Lakhimpur Violence Impact on BJP Image in UP

Note: The original version of the article was published on October 13th in “The Daily Guardian”

On 3 October 2021, the visuals of a convoy of vehicles running over protesting farmers in the Lakhimpur Kheri district of Uttar Pradesh were plastered over mobile phones and television screens. Eight people, including four farmers, died in the ensuing violence which was intended to be a protest to block UP deputy chief minister Keshav Prasad Maurya’s visit to Banbirpur village. The protest was part of the farmers’ agitation that has been going on in several areas of the country for over a year, with farmers from different states unhappy with the three new farm laws passed by the Central government. Shortly after the incident, more protests by farmers’ organizations and opposition parties erupted across the country, demanding the arrest of Ashish Mishra, the son of Union Minister of State Ajay Mishra, who was allegedly driving the car involved in the incident. Police arrested Ashish Mishra on 9 October.

Potential Fallout as a result of Lakhimpur Violence

The arrest of Mishra, and two other accused, has not silenced opposition parties and farmer groups. The delay in arresting the accused and overall investigation by the Uttar Pradesh government has been criticized by the Supreme Court and the general public. The Yogi Adityanath-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, which is already facing a lot of backlash from farmer communities, is in hot water due to the involvement of Mishra’s son, who used to be an office-bearer in the BJP’s Lakhimpur Kheri unit. The ripples of the incident are likely to be felt in the upcoming Assembly polls in the state, as opposition parties are unlikely to brush it under the carpet.

The ramifications of the violence in Lakhimpur Kheri are likely to be paramount for the government in UP. The district is one of the largest in the Terai region of UP and has eight Assembly segments, all of which were won by the BJP in the 2017 Assembly elections. In 2012, the party had only won one seat out of eight in the region. The party had managed to significantly increase its vote share across all the eight assembly segments in the region in 2017, securing a vote share increase of roughly 40% in Palia AC, 45% in Gola Gorakarannath AC, 30% in Dhaurahra AC and 38% in Kasta AC. Dominant communities in the region include Sikhs, Brahmins, Kurmis and Muslims.

The agitation in UP had been confined to western UP to a large extent. The farm unions’ mobilization in UP is concentrated in western UP as sugarcane farmers in the region are unionized. In other farming dominant areas of UP, including Bundelkhand, Awadh, and eastern UP, farmers are not unionized to the same extent. With the Lakhimpur incident, the farmers’ agitation has penetrated deeper into Central UP and could have spillover effects in adjoining districts such as Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Hardoi, Sitapur, and Bahraich, where the party had recorded major victories in the 2017 elections by winning 37 seats of the 42 across the six districts.

Another important political ramification of the fallout is going to be the spotlight on MoS Ajay Mishra, who is a Member of Parliament (MP) from Kheri, and is considered a prime Brahmin face for the BJP in the state. Mishra, along with Jitin Prasada, was inducted into the Union Council of Ministers in July this year, in an attempt to reach out to the Brahmin community in the state. Brahmins have traditionally been strong supporters of the BJP — but lately, they have reportedly been expressing discontent with the Yogi Adityanath administration. Brahmin leaders have expressed feeling an “anti-Brahmin” sentiment amongst the ranks of BJP leaders, who they allege have been giving preferential treatment to Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Dalits at the cost of the Brahmin community. Brahmins in the state are angry at what they see as atrocities against them going unpunished in the Vikas Dubey encounter case and murder of journalist Vikram Joshi. This brewing discontentment among Brahmin groups is unlikely to completely shift the vote bank to opposition parties, but it could, however, impact the electoral prospects of the BJP in the state.

