How COVID-19 has affected Mid Day Meals in India’s schools

In India, mid-day meals in government schools are seen as a tool to provide not only quality education but also introduce intervening measures in nutrition and health.

A study published in June 2021 in Nature Communications, a scientific journal published by Nature Research, highlights the intergenerational benefits of mid-day meal schemes in improving the health standards of children in India. The study, authored by researchers from the University of Washington and the International Food Policy Research Institute, points to an improved height-to-age ratio in children of mothers who could access the mid-day meals (MDM) when they were attending school. The benefits of access to better nutrition on overall well-being and improved lifestyle are well documented. In many rural and backward areas, the provision of the mid-day meal scheme acts as an incentive for parents to send their children to school. It is known to be effective in reducing the financial burden on low-income households while also ensuring access to healthy and nutritious food for school-going children.

In India, mid-day meals in government schools are seen as a tool to provide not only quality education but also introduce intervening measures in nutrition and health. During the COVID-19 induced lockdowns, the mid-day meal scheme in most states was brought to a complete halt. The closure of schools and shift to the online mode of education not only affected the learning outcomes but also jeopardized the health and physical growth of children from underprivileged communities.

In the light of this development, it is important to analyze the impact of pandemic-induced closure on the role of the mid-day meal scheme in improving the health and nutrition of school-going children. It also calls for a closer look at the impact on long-term growth and development of society if children are not able to access quality food apart from quality education.

Malnutrition in India

A paper published in the International Journal for Equity in Health used National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-3 data to analyze the socio-economic inequality in childhood stunting at the state level. It found that, across states, children from poor socio-economic households faced a disproportionate burden of stunting, more so in urban areas. Moreover, it also found that states having a lower prevalence of chronic childhood malnutrition show a much higher burden among the poor. Several other studies also highlight the increasing gap between malnutrition in rich and poor households over the years.

Access to healthy and nutritious food in the formative years of a child has a positive impact on improving cognitive functioning and physical health in later years. In the case of poor and disadvantaged households, poor nutrition effectively leads to impaired learning in schooling years and reduced ability to engage in sustainable livelihood activities later on. All these effectively create a situation where intergenerational malnutrition and low education increase the gap between the rich and the poor and in many ways, urban and rural households as well.

