fraud by tampering with electronic voting machines (EVMs).

Such allegations during any election in India are not new at all and have become a standard feature of every bypoll, assembly and state election in India. Another common form of electoral malpractice in India is the violation of the model code of conduct as prescribed by the Election Commission of India (ECI).

The ECI, a constitutional body under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Law and Justice, the Government of India is responsible for the conduct of elections at the national level, state level and local level. The ECI is responsible to ensure that any instances of electoral malpractice and fraud are kept under check as per various laws to ensure that everyone has a level playing field. Let us take a deep dive into these accusations and find out what is the truth behind them.

What is the price of a vote in India? The barter for cash, liquor, gold for votes.

On April 5th, before the single-phase voting was set to begin in Tamil Nadu, residents of a village in Namakkal district held a protest. The reason? The protesters alleged that they had been left out when a political party was distributing cash for votes for polling the next day. Clashes were witnessed on polling day between several political parties in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala accusing each other of giving out cash for votes. Undoubtedly, distributing cash and other freebies such as liquor, narcotics for votes has become a commonplace practice in Indian elections.

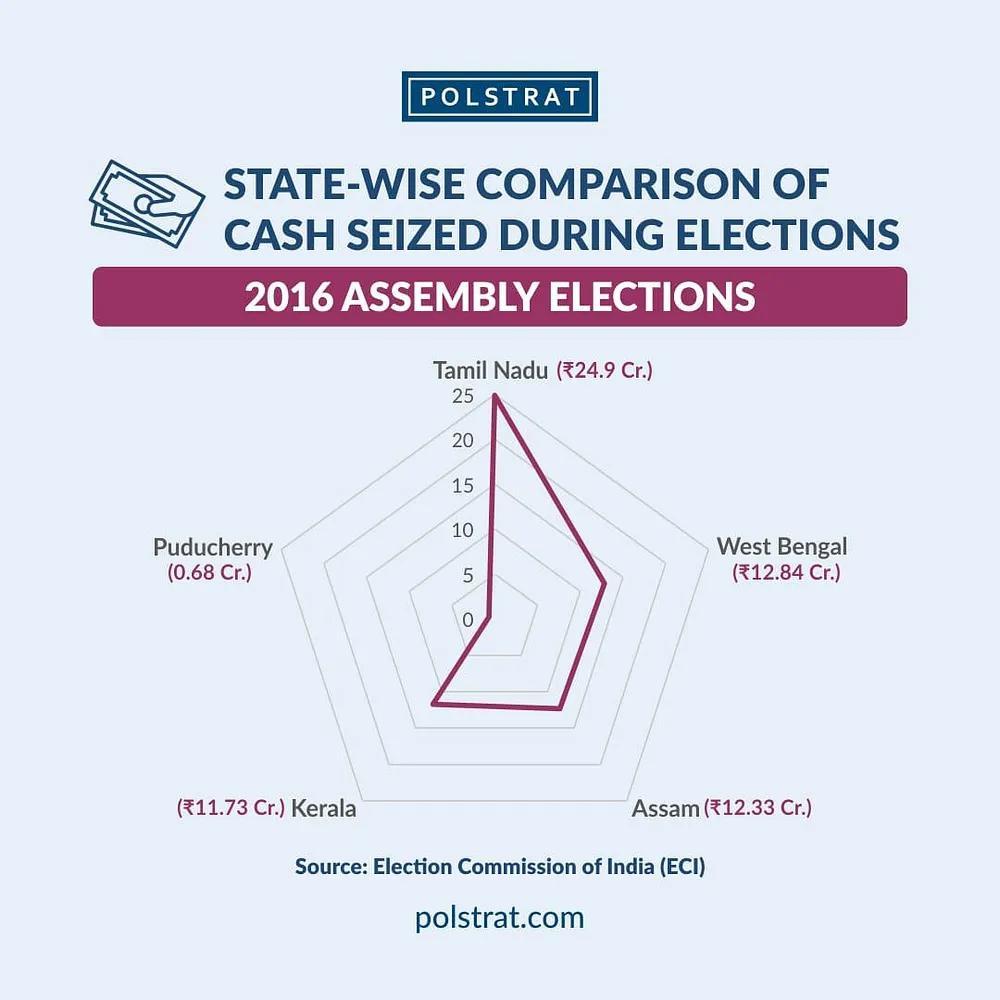

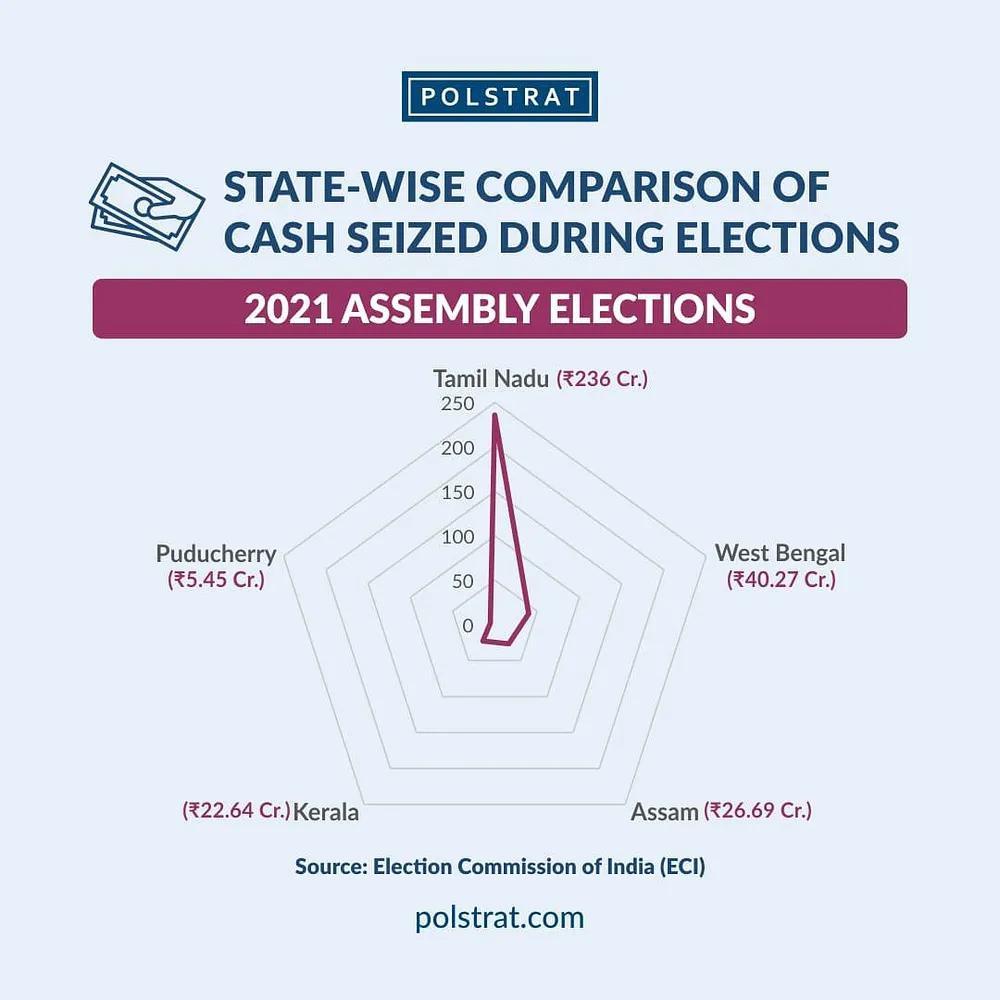

The distribution of any cash, gifts, liquor or other items is not permitted when the election model code of conduct is in force by the Election Commission of India. It falls under the definition of ‘bribery’ — an offence under Section 171 (B) of IPC — and Representation of the People Act, 1951. However, despite this, as per data provided by the ECI, roughly three times as much cash, liquor, narcotics and other freebies have been seized so far in 2021 as compared to during the assembly elections in 2016 in the same states.

