Indian Households Crumbling Under Retail Inflation

Note: The original version of the article was published on June 23rd 2021 in “The Daily Guardian”

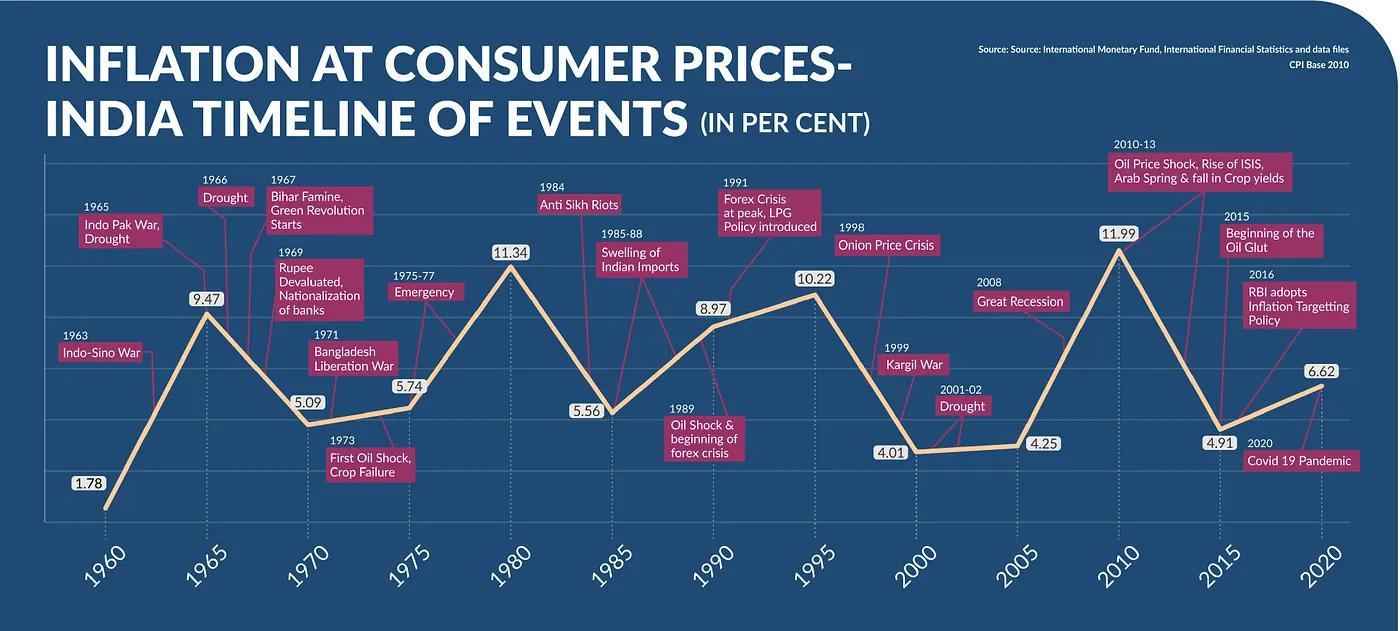

Managing inflation has been a herculean task globally during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. Global value chains are more connected than ever, and the change in prices of goods and services in one country has an impact in several parts of the world. Countries employ various tools ranging from monetary policy to fiscal spending to rein in inflation, which has a direct impact on the lives, livelihoods, and living standards of their populations. India was reeling under rising inflation even before the pandemic began, with food and fuel inflation being the major drivers of price rise.

Pandemic-induced lockdowns have further impacted economic activity negatively. Lower economic activity coupled with supply chain bottlenecks, domestically and internationally, have restricted the government’s ability to deal with inflation as physical and financial resources are diverted towards managing the Covid-19 situation. With this article, we hope to shed light on the constant rise in inflation during the various waves of the Covid-19 pandemic in India, the impact this has on individuals and businesses, as well as the measures being taken by the Government of India and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to control the same.

