Morbi Mishap: Rethink Public Infrastructure Management Urgently

The original version of the article was published on 4th November 2022 in “The Daily Guardian”

On 30th October 2022, the collapse of a suspension bridge in Morbi, Gujarat led to the death of over 140 citizens, with several reported missing and injured. The bridge over the Machchhu river was more than a century old and was thrown open just four days ago after nearly seven months of closure for repair and renovation. The collapse of the bridge and resultant deaths have pulled into action authorities from across the centre, state, and local administration. However, finer details create an image similar to most public infrastructure failures of the past in India. They involve a blame game between authorities and private contractors, setting up committees to enquire about the reason for failure and announcement of ex-gratia to next of kin of the dead and the injured.

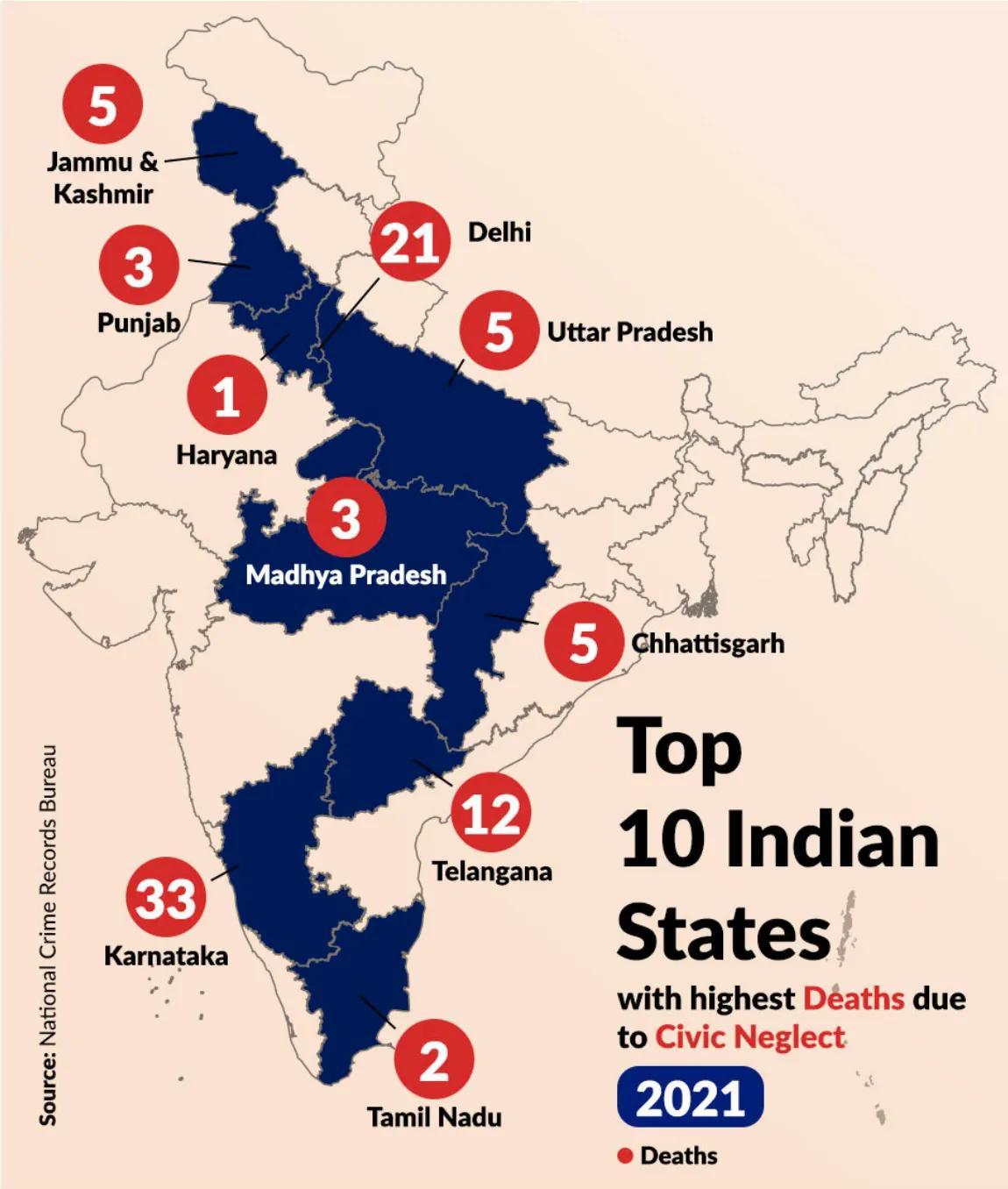

Unlike several public infrastructure failures in the past, the Morbi bridge collapse should not turn into just another breaking news incident. It must be a turning point in improving the condition of public infrastructure management which is essential to prevent future occurrences of similar incidents. The bridge collapse is not a loner in infrastructure failures leading to such a high death count. While there has been a decline in the incidents and the death toll due to public infrastructure failures over the last several decades, the reasons for most failures are preventable through proper oversight and procedural follow-ups.

A Repeat of Mistakes: Past Bridge Failures

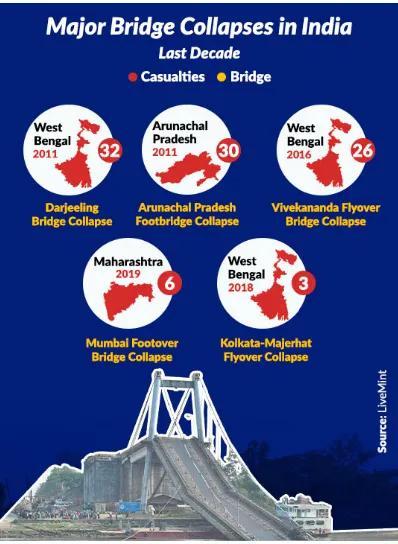

