Extreme Heatwaves Raising Alarms in India

The original version of the article was published on 25th May 2022 in “The Daily Guardian”

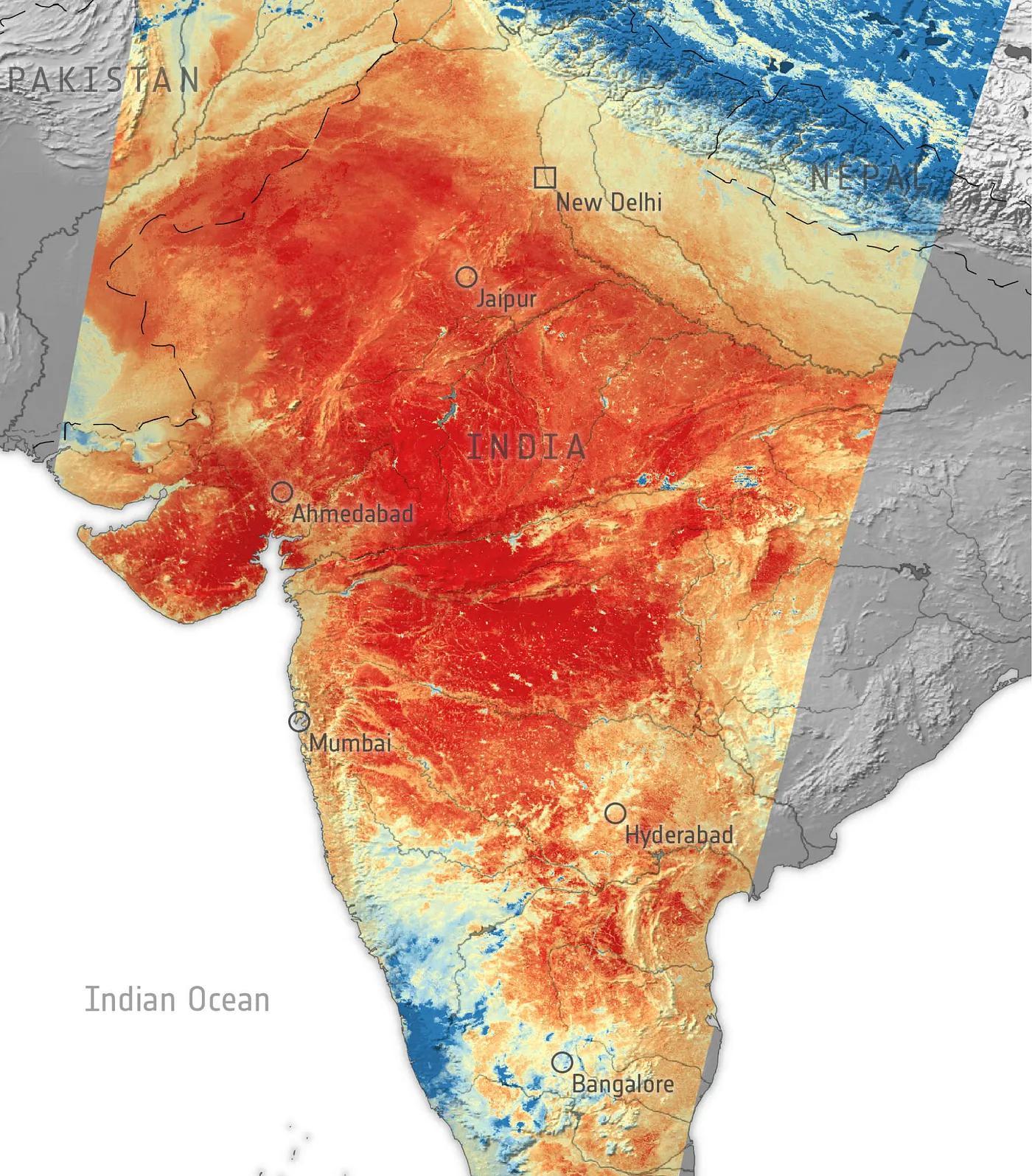

Large parts of India and its neighbouring countries, including Pakistan, have been experiencing record high temperatures as a heatwave continues to engulf the subcontinent. The heatwave began in early March and continues to aggravate millions across the country. Major cities, including the national capital, recorded temperatures as high as 49.2 Celsius, which is the highest in 122 years (since records began). Heat warnings and advisories have been issued in many cities and states, with many schools changing school timings to accommodate for the impact such severe weather could have on young children.