Food and Fuel Inflation: Individuals and Business Suffer

Note: The original version of the article was published on June 23rd 2021 in “The Daily Guardian”

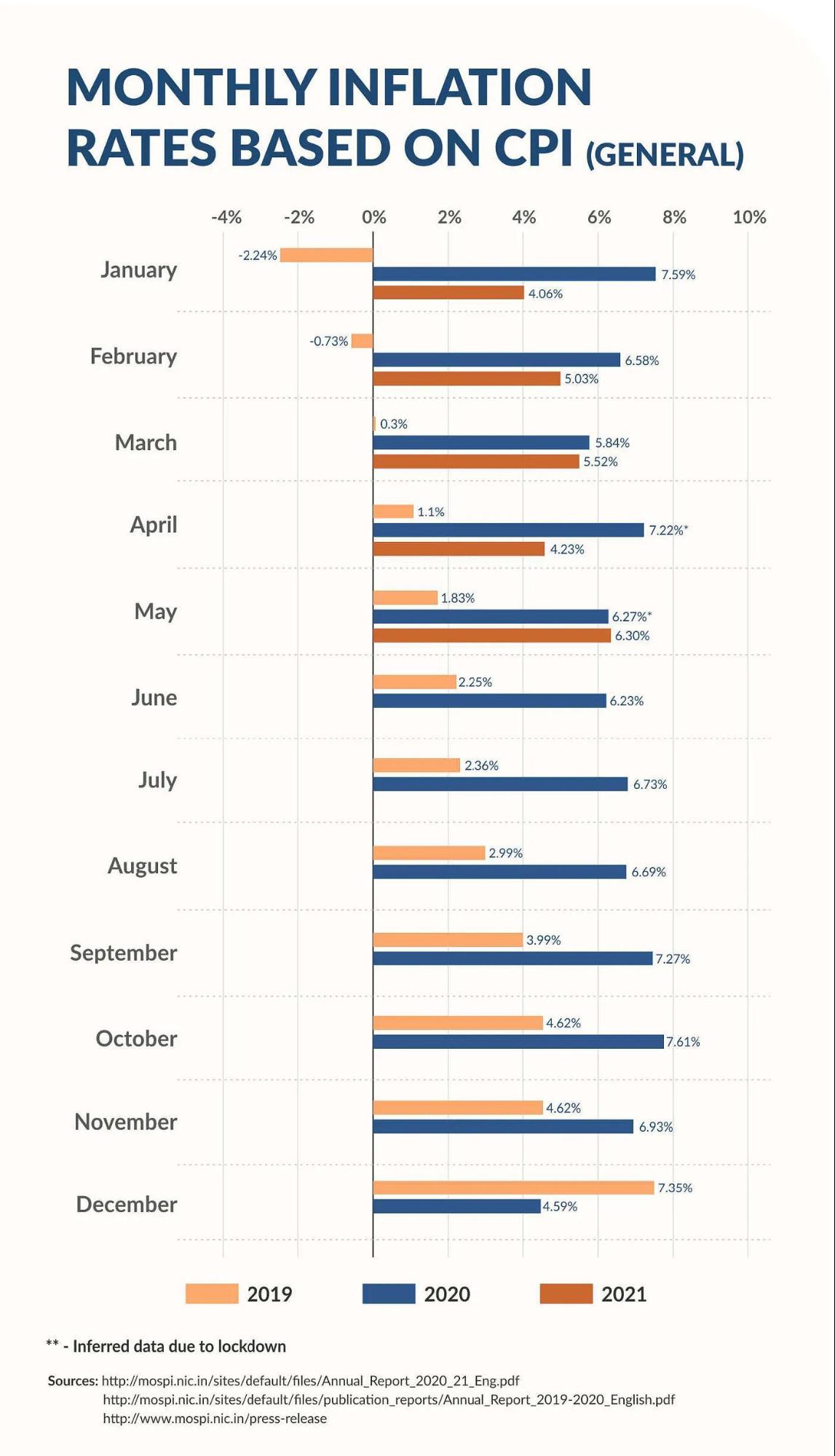

Business and economy sections of newspapers during the Covid-19 pandemic have featured similar headlines every day, mostly related to prices of commodities, including raw materials and consumer goods, which continue to rise, along with unemployment levels, while economic growth is spiralling to record lows. In May 2021, Wholesale Price Index-based inflation rose to a record high of 12.94 per cent, pushed