Other public infrastructure failures of the past leading to a high fatality rate include the Darjeeling Bridge collapse in West Bengal (October 2011) that left 32 killed and 60 injured. According to reports from the time, the bridge suffered heavy damage during the September 2011 earthquake and a lack of a proper check for damages after the natural disaster was the main cause behind the collapse. The collapse of a footbridge in Arunachal Pradesh in the same month killed 30 people, mostly children. Built in 1987, the bridge collapsed due to heavy load, with over 63 people on it at the time of the incident.

The March 2016 Vivekananda Flyover Collapse in West Bengal presents another case of public infrastructure failure in India. According to reports, the collapse of the under-construction flyover was due to negligence in quality check, faulty design and use of improper construction material. 26 people were killed and 60 injured in the incident even as IVRCL Infrastructure and Projects Pvt. Ltd., incharge of constructing the flyover, shrugged off responsibility by describing the collapse as an “act of God ‘’.

More recently, the Kolkata-Majerhat flyover collapse in September 2018 and the March 2019 Mumbai foot overbridge collapse in Maharashtra, while led to fewer casualties and injuries (three and six people killed and over 24 and 30 injured respectively), both draw a similar picture of negligence by authorities to conduct timely inspections and supervision. The Kolkata-Majerhat flyover was visibly damaged after weeks of continuous rains and proper inspection, closure and repairs of the bridge could have prevented the tragedy. In the 2019 Mumbai bridge collapse, similar to Morbi, the bridge was old and was audited fit for use just six months before the incident.