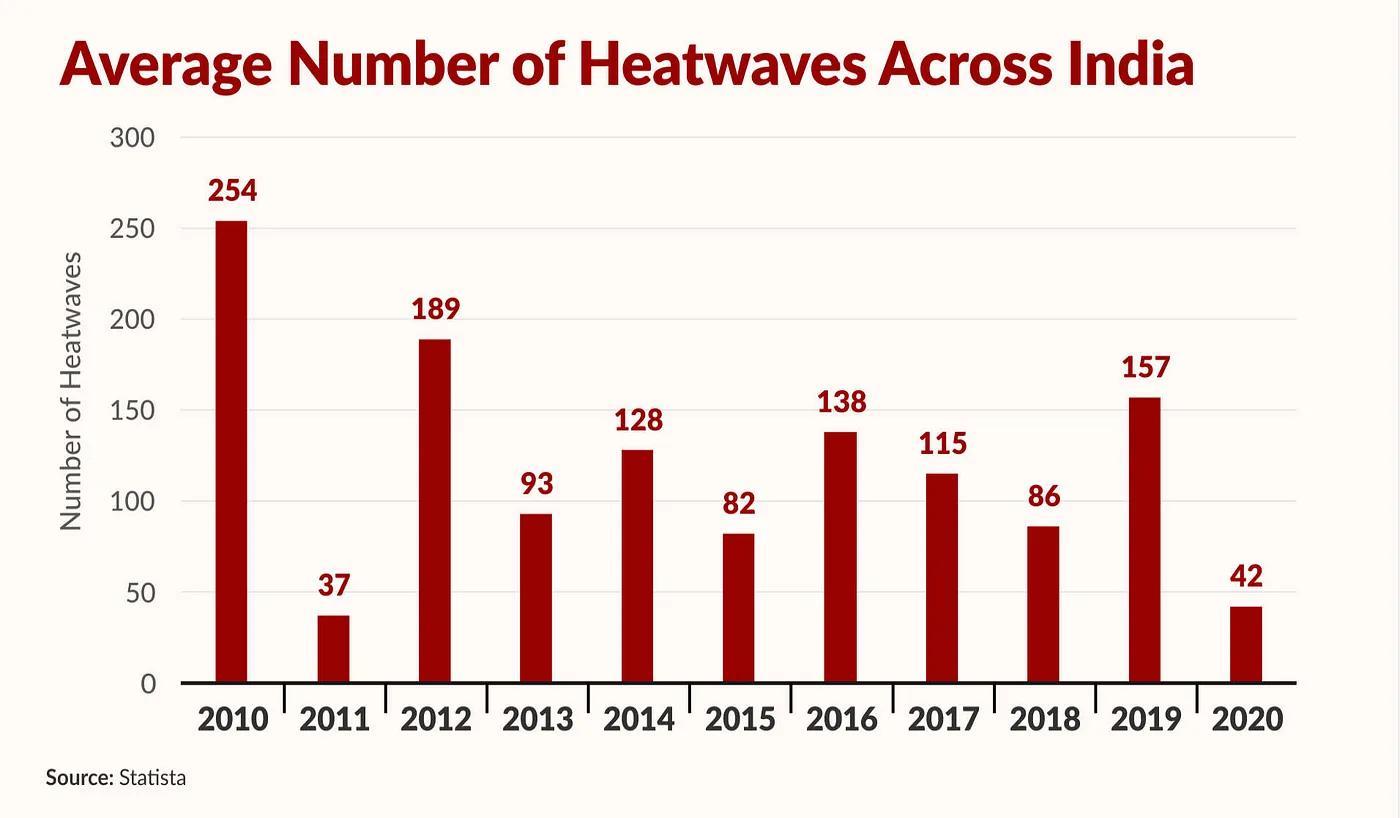

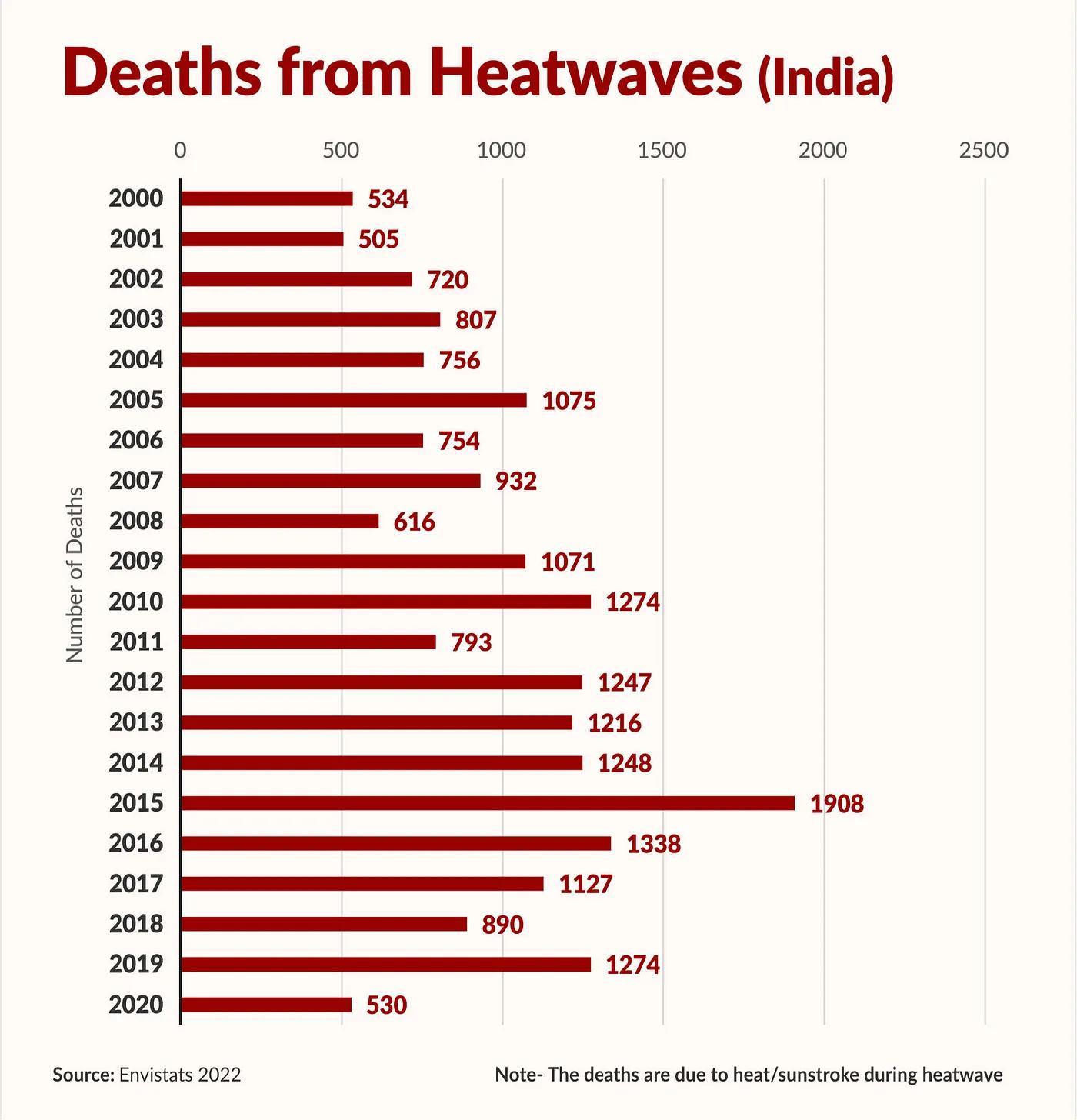

As per the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), a region is said to be experiencing a heatwave if maximum temperatures continue to exceed 40 Celsius in lowland regions, or at least 30 Celsius in the highlands, for at least two consecutive days. A heatwave is also declared if temperatures are 4.5–6.4 degrees above average, with temperatures 6.4 degrees above normal being classified as a “severe heatwave”. The heatwave has already claimed many lives across the country, apart from having a direct impact on the livelihood of those engaging in the informal economy and agricultural activities. The heatwave is also having an ecological impact, with reports in some cities of dehydrated birds falling