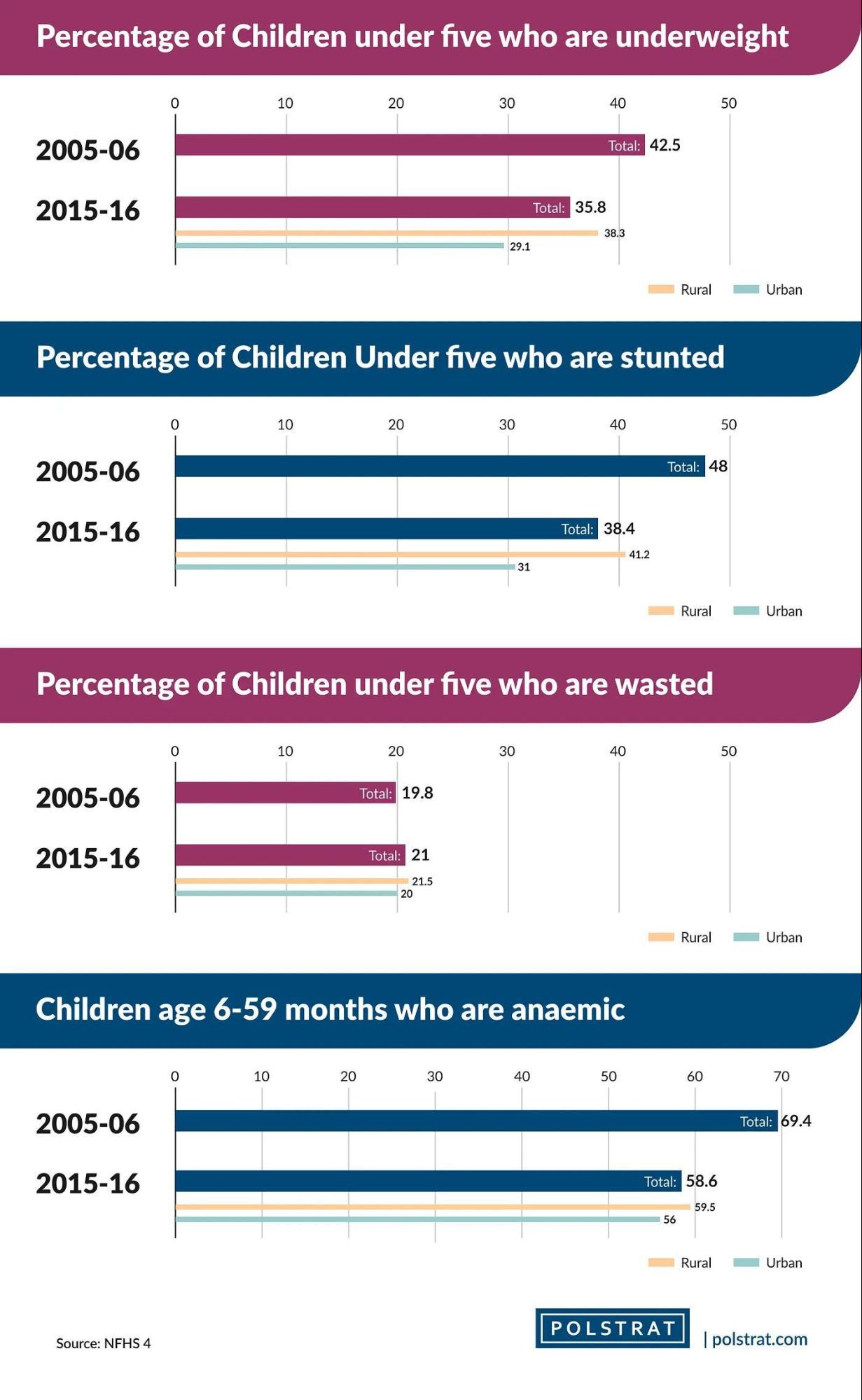

India has struggled with the problem of malnutrition since independence. While health indicators for children at all-India levels and individual states have improved over the years, recent figures paint a less than desirable picture of child malnutrition in India. According to the NFHS- 4 conducted in 2015–16, between 2005–06 and 2015–16, the proportion of stunted (low height-for-age) under-5 children has come down by nearly ten percentage points from 48% to 38.4%. While the improvement is significant, it also reveals the startling fact that more than 1/3rd of the children in India in 2015–16 had a low height for their age. Moreover, the gap between urban and rural areas was a further ten percentage points wide, with 31% of urban children and 41.2% of rural children under-5 stunted in 2015–16.

Under-5 wasted (low weight-for-height) children, another indicator of child malnutrition, barely changed as a percentage of the total population between the two years. From 19.8% in 2005–06, it increased marginally to 21% in 2015–16. For other metrics such as anaemia (iron deficiency in blood), the percentage of anaemic infants aged 6–59 months was as high as 69.4% in 2005–06 compared to 58.6% in 2015–16. The improvement in the metric seems insignificant when compared to the number of initiatives undertaken by various government agencies and the huge funds involved in improving maternal and child care in India.

The differences in access to resources not only at the household level but also between the ‘developed’ and ‘backward’ states of India exacerbates the problem of malnutrition and the above metrics bring to light only a small part of the problem.

Need for MDM and Impact on Long-term Growth

Healthy eating practices during childhood and schooling years are known to lead to better physical and mental capabilities in later life. Moreover, health problems owing to poor nutrition not only result in poor educational outcomes like low school enrolment, high absenteeism, early dropout, and unsatisfactory classroom performance but are also associated with high child mortality rates and higher incidence of non-communicable diseases in later stages of life. This calls for early intervention and preventive measures since childhood to ensure reduced incidence of diseases in later stages of life. The provision of mid-day meals in schools at primary and upper primary levels has been a game-changer in safeguarding nutritional needs.