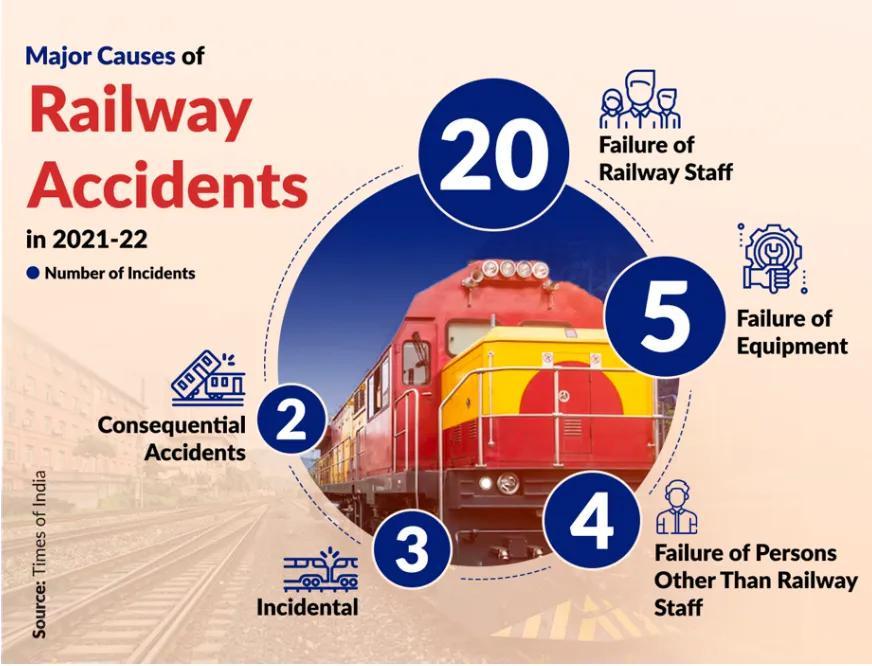

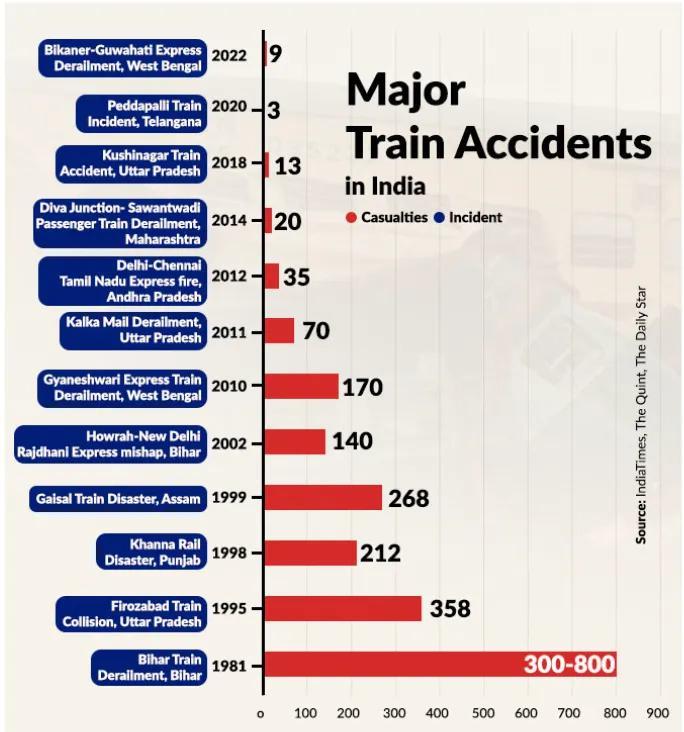

Other major public infrastructure failures include train derailments, accidents on roads and highways due to black spots, and hospital fires most involving human negligence on the part of the immediate service providers coupled with the local authorities’ inability to regularly inspect and enforce existing safety standards.

The 2021 Madhya Pradesh Hospital fire due to a short circuit at the paediatric critical care unit of Kamla Nehru hospital in Bhopal leaving four infants dead, a major fire at a hospital and cancer institute in East Delhi in 2017 requiring immediate evacuation of all 92 patients, and a fire at a COVID-19 ICU ward of the district hospital in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra (2021) resulting in the death of 14 are all cases in point.