from the sky. Additionally, it has exacerbated India’s power crisis, created by a short supply of coal and excess demand from industries. Amidst reports of the impact of the heatwave, studies produced by scientists at the World Weather Attribution initiative and the United Kingdom Met’s office revealed that extreme weather events such as the ongoing heatwave in India have been made more likely due to human-caused climate change, raising alarms across the globe.

What are the Key Findings of the Study?

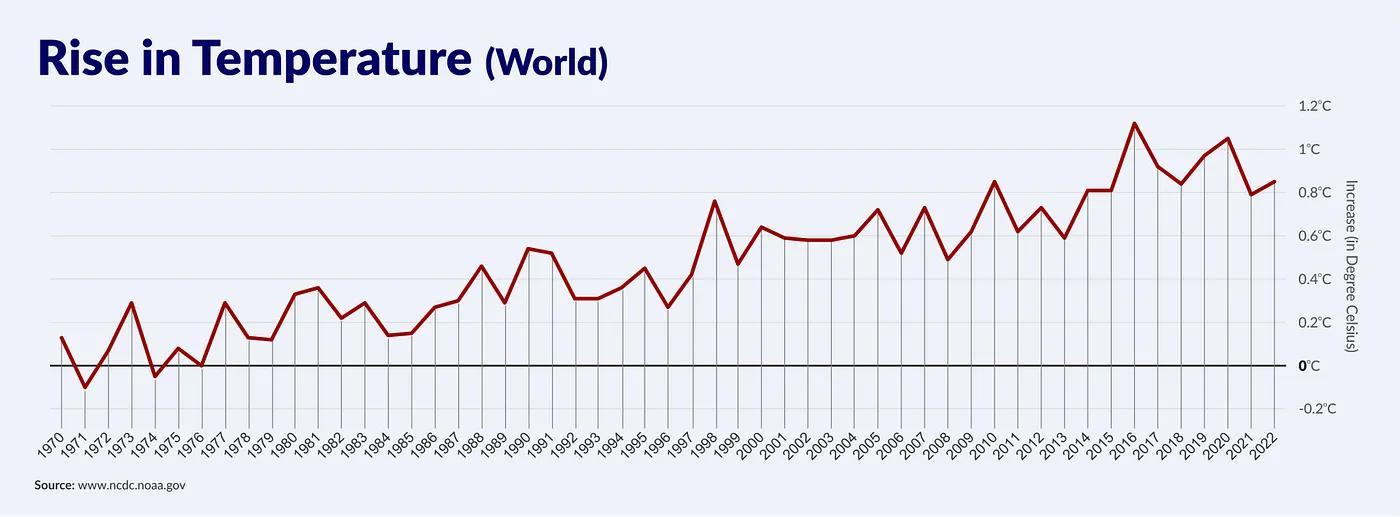

An international team of climate scientists at the World Weather Attribution initiative published a study last week examining the role of climate change in earlier extreme heatwaves in the Indian subcontinent. 29 researchers, as part of the World Weather Attribution group, including scientists from universities and meteorological agencies in India, Pakistan, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, participated in conducting the study. They analysed records of maximum daily temperatures in north-western India and south-eastern Pakistan to compare how they have changed with global temperature rise. The month of March this year was the hottest in India since records of the weather began 122 years ago. Pakistan also saw record high temperatures. In an attempt to quantify the changes in the weather, scientists analysed weather data using computer simulations, to compare the climate as it is today, after temperatures rising approximately 1.2 degrees because of global warming since the late 1800s, with the climate of the past.