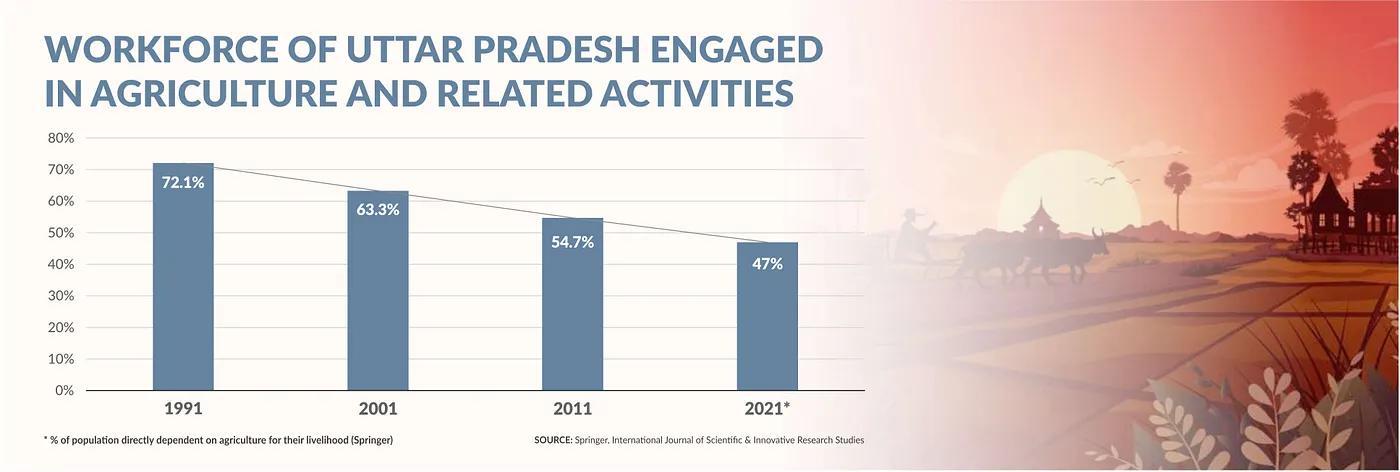

Farmers and the BJP: A Long Strained Relationship

Over the past year, tens of thousands of farmers from the country have camped on major highways at the borders of the national capital region of Delhi to oppose the farm laws, in India’s longest-running farmers’ protest against the government. Farmers have been protesting against the three agricultural acts passed by the Indian Parliament, which would allow them to sell produce at places other than Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC)-regulated mandis, enter into contract farming, and stock food articles freely. Protesting farmers believe the move towards greater privatisation in food markets is a ploy by the government to relinquish its responsibility of being the guarantor of minimum support prices (MSPs). MSPs work in the formally regulated APMC mandis, and not in private deals. Traditional farmers are afraid of the entrance of “big companies” into farming markets and feel the new laws will leave them vulnerable to corporate exploitation.

In November 2020, farmers’ groups led by the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) held sit-in protests across several districts of western Uttar Pradesh, blocking highways in support of the farmers of Haryana and Punjab, who marched towards New Delhi. Most of the farmers’ protests had so far been in western UP, which is the major agricultural belt of the state. Similarly, other western UP districts including Baghpat, Muzaffarnagar, Meerut, Bijnor, Hapur, Shamli, Bulandshahr, Ghaziabad, Noida, Moradabad, and Saharanpur also witnessed sit-in protests by the farmers. In September 2021, more than 5,00,000 UP farmers gathered in Muzaffarnagar to form the biggest rally against the BJP-led central government demanding the repeal of the three farm laws.

The political scenario in western UP has dramatically turned against the BJP since the farmers’ protests erupted — leaders of farmers’ organizations such as the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM), BKU (Bharatiya Kisan Union), and AIKS (All India Kisan Sabha) have collectively maintained that the BJP regime is “anti-farmer” for bringing in the three contentious farm laws. The Jat community in UP, dominant in the western part of the state, had shifted allegiance to the BJP in the past few elections. However, many have now turned against the party because they believe that the BJP is not willing to take back the farm acts which they have been protesting against for the past several months. The opposition parties, including the Indian National Congress and Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), have adopted the strategy of attempting to win over the aggrieved farmers’ votes by consolidating their anger against the ruling BJP. They have organized a series of mahapanchayats, to continue to brew the simmering discontent against the BJP. The only major opposition party in UP which has not been vocal about the farmers’ protests is the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP).

While the INC has been organizing mahapanchyats and protests against the BJP government, political analysts state that due to the lack of prominent faces in the state, the efforts by the Congress will not necessarily convert into votes and that the Samajwadi Party (SP) and RLD are likely to be the biggest beneficiaries of the anger towards BJP. SP leader Akhilesh Yadav has explicitly supported the farmers’ protests and called for the three acts to be repealed. He has also announced the repeal of the three farm laws as one of the key campaign promises for farmers for the upcoming Assembly polls. The RLD, with the active participation of former MP Jayant Choudhury, has also seen a resurgence in the state since the farmers’ agitation began. According to political analysts, the coming together of Akhilesh Yadav and Jayant Chaudhary could impact the political fortunes of the BJP in the state.