by higher fuel and commodity prices while retail inflation touched a high of 6.3 per cent in the same month. As Covid-19 cases in India reduce after a devastating second wave, inflation continues to haunt Indian households, as prices of all commodities increase.

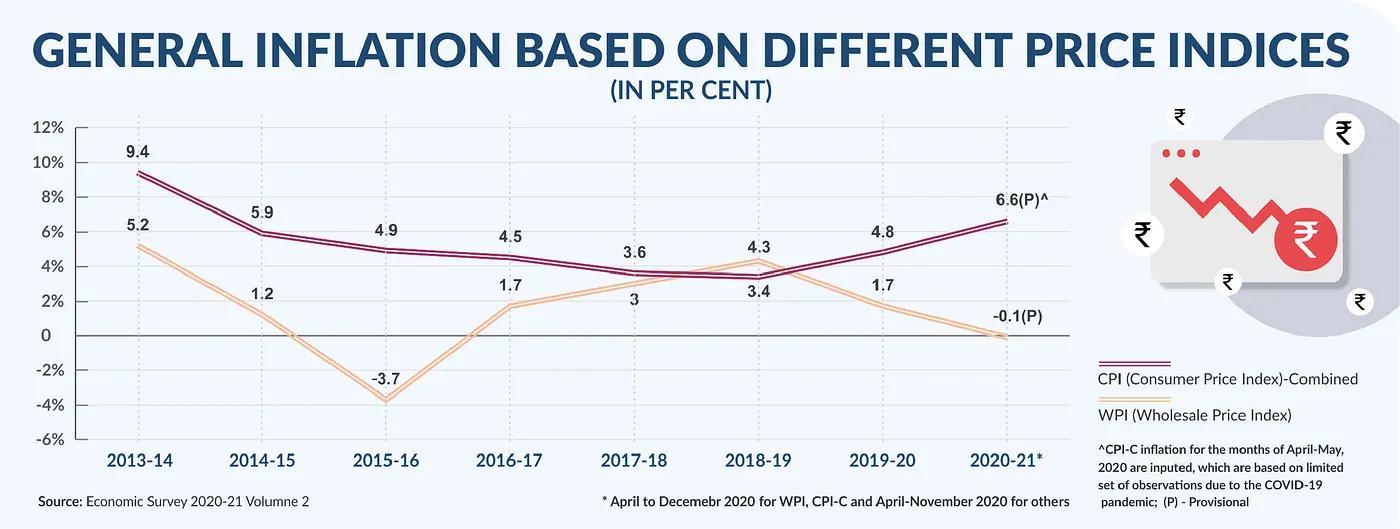

Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services bought by a typical consumer over a year. It is a macroeconomic indicator that measures inflation and monitors changes in the cost of living. A healthy CPI is critical to maintaining money supply and ensuring price stability in India.