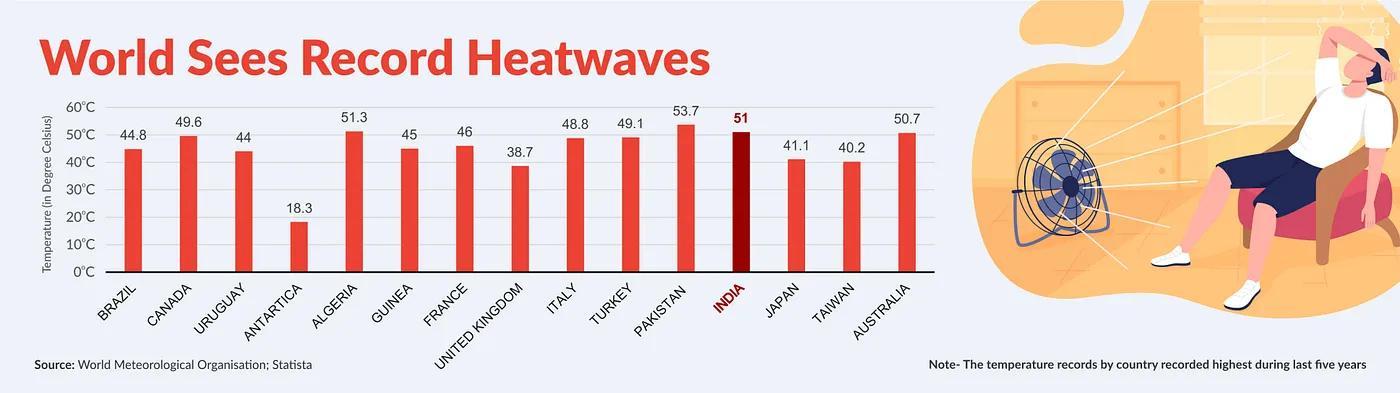

It was found out that at present the chances of such a heatwave happening are once every 100 years. However, in a world without climate change, such an event would only happen once every 3,000 years, implying that climate change has led to extreme weather events becoming 30 times more likely. The team also used the same climate models to make projections about how the probability of such events could change in the future. The results revealed that if the rise in global temperatures continues to be 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, such heatwaves could become two to 20 times more likely and could be up to 0.5 to 1.5 Celsius warmer.

In a similar manner, a group of scientists from the United Kingdom’s MET office also conducted a study, published earlier in May, which found that the record-breaking heatwave in India and Pakistan had been made 100 times more likely due to climate change. Scientists explained that the main reason for the difference in findings between the two studies was the different parameters used by the researchers. The Met office focused on a 2010 heatwave that affected different parts of India and Pakistan from May to June and instead imagined this heatwave had occurred in 2022. “Spells of heat have always been a feature of the region’s pre-monsoon climate during April and May,” said Scientist Nikolaos Christidis from the UK Met Office in a press release. “However, our study shows that climate change is driving the heat intensity of these spells making record-breaking temperatures 100 times more likely.” Both studies concluded that due to human-caused climate change, it’s now “common” to find such record-breaking heatwaves and that such “extreme weather events” are no longer “extreme” or “rare”.

How has the heatwave in the Indian Subcontinent Affected Life?

On 28 April this year, heat-related watches were in effect in almost all Indian states, covering millions of people and affecting all major cities. As per estimates, 90 people have already died in the subcontinent as a result of the heatwave this year. However, the real figure is likely to be much higher, as India counts ‘heatstroke deaths’ as only those deaths medically certified as having been caused by direct exposure to the sun, thereby capturing only 10 per cent of the real figure, leaving out deaths due to high ambient temperature. A major economic impact of a heatwave is on productivity and working hours for millions of people, especially those who work outdoors. According to an International Labour Organisation (ILO) report from 2019, India lost around 4.3 per cent of working hours due to heat stress in 1995 and is expected to lose 5.8 per cent of working hours in 2030. In absolute terms, India will lose the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs in 2030 as a result of heat stress.

