India Ranks Eighth on the Climate Change Performance Index

The original version of the article was published on 23rd November 2022 in “The Daily Guardian”

India improved its performance on the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) 2023, climbing up two spots to secure the eighth position out of the 63 countries in the index. This comes days after the country announced its roadmap to net zero emissions by 2070 during the United Nations Climate Change Conference, 2022 (COP27). The report also highlighted that while the country is on track to meet its 2030 emission target (compatible with -2 degree Celsius scenario), its renewable energy pathway is not on track. Let us take a closer look into the CCPI, how other countries performed on the same and what the road to 2030 and 2070 looks like for India.

What is the CCPI?

The CCPI tracks countries’ efforts to combat climate change and is an independent monitoring tool which aims to enhance transparency in international climate politics and enables comparison of climate protection efforts and progress made by individual countries. The CCPI report has been published every year since 2005 by three non-government organisations, namely the Germanwatch, New Climate Institute and the Climate Action Network. The report tracks the climate performance of 59 countries as well as all countries in the European Union, which overall account for 92% of all the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the world.

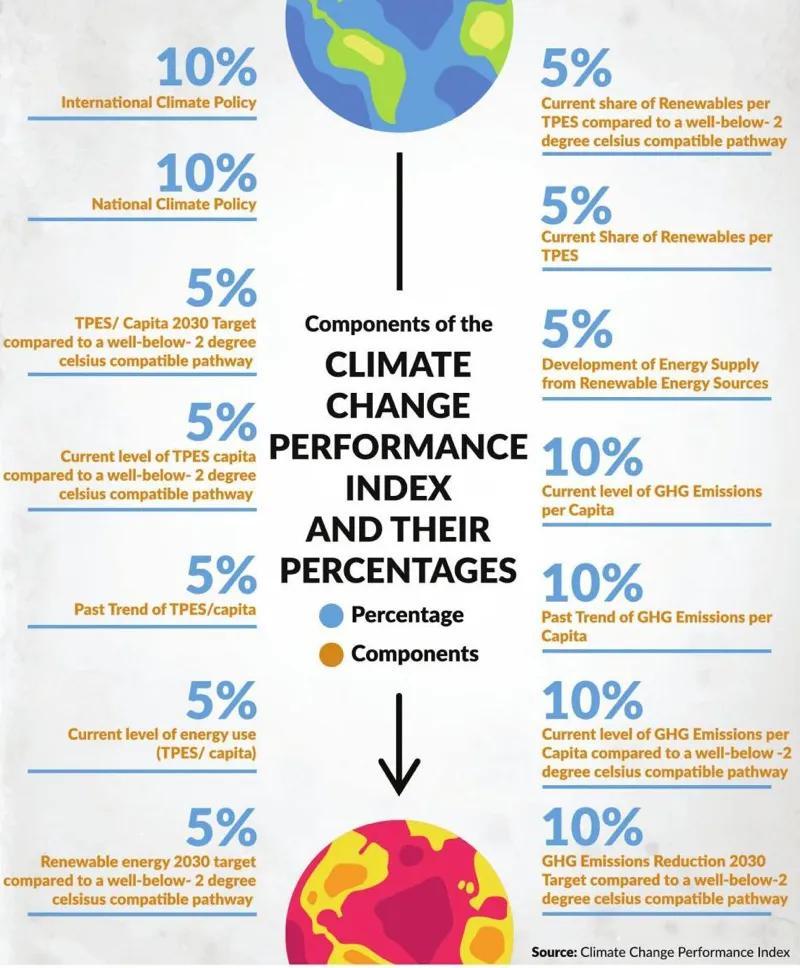

The rankings for the CCPI are based on standard criteria of 14 indicators across four major categories. These include renewable energy (which accounts for 20% of the overall score), greenhouse gas emissions (40%), climate change policy (20%), and energy use (20%). The assessment of any country’s performance is based majorly (80%) on qualitative data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), Paris Reality Check (PRIMAP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the national greenhouse gas inventories submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Due to data availability in the past, CCPI was calculated using data recorded two years prior to the year of the report (until 2022). However, CCPI 2023 uses GHG emission data for 2021 (in conjunction with numerical estimation and extrapolation) to avoid the effects of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic on emissions.

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges for the creation of a country-related composite index is the vast diversity of countries regarding geographical pre-conditions, historic responsibilities and economic capabilities. Calculating emissions is a great challenge for the CCPI, as the IEA data on energy-related emissions only includes emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. Direct emissions released in the process of conveyance are not accounted for.

What were the main findings of the 2023 report?