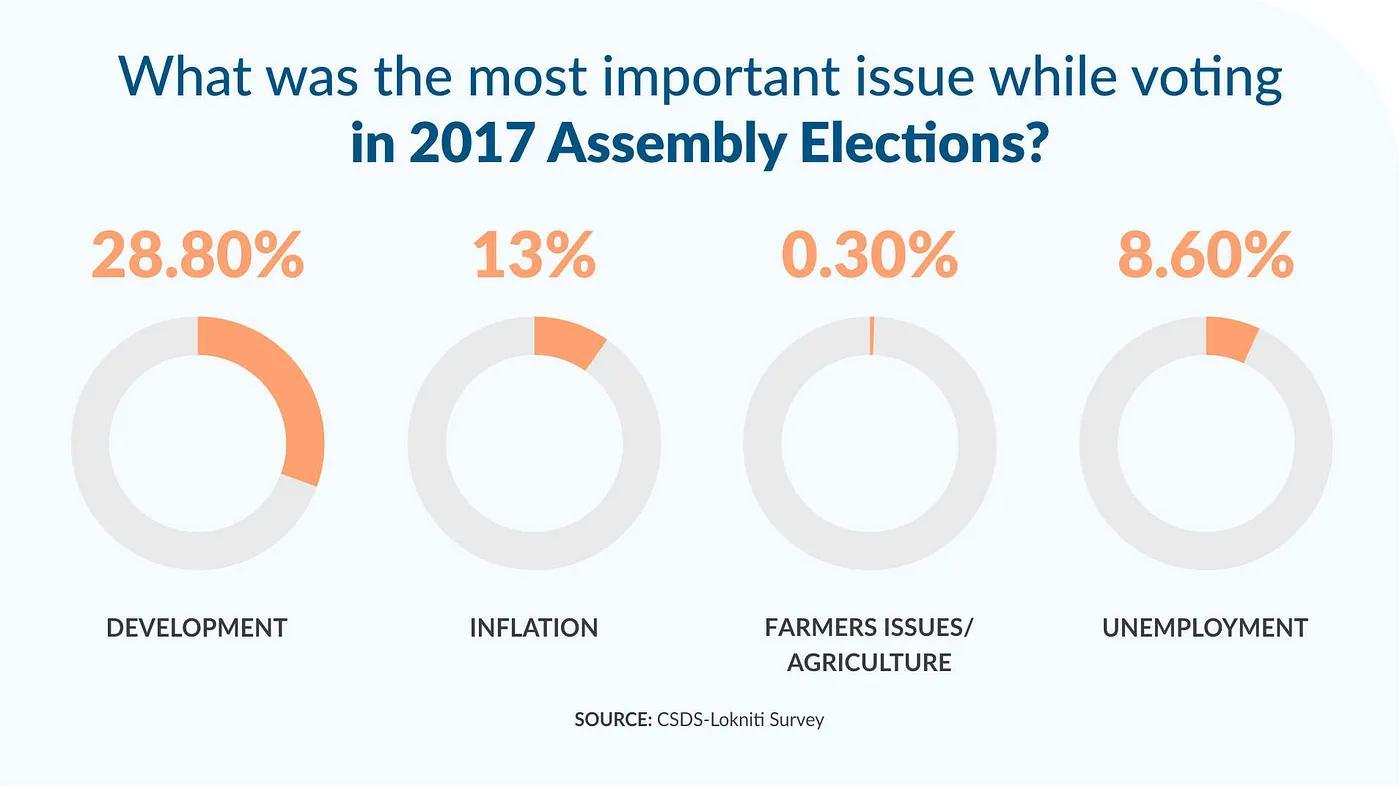

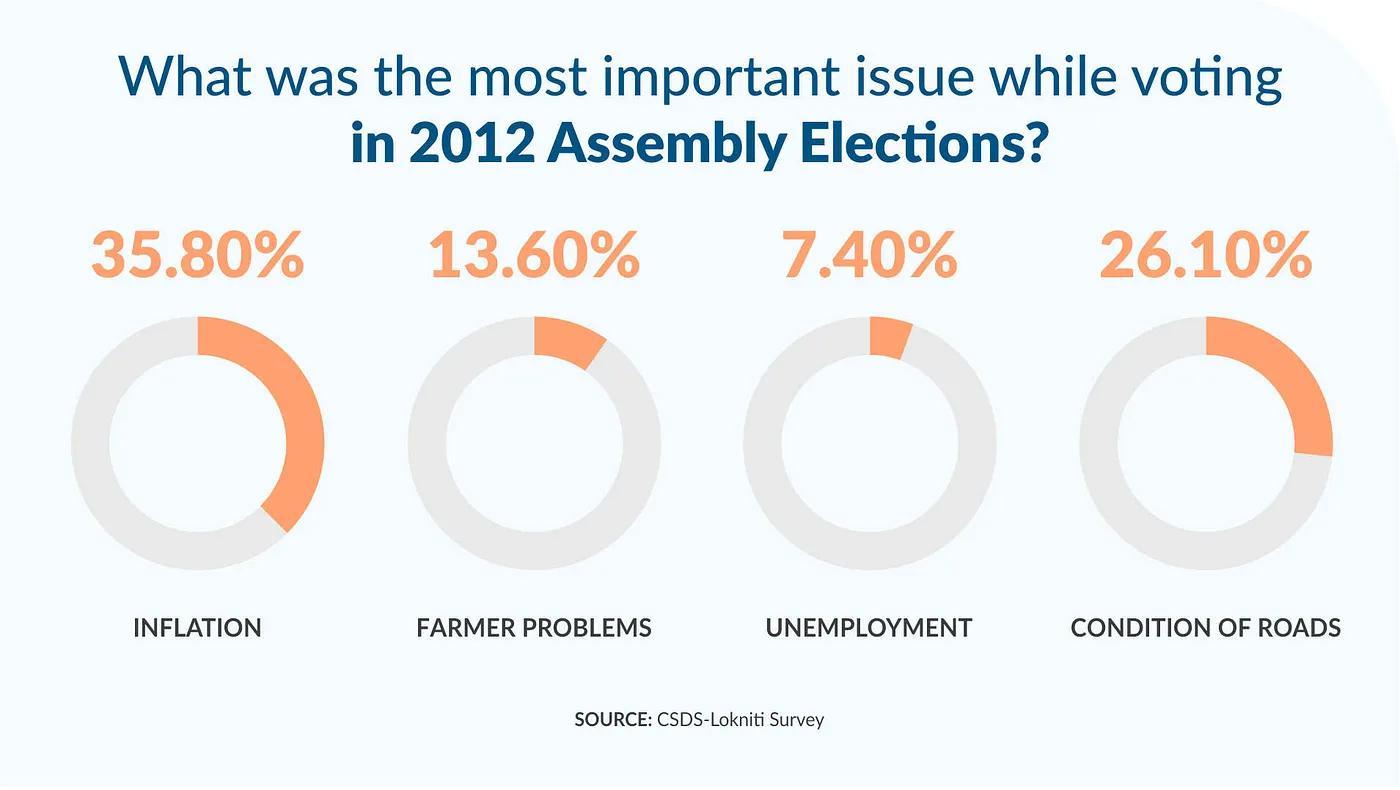

This is not the first time that farmers in Uttar Pradesh are expressing their anger against the BJP ahead of an election. In 2016, they had shown ire towards the party because of demonetisation and its harmful impact on the agricultural economy. Additionally, the farmers in UP were also upset with the government in the run-up to the 2017 assembly polls and before the 2019 Lok Sabha election, in the face of a declining economy and subsequent rise in farmers’ suicides, as well as the issue of non-payment of dues by sugar mills.

In the last few months, apart from the dissatisfaction against the three farm laws, farmers in UP have also complained about the rising prices of electricity, raw materials, and low minimum support prices compared to the cost of production. In an attempt to win farmers back, the BJP-led government has announced various Centre and state-sponsored welfare schemes and organized a huge farmer outreach programme, visiting 140 assembly segments in the state to hear the issues of the farmers.

Shreya Maskara /New Delhi

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Animesh Gadre, Damayanti Niyogi, Kavya Sharma, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.