For the Indian subcontinent, where a large cross-section of workers engages in either the informal economy or in agricultural production, intolerable heat has a dire impact on productivity as it reduces the hours available for workers to work outdoors. Chandni Singh, an environmental social scientist at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, said people working in informal settlements or those working in labour-intensive outdoor jobs are most affected. The heatwave also has an unequal impact on poor women, who are particularly vulnerable to heat stress as they tend to work inside homes without air conditioning. In rural parts of the country, women’s roles primarily include household work such as cooking and gathering provisions and water from outside their homes, all of which are labour intensive jobs. Daily wage workers, who work in construction not only bear the brunt of the heatwave, working extensively outdoors but also suffer greater heat exposure as they live in overcrowded spaces with little ventilation or air conditioning.

Due to the changes in average weather, overall living standards in India are expected to decline. A report by the World Bank titled “South Asia’s Hotspots — The Impact of Temperature and Precipitation Changes on Living Standards” showcased that when converted to GDP per capita, changes in average weather are predicted to reduce income in severe hotspots by 9.8 per cent in India by 2050.

The early onset of the heatwave impacts agricultural production, which is the primary source of income for millions in the country, especially those living in rural areas. As a result of the combination of the heatwave and the lack of rainfall, thousands of acres of agricultural produce and yield have been destroyed. As a result, the government announced a temporary ban on wheat exports, pushing up global prices further. As per an analysis published by the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), extreme temperature shocks reduce yields for kharif crop (sown in monsoon) by 4 per cent and for rabi crops (sown in winter) by 4.7 per cent.

Such extreme weather events also cause a rise in spontaneous combustion. In April in New Delhi, a rash of landfill fires was caused due to spontaneous combustion. While in general calls to fire departments typically increase this time of year, Atul Garg, director of fire services in New Delhi, said that this time, the numbers have been a lot more. Typically 60 to 70 calls are recorded per day during this time of year, and this year it has been up to 160 per day.

The National Disaster Management Act, 2005, and the National Policy on Disaster Management, 2009, do not include heat waves in their list of natural calamities. As a result, financial and infrastructural resources are also not diverted towards the problem. Around 100 cities and 23 state governments have partnered with the NDMA to develop Heat Action Plans (HAP) as adaptation measures for extreme heat events. However, these action plans and warning systems are not resilient or effective against heat waves as they are not recognised under the National Disaster Management Act, 2005, making them ineligible for money from national or state disaster response funds.

Alarm Bells Ring Again, but Will We Listen?