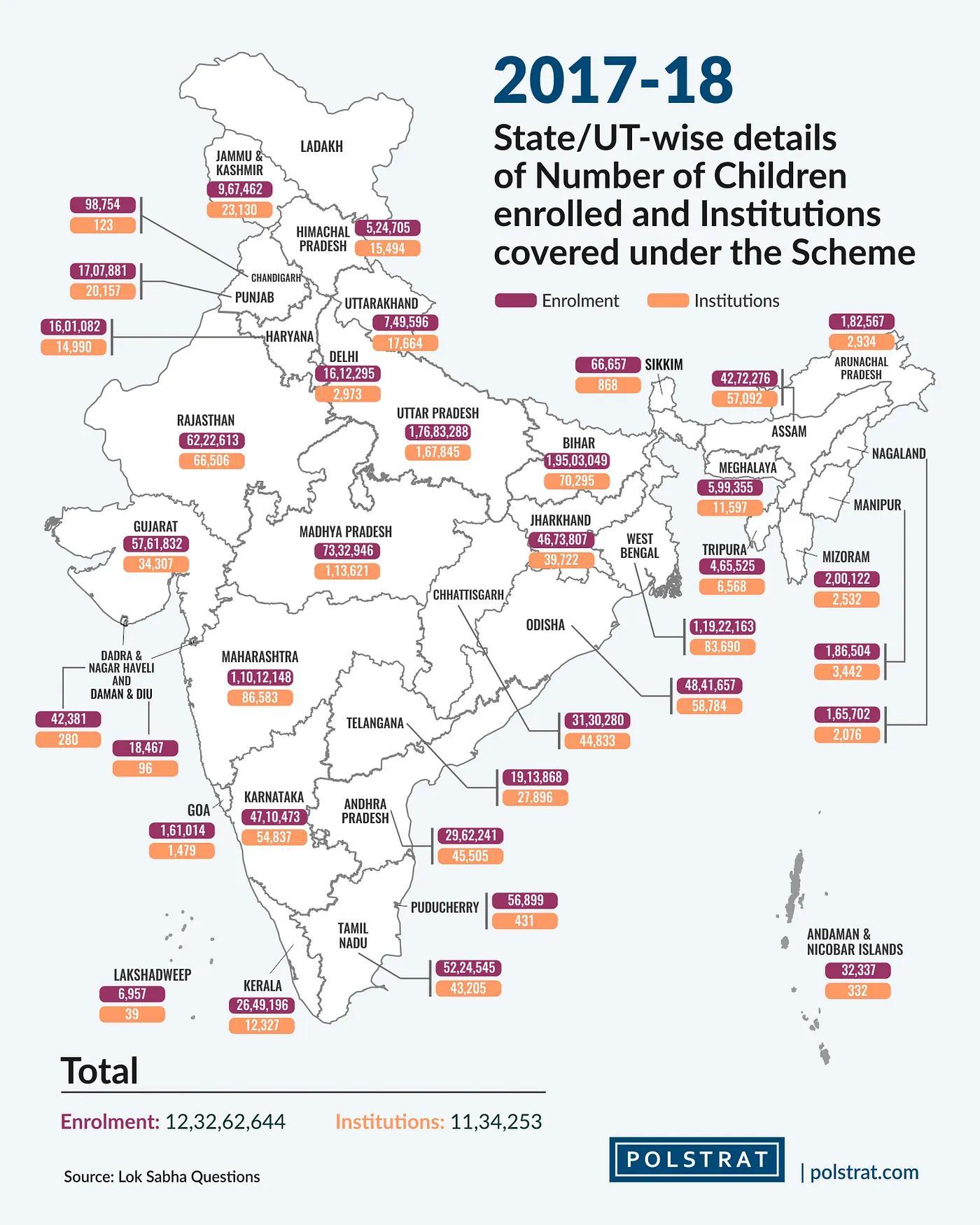

In 1925, the Madras Municipal Corporation for the first time provided cooked meals for school-going children in India. By the mid-1980s states such as Kerala, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and the Union Territory of Pondicherry universalized a cooked Mid-Day Meal Program for children studying at the primary level. In 1995, the Mid-Day Meal Scheme was implemented nationally with the launch of the National Program of Nutritional Support to Primary Education (NP-NSPE). The program aimed to enhance enrolment, improve attendance and quality of education, apart from improving nutritional levels among school-going children.