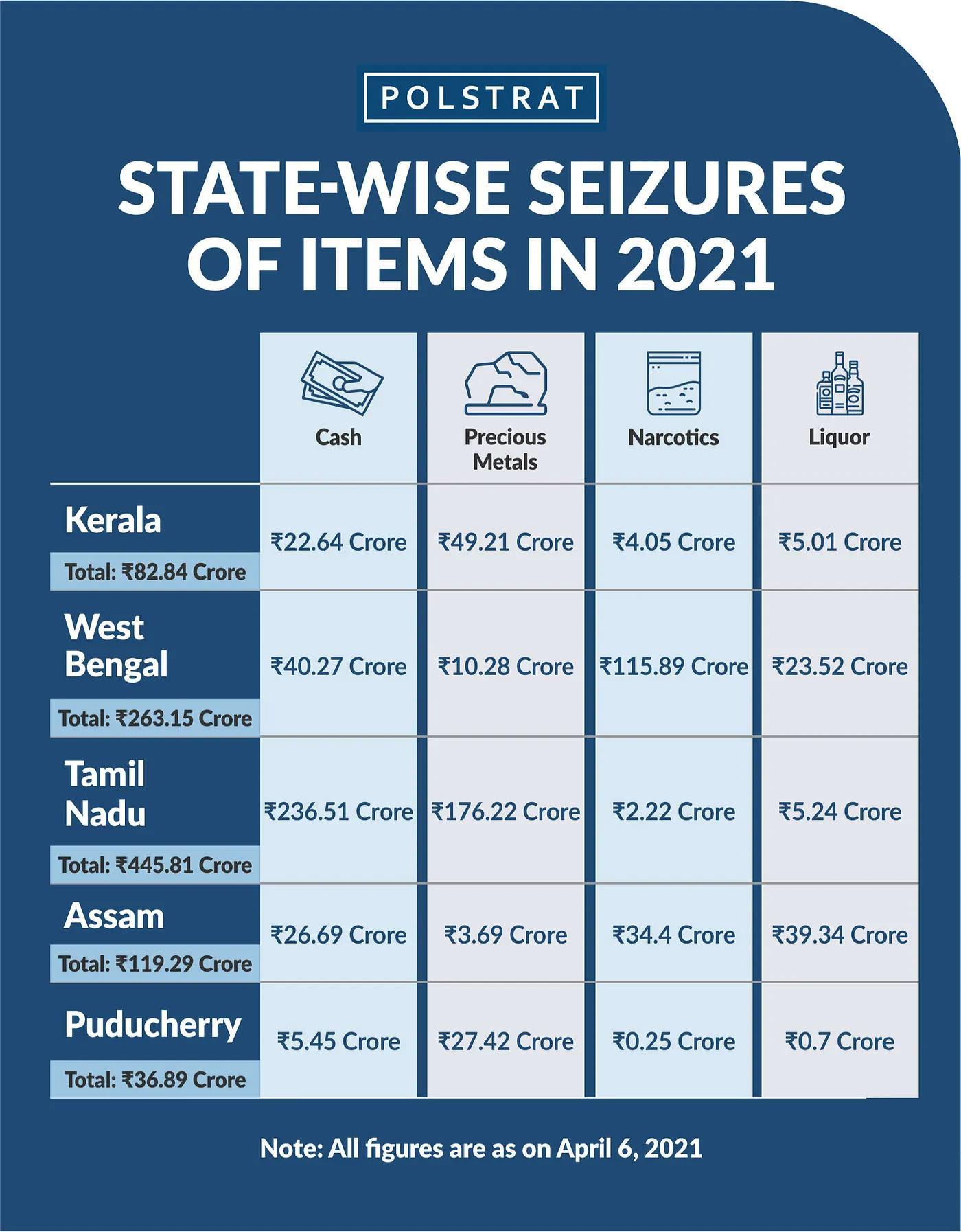

Till April 6th (before the day of polling) the ECI has roughly seized unaccounted cash, liquor, narcotics, precious metals and other freebies worth Rs. 948 crores from all poll-bound states. In 2016, the same figure was at around Rs. 226 crores. Out of all the freebies seized, cash accounted for the highest percentage (Rs. 331.56 crores), followed by precious metals (Rs. 226.82 crores).

In fact, the exchange of cash and freebies for votes is so common that many politicians have talked about the “going rates” for a vote during elections. In a report written in the Scroll during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, a politician from Arunachal Pradesh remarked, “Last time, I wanted to contest, so I did a recce … the rate was Rs 20,000 to Rs 25,000 per vote, and there are around 17,000 to 18,000 voters, so adding the cost … it came to around Rs 25 crore to Rs 30 crore. I decided not to contest, it was beyond me.”