In all three cases, hospitals lacked safety measures suggested by the local civic bodies, but the incidents also indicate negligence on part of local authorities in taking timely action through inspection and enforcement of safety rules and regulations.

The Blame Game

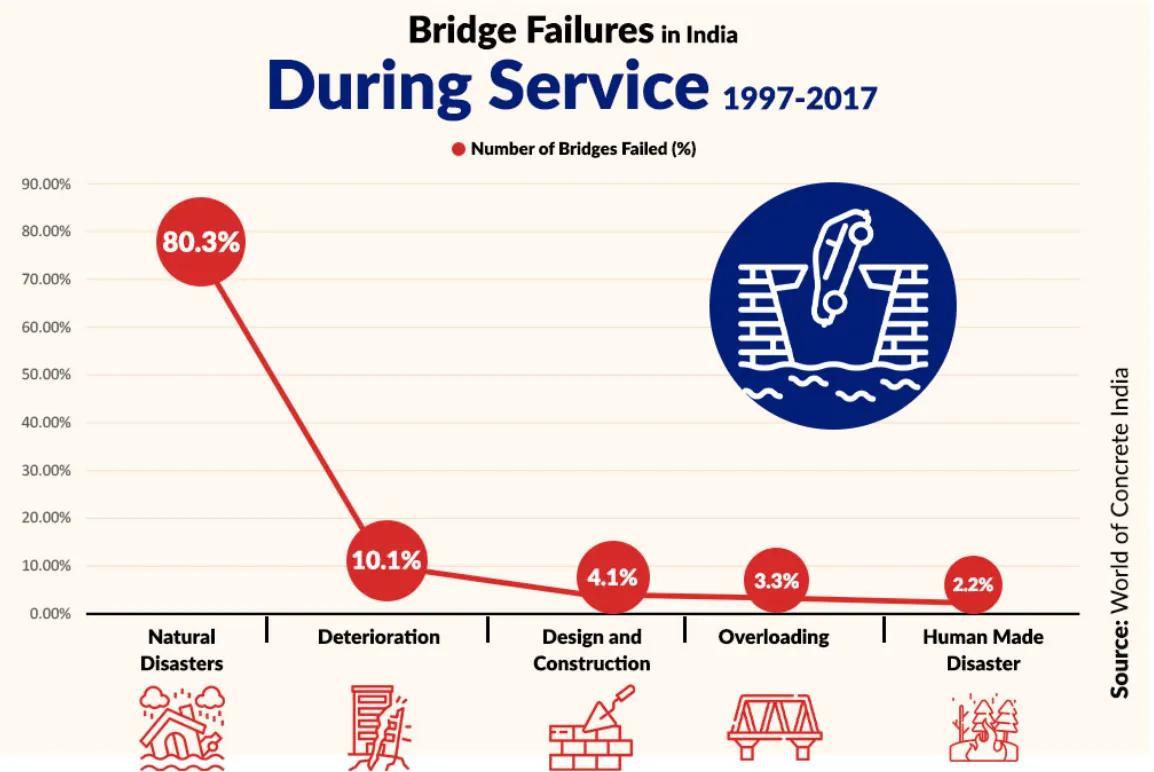

A 2020 study on ‘Analysis of bridge failures in India from 1977 to 2017’, published in the international journal ‘Structure and Infrastructure Engineering’, states that as many as 2,130 bridges — excluding culverts and pedestrian bridges — have failed to provide the intended service or collapsed during various phases of construction in the last four decades. The deterioration of material besides natural disasters was the reason for 10.1 per cent of bridge failures, while overloading contributed to 3.28 per cent of bridge failures. Morbi bridge, which was nearly 150 years old, had a sanctioned load capacity of about 100–150 people at a time, but had more than 500 visitors on the bridge at the time of the 30th October incident.