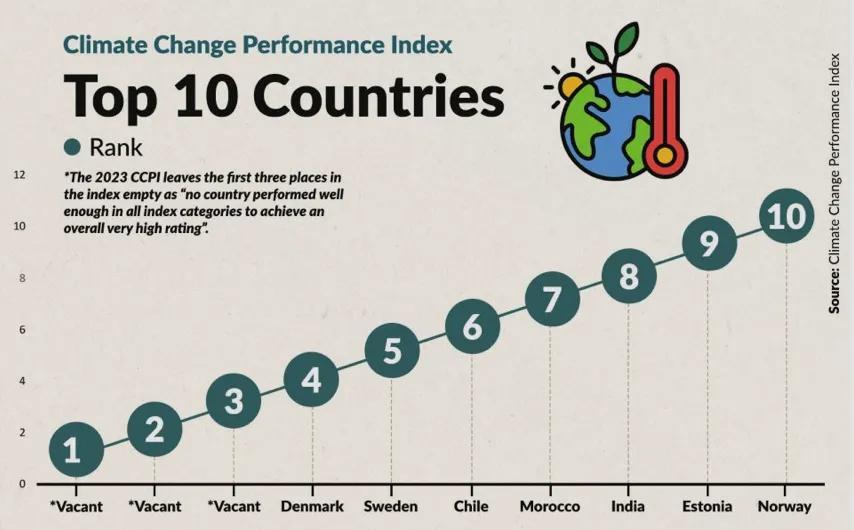

One of the main findings of the 2023 report is that the CCPI leaves the first three places in the index empty as “no country performed well enough in all index categories to achieve an overall very high rating”. Denmark placed at number four, followed by Sweden at number five and Chile at number six. Some of the key developments recorded in 2023 include that CO2 emissions rebounded in 2021, increasing by 6% and reaching a record high after a sharp 5.2 per cent drop in 2020. Despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, renewable energy capacities continue to expand at a high pace amidst the economic recovery from the pandemic. In 2021, 257 GW of capacity was installed globally, despite supply chain challenges.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent slowdown of economic activity led to a 4% decrease in energy demand in 2020. However, this demand was expected to rebound strongly in 2021, given the increase in economic activity. Global energy demand did rebound, increasing 4% in 2021, and returned to pre-pandemic levels.

However, due to the energy crisis which has resulted due to the Russia-Ukraine war, climate policy has faded into the background this year. For 2022, Australia is the only G20 country to increase the ambition of its National Determined Contribution (NDC). Brazil and India did not increase their targets with their new NDCs. The UN United in Science Report also states that the progress in NDC improvement is insufficient for keeping 1.5°C in reach.