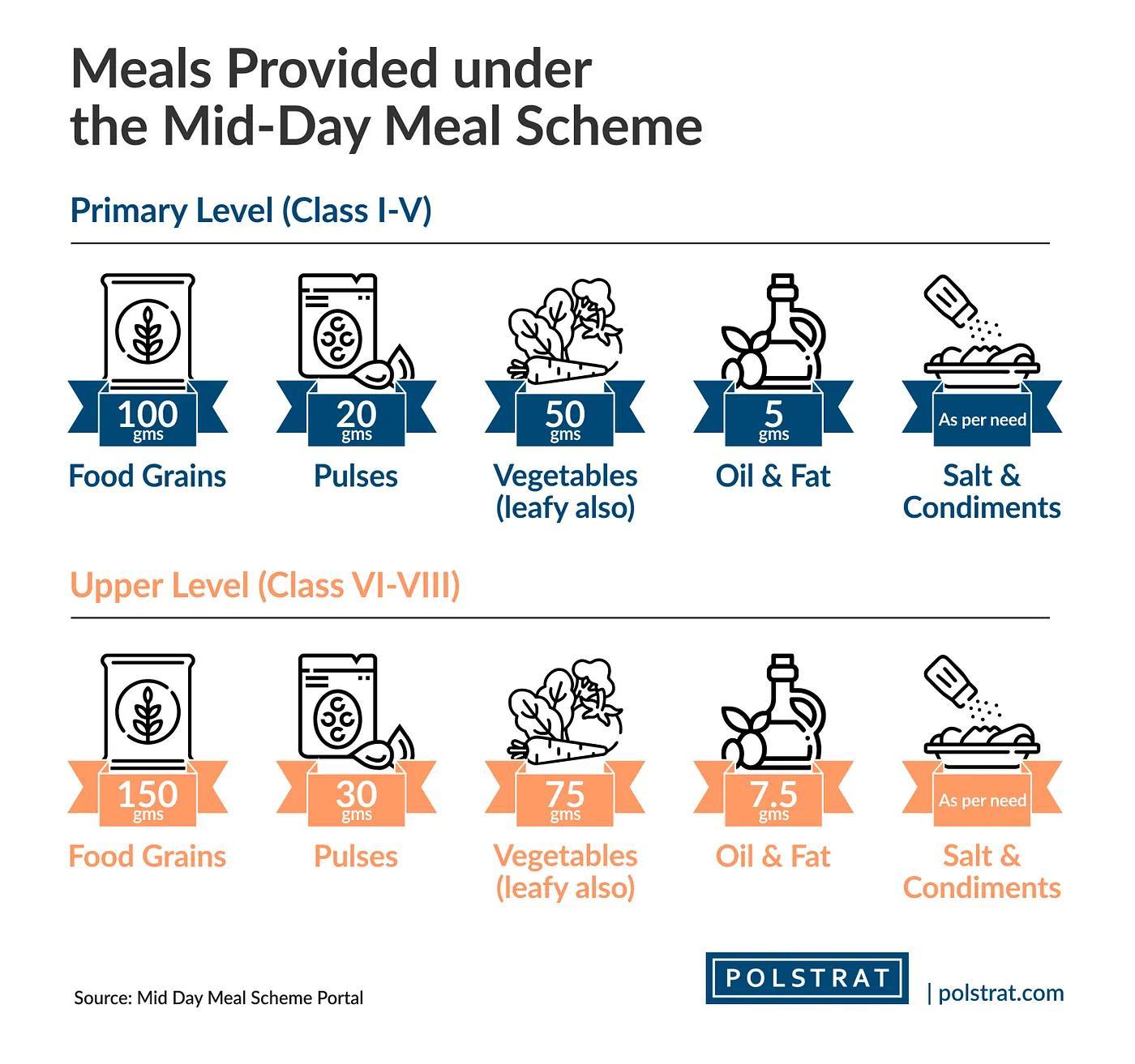

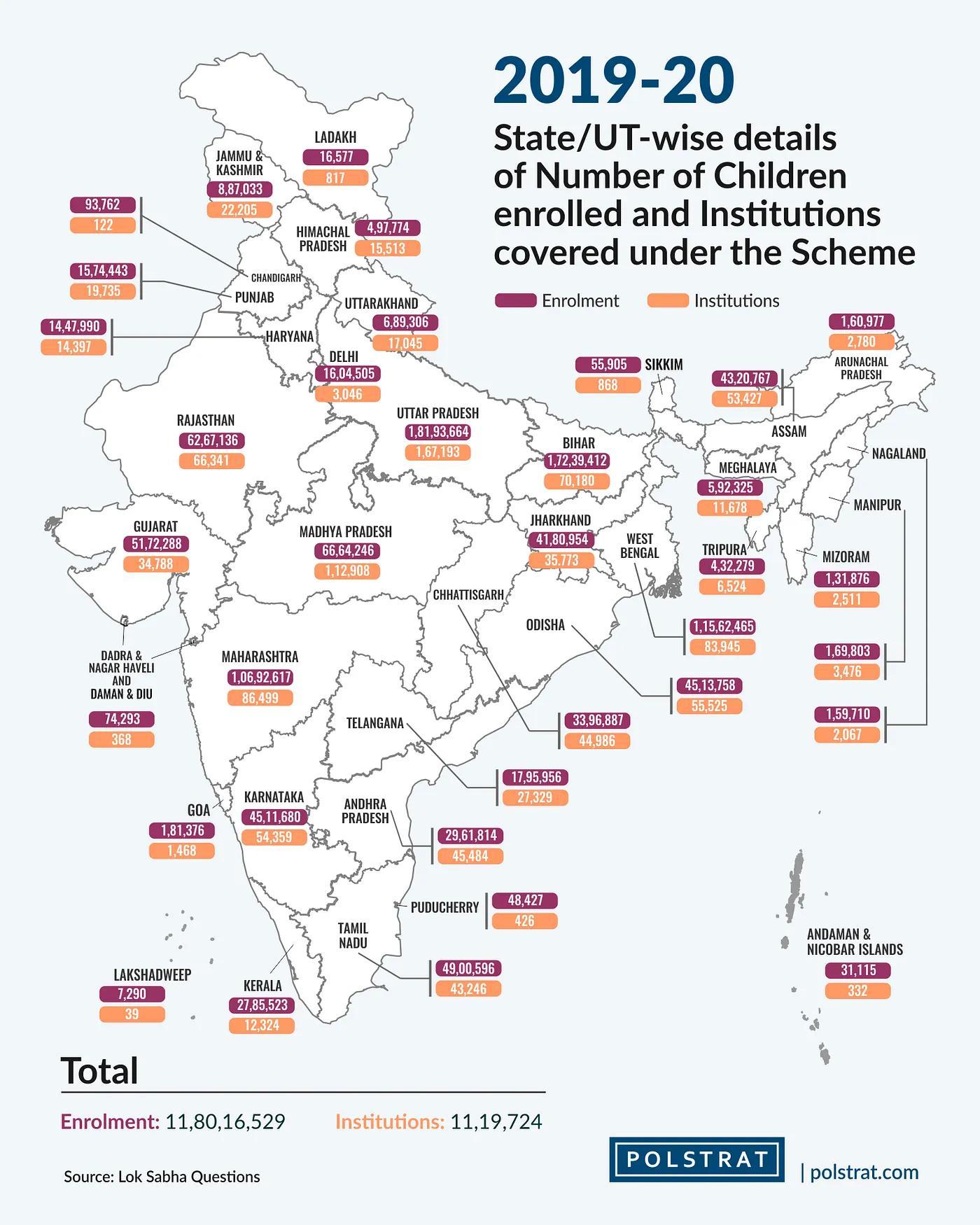

Since the implementation of the National Food Security Act 2013, the Mid-Day Meal scheme has become the world’s largest school meal program interlinked with attaining the goal of universalization of primary education. According to it, every child in the age group of six to fourteen years studying in classes I to VIII is to receive a hot cooked meal. To ensure that the meal has a good nutritional standard, the provisions of the scheme specify 450 calories and 12 gm of protein for primary (I- V class) and 700 calories and 20 gm protein for upper primary (VI-VIII class) students. Each meal is provided free of charge every day except on school holidays. While the actual nutritional composition of the meals provided is disputable and varies significantly from school to school, several attempts have been made to ensure that the quality and nutritional content of the meals are in line with the developmental needs of growing children.