District Authorities have attempted to shrug off responsibility by passing the blame on the firm contracted for repair, maintenance and operations of the bridge, a trust owned by private company Oreva — manufacturer of small household items such as Ajanta clocks apart from battery-operated bikes. Local officials claim that the firm failed to obtain a fitness certificate from the municipality to recommence operations after the seven-month shutdown for repairs. According to the Morbi municipality, the owner of the bridge, and the one in charge of conducting safety inspections and enforcing safety rules for local public infrastructure, the firm failed to inform them of the reopening on the 26th of October thereby not giving them enough time to conduct inspections before the recent tragedy.

The aftermath of most infrastructural failures in India, whether or not leading to a high death count, somewhat lead to a similar fate. Police move in to arrest the immediate culprits, and government action involves suspending officials and persons responsible for operations followed by announcements to set up a committee to enquire about the incident. Financial support is also promised to the families of the dead and injured. However, little is done to improve the status of public infrastructure.

In Morbi too, just like other bridge collapses in the past, local police have arrested nine people, all associated with Oreva group, the firm contracted to maintain and operate the bridge. The accused include managers, ticket booking clerks (all employed by Oreva), two people contracted to repair the structure, and security personnel at the bridge. As of now, municipal authorities and officials, responsible for maintaining public infrastructure and preventing threats to the lives of citizens through proper oversight and inspection at regular intervals, have not faced any action.

Gujarat Chief Minister Bhupendrabhai Patel announced an ex-gratia of Rs 4 lakh to the family of each deceased and Rs 50,000 to the injured in the Morbi Tragedy. The PM office also announced an additional ex-gratia of Rs 2 lakh for the families of those who died in the incident apart from Rs 50,000 for the injured. State Home Minister Harsh Sanghavi declared that those found guilty will be strictly punished and a criminal case will be registered against them. In line with the usual responses in cases of public infrastructure failures, a five-member committee has been set up to enquire about lapses in the renovation of the 150-year-old suspension bridge. However, there is a clear need to go beyond the initial action of financial support, police arrests and setting up red-tape committees to enquire about and study the failures.

Need for Clear Guidelines, Institutional Oversight Mechanisms and Enforcement

Repeated occurrences of infrastructure failures due to preventable reasons call for a need to set in place procedures for selecting firms to do repairs, proper inspections and audits by municipalities and civic engineers before throwing open the structure to large-scale public use. Clear-cut rules and regulations in using high-quality construction material during initial construction and follow-up repairs and maintenance are also needed. However, setting up an institutional mechanism for supervision, inspection and approvals essentially needs to be coupled with strict enforcement of the rules without which no set of policy measures will yield the desired results of preventing death tolls and loss of public money.

The lack of above-mentioned measures appears to be behind the Morbi bridge failure too. Experts are citing several reasons for the bridge collapse ranging from improper repair and maintenance, inability to regulate the crowd and failure to conduct inspections and security checks before opening the bridge for public use. According to Sudib Kumar Mishra, associate professor at the Department of Civil Engineering at IIT-Kanpur who specialises in structural engineering, the sudden collapse of the bridge suggests that most or all the suspension cables were either weak or corroded, most likely due to wear and tear over years. According to several reports, the incident can be attributed to the old age of the bridge. However, repairs to the bridge were completed just a few days ago to fix the deterioration in cables and other parts of the structure. In the event that the damages are irreparable, civic authorities should have kept the bridge closed for public use.

Poll-bound Gujarat is already witnessing a politicisation of the heart-wrenching tragedy which has seen more than 140 die even as the death toll increases every day. Opposition parties, the Aam Aadmi Party and the Indian National Congress are leaving no stone unturned in slamming the incumbent BJP which has been ruling the state for more than two decades and also runs the Morbi Municipality. However, the tragedy calls for all stakeholders to come together and put in place strong mechanisms to prevent the repeat of another Morbi in Gujarat or anywhere else in India.

Damini Mehta/New Delhi

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.