Studies conducted by various independent research agencies have shown that the trend of “note for vote” has become extremely common in India and has been on the rise irrespective of the socio-economic status of the recipients. In fact, the earliest evidence of bribing voters goes all the way back to the mid-1950s when parties would offer meals to people and then later request them to vote in their favour.

It is also important to keep in mind that the amounts seized by the ECI, are just a drop in the bucket of the actual amounts of money in circulation during elections. While the election commission places limits on election spending of around Rs. 50–70 lakh for Lok Sabha election candidates, and around Rs. 20–28 lakh for each assembly candidate, the actual expenditures far exceed these limits.

While certainly not all of the expenditure of candidates goes into exchanging cash for votes, it is certainly a significant portion of the expenditure.

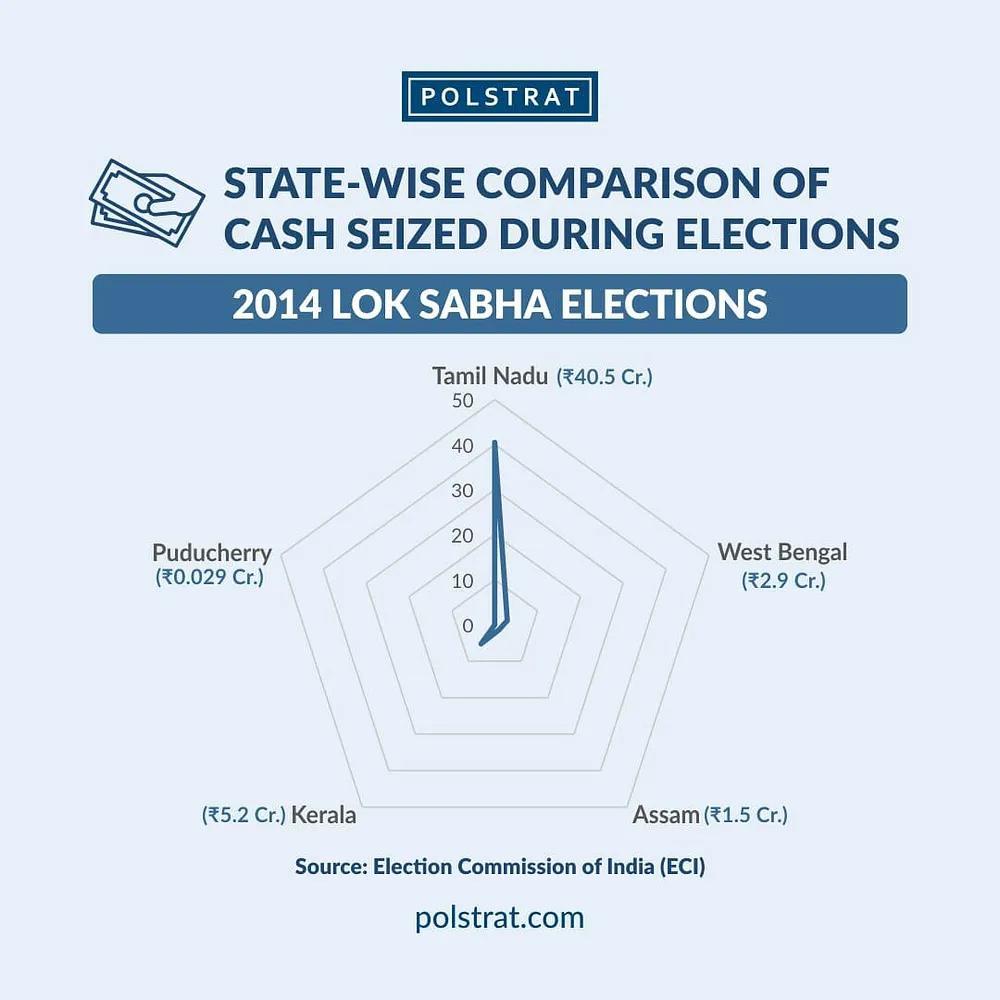

Even during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the ECI reported cumulative seizures of cash and freebies amounting to roughly Rs. 5,000 crores, while the overall estimated expenditure during elections was at around Rs. 55,000 crores (Centre for Media Studies). As per data available, 8,024 candidates participated in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Even if we take the upper limit of permitted spending per candidate it adds up to a total expenditure of around Rs. 6,639.22 crores. However, estimates suggest that all candidates themselves spent at least Rs. 24,000 crores in the elections.