In March 2020, as the nationwide lockdown began, the central government issued guidelines advising all states and UTs to provide hot cooked meals or food security allowance consisting of foodgrains and cooking costs, to all eligible children covered under MDMS. Other government schemes like POSHAN Abhiyaan (Nutrition Mission) and various stimulus packages like Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyan Yojana, and Garib Kalyan Anna Yojna also provided support. Moreover, Anganwadi centres/Nutrition Rehabilitation Centres (NRCs) across states were also directed to provide nutritious meals to children up to the age of six years and pregnant and lactating mothers.

State governments took several measures to provide dietary support in various forms. While Andhra Pradesh distributed dry rations to its beneficiaries, the Bihar government assured direct transfer of Rs. 358 and Rs. 536 to parents of primary and upper primary students to cover meal costs. Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra provided highly subsidized cooked meals to the urban poor through community kitchens.

According to experts, the distribution of dry ration does not take into consideration the reality that several of the poorer households do not have the facility to cook two square meals per day. Moreover, the disbursed amount was also seen as insufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of growing children, especially given the rising food prices during the pandemic.

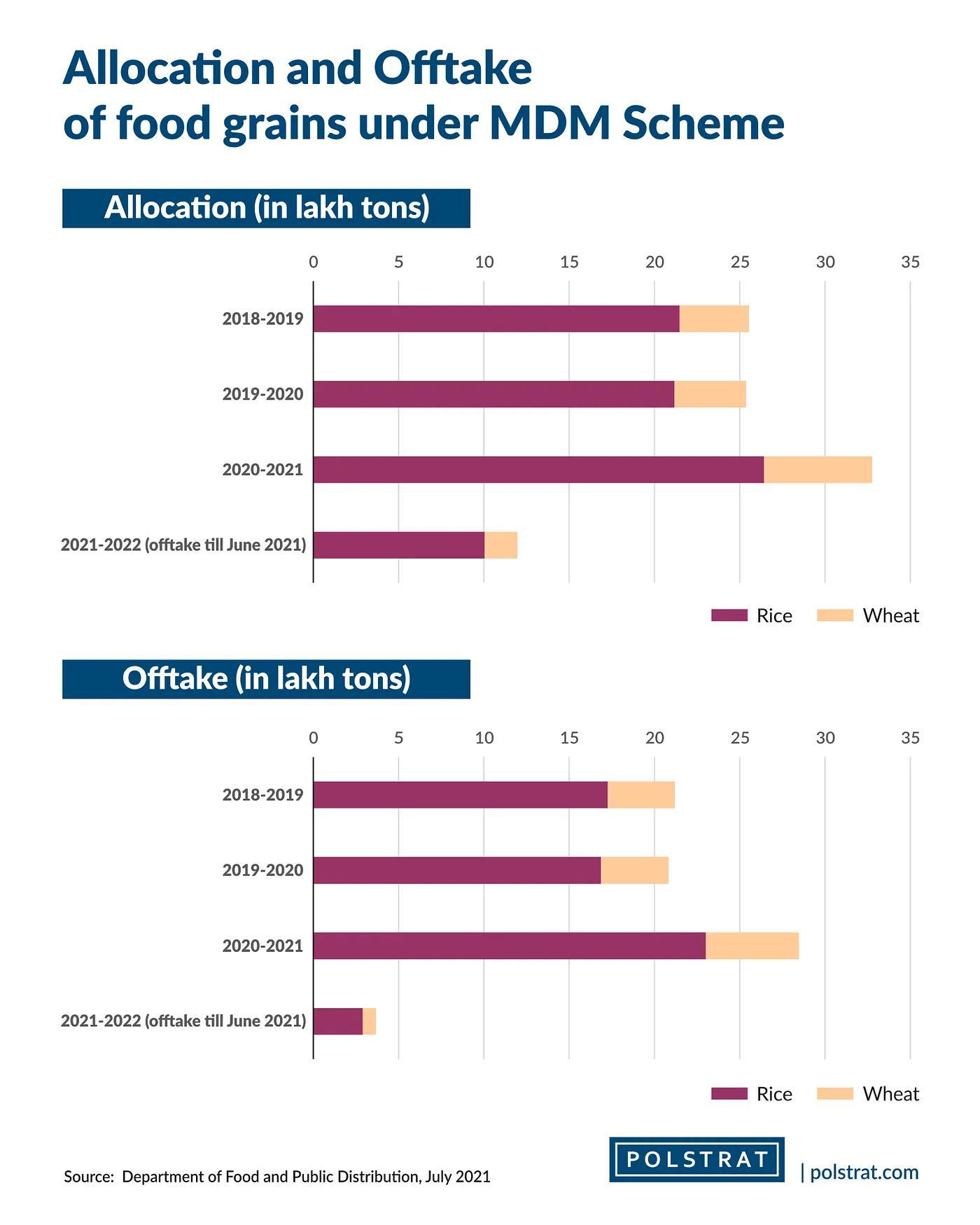

Data reveals that the impact of the lockdown on the implementation of the MDMS has been significant in spite of the several measures taken by state governments to provide nutritional support. In terms of allocating foodgrains from the central pool, 15 out of 36 states and UTs in India including larger states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha reported a decline in their offtake of foodgrains under MDMS in April and May 2020 compared to the same months in 2019. The total offtake by all states and Union territories (UTs) for April and May 2020 was 2,21,310 tonnes, 60,620 tonnes lower than the corresponding period in 2019.

In terms of an individual child’s access to meals, an assessment done by the Save the Children Foundation in 15 states found that around 40 percent of the eligible children did not receive mid-day meals during the 2020 lockdown. This is exacerbated by the fact that urban areas faced more difficulties in providing MDMs to children than rural areas. A strong ASHA and Anganwadi network in rural areas made it easier to reach the beneficiaries when the students were not coming to school. Moreover, in most states, lockdowns were more severely implemented in urban areas than in rural areas which further restricted the movement of any form of help.