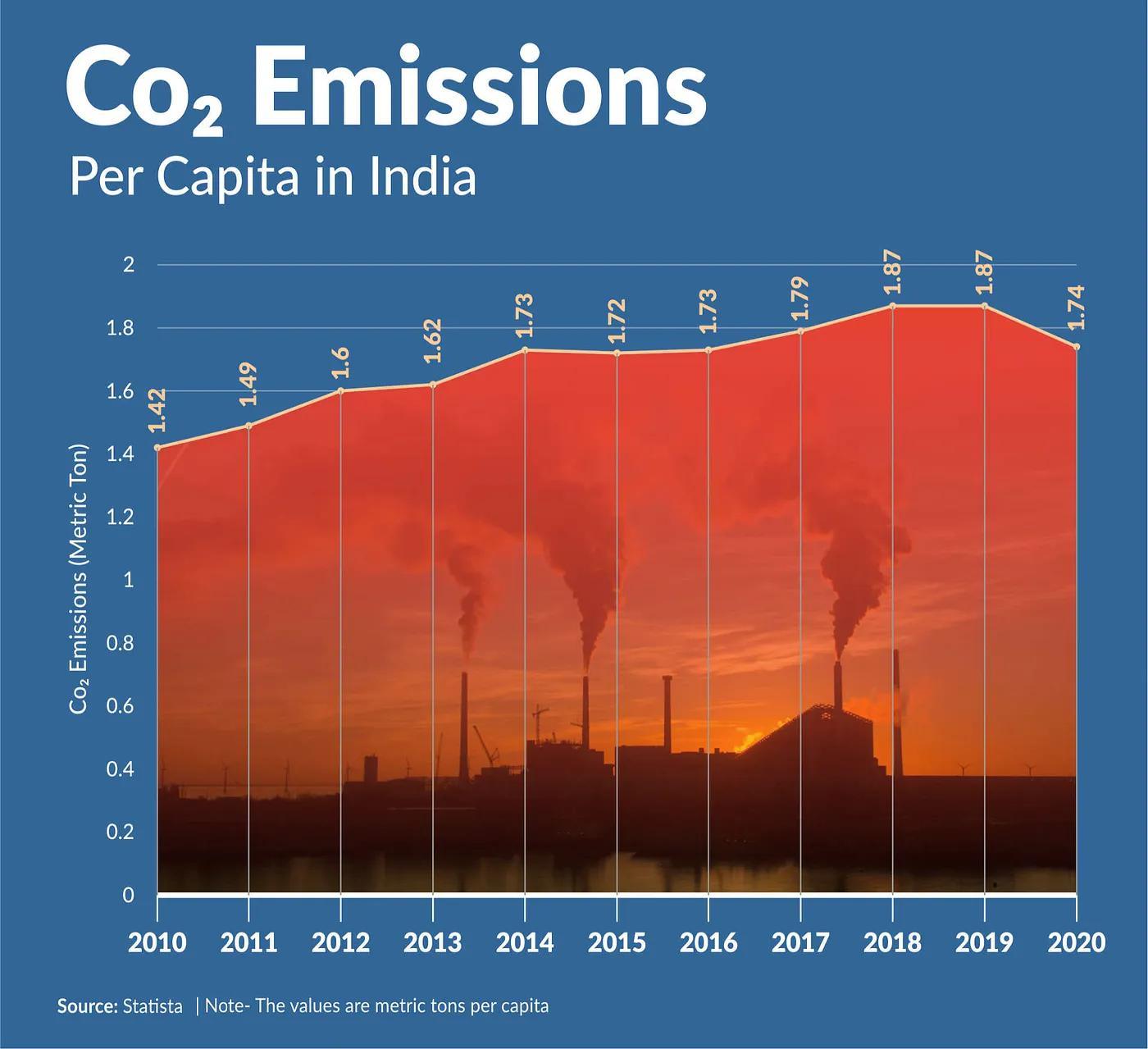

Undoubtedly, the scorching heatwaves in the Indian subcontinent have been enough cause for alarm that they have occupied national and international headlines for the past few days. Scientists, civic society organisations and environmentalists have pointed out that extreme temperatures are a sign of the direct impact of climate change and the lack of putting climate change friendly policies at the forefront of decision making. At the beginning of the COP26 conference on climate change in Glasgow in November last year, India announced that it aimed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070. It also announced ambitious targets for 2030, including quadrupling its clean energy capacity to 500 GW, sourcing 50 per cent of its electricity from renewables, and reducing the emissions intensity — the number of greenhouse gases released per unit of economic activity — by 45 per cent compared to the 2005 baseline. While India has added renewable energy at a faster clip than any other large country in the world, including an 11-fold increase in solar-generating capacity over the last five years, scientists argue that the country is not even close to playing catch-up when it comes to mitigating climate change.

State governments started to formulate targets to combat climate change by designing State Action plans prior to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which was signed in 2015. While some incremental steps are being taken by the state governments, these are nowhere near the scope or the scale required to contribute effectively to the national goal of carbon neutrality. Many states have realised the challenges in implementing these climate action plans, with the most prominent being the lack of climate finance along with limited scientific knowledge, and technical and institutional capacity constraints. The lack of coordination between institutions, departments, and stakeholders at various levels has also severely undermined collaborative climate action in the past. Action against climate change continues to be on the backburner for organisations and governments despite alarm bells.

Shreya Maskara/New Delhi

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Senior Research Associate at Polstrat and Kaustav Dass, Nehla Salil, Pavitra Mohan Singh, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.