Can an EVM really be hacked?

During any election in India — whether it is a bypoll, national or state elections, media reports with allegations of voter fraud through malfunctioning electronic voting machines (EVMs) or through the tampering of said EVMs undoubtedly do the rounds. Almost all political parties accuse each other of EVM tampering and orchestrating voter fraud. However, the question that now arises is whether EVMs really are that easy to tamper with and manipulate? The short answer is no, they are not.

EVMs can be hacked in two main ways: wireless and wired. As per the analysis by various cybercrime and election experts EVM hacking is an extremely complicated feat. As EVMs are not networked devices hacking any EVM would require altering the machine itself. This means that anyone attempting to hack an EVM can not do so remotely, and would need physical access to machines themselves, which would require them to be in collusion with EVM manufacturing authorities, the ECI as well as companies that make the chips in EVMs.

EVMs are currently only produced by two public sector units in India, and the engineers producing the EVMs would have no knowledge of where an EVM they have manufactured would be deployed.

Other allegations of EVM tampering also state that EVMs are transferred after votes have been polled without mandated security of the ECI. Parties allege that these could be attempts to swap out actual EVMs with other ones. However, as per the ECI, all EVMs are placed in strong rooms that are under surveillance 24 hours a day under CCTV cameras and in the presence of CAPF security. A lot of the EVMs which are shown as being transferred without adequate security are “reserved EVMs” which are kept in case of malfunction of other EVMs in circulation.

That being said, some cases of voter fraud have still been reported, such as during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, when polling agents stepped up to the balloting units and pressed the button for a voter. Additionally, due to some lax monitoring, some instances of EVMs being found outside politicians’ residences and unsafe godowns have also been reported in the past few elections.

However, these instances are rare and are usually prevented by ECI’s micro observers and polling agents of other parties. Usage of EVMs offers countless benefits such as verifiability, accuracy, security, secrecy and accessibility. EVMs ensure that no individual can revote, that every individual’s vote is recorded and counted accurately and that all votes once recorded can not be manipulated. Overall, it could be said that the majority of the reports of EVM tampering and malfunction are simply political rhetoric and are not feasible.

Hate Speech: Violation of the Electoral Model Code of Conduct

One of the first rules of the model code of conduct (MCC), as prescribed by the ECI, is that “no party or candidate shall include in any activity which may aggravate existing differences or create mutual hatred or cause tension between different castes and communities, religious or linguistic”. In simple words, it prohibits hate speech. In 2021 so far, the Election Commission has placed a ban on several candidates, including West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee and DMK leader A Raja for using communal and religious rhetoric in their speeches while campaigning.

It is no secret that elections in India are fueled by emphasising communal and religious identity. Hence, it is no surprise that parties use such rhetoric while campaigning to emphasise and re-establish community identity. You may ask: if this is such a commonplace practice, what is the ECI doing to curb the same? The ECI has launched a mobile application whereby any citizen can share proof of malpractice by political parties, candidates and activists when the MCC is in force. The information uploaded from the application is transferred to a control room, where field units or flying squads are alerted for further action.

However, the ECI has also highlighted that it has extremely limited powers in addressing the issue of violation of the MCC by candidates and parties through the usage of hate speech. In 2019, during the Lok Sabha elections, in response to a public interest litigation (PIL) filed the Supreme Court, called the commission “toothless” for failing to act against political leaders who made polarizing speeches.

The Supreme Court had made an inquiry into action being taken against leaders who had made polarizing speeches, to which the ECI replied that it does not have any powers by which it can disqualify a candidate for violating the rules of conduct. The counsel for the EC explained that in any case of the violation of the MCC, in the first instance, the candidate is issued a notice and a reply is sought. If the candidate does not respond, then an advisory is issued, after which the EC files a complaint.

Deep Bhattacharyya & Shreya Maskara /New Delhi

With inputs from Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Sehal Jain, Oshin Anna Shaji, Raunaq Sharma, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.