Poor coordination between the central and state governments coupled with the diversion of resources to meet the health emergency needs further added to the problem. For instance, a Delhi government affidavit to the Delhi High Court in June 2020 said it was yet to receive funds from the centre for providing mid-day meals to children. The Centre, on the other hand, informed the Court that it had released over Rs. 27 crore to the AAP government as assistance under the mid-day meal (MDM) scheme.

What needs to be done?

Governments at the centre and the states have been providing low-cost dry ration and food grains to poor households through fair price shops and ration cards for many decades. However, the need to provide hot cooked meals in schools has birthed from the understanding that linking schools to the provision of meals will not only help achieve universal access to education but also contribute to dealing with malnutrition. Given the long term repercussions of poor nutrition pushing families back into poverty, state governments and local bodies need to continue with measures to provide dietary support to children even when schools are closed.

The steps taken by some states to provide cooked meals through community kitchens will augur well to continue nutrition support. For example, the Uttar Pradesh government’s decision to provide conversion money (cooking cost) apart from dry grains acts as additional support for low-income households. The actual impact, however, depends on the ability to plug loopholes in delivery and regular and timely payments. Adding pulses to the ration basket as was done by Haryana and Punjab, will help improve the nutritional content of the food. Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Karnataka governments’ decision to give additional items such as cooking oil, soyabean and pulses apart from foodgrains is another way in which the additional expenses of households for replacing MDM with home-cooked food can be shared by governments.

A healthy life ensured through access to quality and nutritious food is the bedrock of mental and physical development in the long run. It calls for the adoption of wide-ranging and innovative methods beyond the provision of dry ration or financial support. In the long run, the focus also needs to be on improving the nutritional composition of the food provided in any form. Measures to improve nutritional status need to target integrating efforts of different stakeholders- central and state governments, local bodies, NGOs, and the community. A decentralized bottom-up approach that takes into consideration the ground realities will go a long way in ensuring improved nutritional standards for children and later on adults.

Damini Mehta /New Delhi

With inputs from Akansha Makker, Animesh Gadre, Damayanti Niyogi, Kashish Babbar, and Kavya Sharma, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.