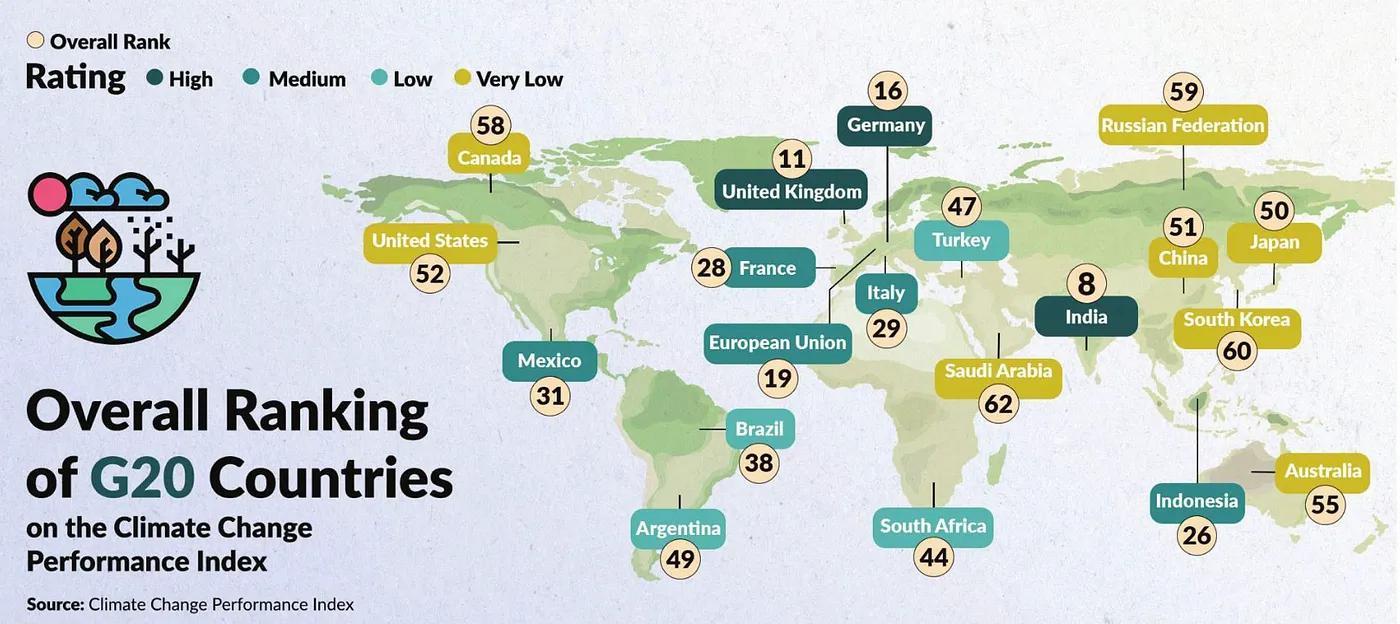

Overall, the countries that had the worst ranking were Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kazakhstan. All of these countries were ranked particularly poorly in renewable energy and are heavily reliant on oil as a source of energy. Chile, on the other hand, is one of the highest performing countries in this year’s CCPI, having moved up three ranks to sixth place. The country adopted a climate change framework law this year that includes a commitment to reach net-zero by 2050, including policies to implement this target. The country with the weakest performance in climate policy is Russia with the lowest score of 0.0. Turkey, Hungary and Brazil also performed very poorly in this category. In the category of renewable energy growth, Norway received a very high rating for the second year in a row. Countries that performed very poorly in this category were Algeria, Iran and Russia. Colombia, Egypt, and the Philippines are the three countries from the Global South which are leading the category of energy use. China is the largest emitter as per the report, having dropped 13 ranks in 2023, followed by the United States, which is the second largest emitter (ranked 52).

How did India perform?

As per CCPI 2023, India secured the eighth rank out of all 63 nations, while securing a “high” rating in the categories of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use. It also received a “medium” rating in the categories of climate policy and renewable energy. India’s rank on the CCPI has improved since 2021, where it placed on the tenth spot. This is majorly due to the fact that the country has made substantial progress towards its 2030 targets set during the Paris Climate Accords. These targets include cutting emissions by 45% to reduce global warming to 1.5 degree celsius. Overall, India placed ninth in the GHG emissions and energy use category, while it placed eighth in the climate policy category. Its worst performance was in the renewable energy category, where it secured the twenty-fourth spot. The report also highlighted that while the country is on track to meet its 2030 emission target (compatible with -2 degree Celsius scenario), its renewable energy pathway is not on track for the 2030 target.

India is the world’s fourth biggest emitter of carbon dioxide after China, the United States and the European Union. However, due to its huge population, its emissions per capita are often much lower than any other major world economies. India emitted 1.9 tonnes of CO2 per head of population in 2019, compared to 15.5 tonnes for the US and 12.5 tonnes for Russia that year. India has updated two of its five commitments made during the Paris Agreement to combat climate change, including reducing the emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% by 2030, as well as to get 50% of its electricity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. In 2021, during the Glasgow COP26 summit, the country also set a net zero target after years of rejecting calls for the same. Net zero, or becoming carbon neutral, means not adding to the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

According to a report released by former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd and others titled “Getting India Net Zero Report”, the country will require an economy-wide investment of $10.1 trillion from now to achieve its net zero emission target by 2070. India has been actively working on formulating a Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategies (LT-LEDS) paper, a climate action document that will spell out the country’s roadmap to net zero. This was formally released last week at the COP27 Climate Conference in Egypt, by Minister for Environment, Forest, and Climate Change Bhupender Yadav. The strategy calls for the investigation of a “significantly greater” role for nuclear power, which it claims is currently saving the country approximately 41 million tonnes of CO2 emissions annually and providing 3% of its electricity generation. India has accelerated the e-mobility transition by adopting electric and hybrid vehicle manufacturing schemes.

Another major challenge for the country is increasing the capacity of renewable energy. According to the CEA, India was meeting 9.2% of its electricity generation from renewables in 2019. By 2021, with an increase in renewable energy capacity to 102 GW, the generation had increased to roughly 12%. This needs to be increased to 50 per cent (500 GW) to meet the 2030 targets. Currently, roughly 60 GW of coal thermal power is under construction and in the pipeline. According to CEA, India’s coal capacity will be 266 GW by 2030, and the country has stated that it will not invest in coal production beyond this capacity. The Indian government has rolled out a range of policy instruments to support the development and deployment of renewable energy technologies and energy savings, including a Green Hydrogen Policy and an amendment to the National Energy Conservation Act of 2001.

Shreya Maskara/New Delhi

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.