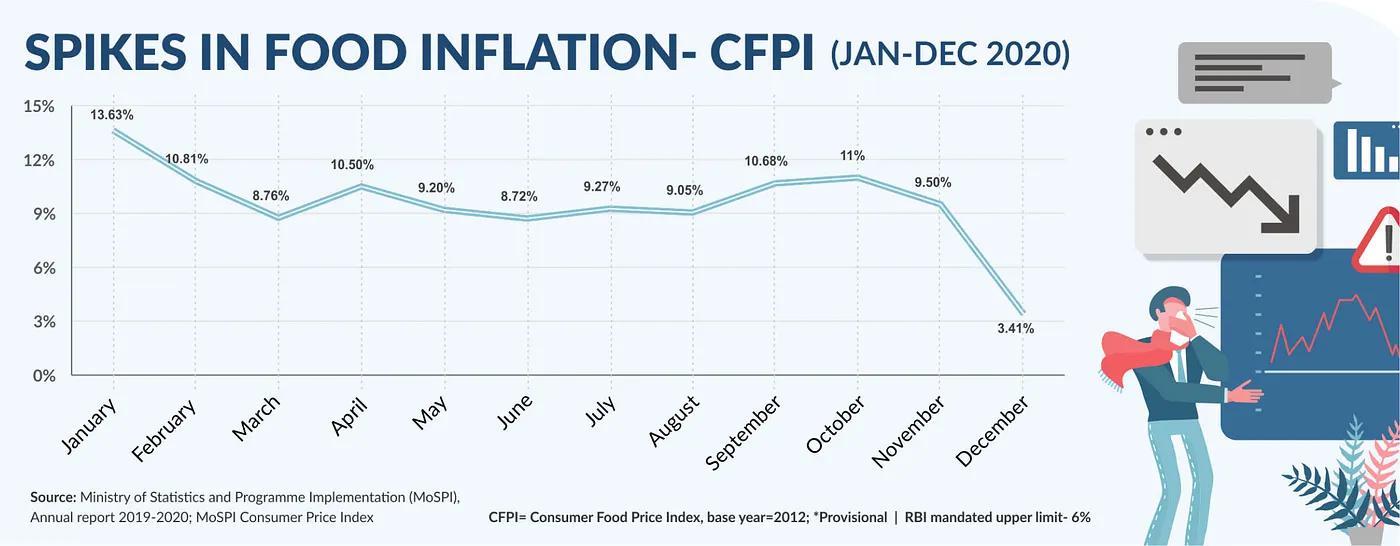

The rise in retail inflation across the country is directly proportional to a rise in food inflation. During the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, after the sudden announcement of a national lockdown, the agricultural supply chain across the country was severely disrupted. This caused a sharp rise in food inflation. The pandemic, which has already negatively affected the economy by pushing unemployment to an all-time high of 7.11 per cent in 2020 (Centre for Economic Data and Analysis, CEDA) and has resulted in lower incomes, is now threatening to increase malnutrition and nutritional poverty by pushing millions of people to lower their expenditure on food.

Food inflation hit a high of 13.63 per cent in December 2020 and reduced marginally to 8.76 per cent in March 2021. However, since the onslaught of the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, food inflation in the country has been much higher than the RBI’s mandated 6 per cent upper limit, while economic growth in the country touches record lows with every economic prediction. Economists state that a sustained rise in food prices will continue to have a worrying impact on India’s most vulnerable, putting pressure on their savings.

Other items in the basket that have pushed retail inflation include fuel, which recorded an inflation rate of 11.6 per cent in May 2021, transport and communications, which was recorded at 12.6 per cent, and edible oil at 30.8 per cent. In October 2020, the CPI hit 7.6 per cent, the highest it has been in 6.5 years due to rising gold prices, healthcare costs, and people’s increased preference for using private transportation due to Covid-19. The government’s policy of increasing taxes on fuels, which causes cost-push inflation in an economy, was a major factor behind the rise in the CPI. Additionally, the global rise in prices of edible oils is another major risk to the rising inflation baskets.

During the second wave of the pandemic, markets overall saw fewer supply chain disruptions, but the global rise in prices, along with an increase in prices of crude oil, gold, and edible oil, all of which are spilling over into consumer inflation, along with rising prices of food items are painting a very worrisome picture of the Indian economy. The surge in prices is not expected to stabilise anytime soon, as the RBI estimates CPI inflation at 5.1 per cent for the 2021–2022 financial year. It has predicted an inflation rate of 5.4 per cent for the second quarter, 4.7 per cent in the third quarter, and 5.3 per cent in the fourth quarter.

Why is the WPI Rising?

The Wholesale Price Index (WPI), measures the changes in the prices of goods sold and traded in bulk by wholesale businesses to other businesses. Before 2014, the WPI was given more weightage as an indicator of inflation by the RBI. However, in 2014, CPI was adopted as the official indicator to measure the rate of inflation in the country. The WPI rose to a record high of 12.94 per cent in May 2021 — this was the highest wholesale inflation rate since December 1998. Three major components that can be attributed to this record-high increase in the WPI are fuel, power, and manufacturing. Fuel and power have registered an increase of 37.6 per cent, followed by manufacturing at 10.8 per cent and primary article at 9.6 per cent. Manufactured products have a weightage of around 65 per cent in the WPI. This, compounded with a steep increase in prices of metals, rubber, chemicals, and textiles, has prompted a further increase in the WPI.

Economists suggest that globally rising prices of crude oil and essential commodities worldwide will continue to push WPI inflation further in India in the next few months. High taxes on retail fuel cause a spike in inflation and the transportation cost of the manufactured products has also increased, thus adding to wholesale inflation.

Monetary vs Fiscal Policy: What is the Solution?

The RBI faced many competing objectives on inflation, bond yields, and the rupee, in 2020 while struggling to encourage economic development when the economy was devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, since the second wave of the pandemic hit the country in March 2021, the job of the RBI became even more difficult, as it continues to struggle to maintain its objectives.

Governments often use fiscal policies, including changing tax and spending levels to influence the level of aggregate demand in an economy, thereby reducing the inflationary pressure on an economy. The 2021–22 Union Budget allotted INR 34.83 lakh crore for expenditure, which is roughly 15.6 per cent of GDP. In the recent past, no union budget has exceeded the limit of 13.5 per cent. Capital expenditure in the economy also received a huge boost to INR 5.5 crore. Additionally, the government reduced import duties on edible oil and masoor dal. However, in December 2020, the Ministry of Finance said that the government could not spend more because it was concerned about a higher fiscal deficit, and cut spending by about 22 per cent in the September quarter of the last financial year.

One of the major reasons an increase in retail inflation, especially food inflation is worrying for any economy, is that it often coincides with a contraction of demand in an economy. Rising food prices, when not compensated with an increase in food support from the government, force low-income households to dip into their savings, which are already falling due to the economic pressure of the pandemic. This is likely to cause a decline in overall household savings, jeopardizing any chances of recovery for a struggling economy. Economists have criticized the government for not increasing spending to compensate for the losses of households with low-income and those below the poverty line. While food inflation continued to be high even months after the COVID-19 lockdown, the government did not continue its free grain distribution scheme under the Pradhan Mantri Gareeb Kalyan Anna Yojana beyond November 2020.

India is certainly not the only country facing inflationary pressures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazil, which has been facing historically high inflation rates, has increased interest rates. The United States of America has also increased its interest rates to curb inflation which is at its highest levels since August 2008, when the recession hit. China is also seeing inflationary pressures in its economy due to an increase in prices of raw materials, and the Chinese government has decided to release its stockpiles of metals to reduce the pressure.

During its monetary policy meeting earlier in June, all eyes were on the RBI, with hopes that they would intervene to reduce the price pressure on businesses and individuals alike. However, during this meeting, the RBI announced that it would keep interest rates unchanged at current low levels, in an attempt to encourage growth in the economy. Economists state that the RBI needs to carefully forge a balance between fiscal and monetary policies in order to facilitate economic recovery in the country. Given the conflicting and competing objectives of the economy, this is undoubtedly easier said than done.

Deep Bhattacharyya & Shreya Maskara /New Delhi

With inputs from Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.