PM Garib Kalyan Yojana: A Seventh Extension Unlikely?

The original version of the article was published on 16th September 2022 in “The Daily Guardian”

Meant to provide support to the most vulnerable sections of society during the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) has come to witness several extensions over the last two years. The scheme is currently in its sixth phase and provides free foodgrains to the poor, as well as migrants, with the intended purpose of ensuring food security and providing relief to low-income households affected by the pandemic.

It falls under the umbrella of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Package, which was also launched during the first lockdown. The scheme provides an additional five kilograms (kg) of free foodgrains (wheat or rice) to every person covered under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 over and above the pre-existing five kg of subsidised foodgrain available through the Public Distribution System (PDS).

Targeting upwards of 80 crore beneficiaries under NFSA across the country, the scheme was initially announced for three months from April 2020 to June 2020. It has been extended several times since then and its sixth phase will end on 30th September 2022.

However, with increasing demand for an extension from states across the country, premised on both the continued impact of the pandemic and its deadly waves on citizens, keeping in mind the scheme’s impact on the upcoming state polls, the ball lies in the centre’s court on extending the scheme for another term.

IMPROVING FOOD SECURITY

With an ongoing debate on the distribution of ‘freebies’ or public goods and services free of cost to certain sections of society, the benefits of distributing free grains under the PM-GKAY have also come under the scanner. On one hand, there are reports and surveys, either commissioned or cited by the government, which point towards the benefits of the scheme; several other independent surveys highlight its failings in reaching a larger section of society in need of government support.

A survey commissioned by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution and conducted by Dalberg claims the scheme has shown high levels of satisfaction among beneficiaries. Another survey conducted in July 2021 by Microsave Consulting (funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) and cited by the government, reported that an average of 94 per cent of households received free ration on a monthly basis. The survey was undertaken in 88 districts across the country.

However, not all surveys refer to the scheme and its impact positively. Independent surveys, conducted to assess the benefits of the scheme for low-income groups who are said to have borne a larger brunt of the pandemic, paint a grim picture. Findings from one such survey conducted by Azim Premji University, indicate that more than 68 per cent of households did not receive the free foodgrains assured under the scheme. Conducted by the Centre of Sustainable Employment at the University, the survey went on to report that only 27 per cent of the eligible households reported receiving the full benefits under the larger Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, the parent scheme of the PM-GKAY. Findings of a survey conducted by the Right to Food Campaign (RTFC) and the Centre for Equity Studies’ Hunger Watch further the argument against the PM-GKAY’s ability to provide food security to the needy. Released in December 2020, the survey noted that 45 per cent of respondents found their need to borrow money to purchase food had increased in September-October 2020 compared to pre-pandemic times. According to the same survey, about 27 per cent of respondents sometimes went to bed without eating. The survey was conducted in 11 states in India from September to October 2020, five months after the government lifted the first lockdown imposed in March and continuing up to May 2020.

PHASE WISE ALLOCATION AND DISTRIBUTION

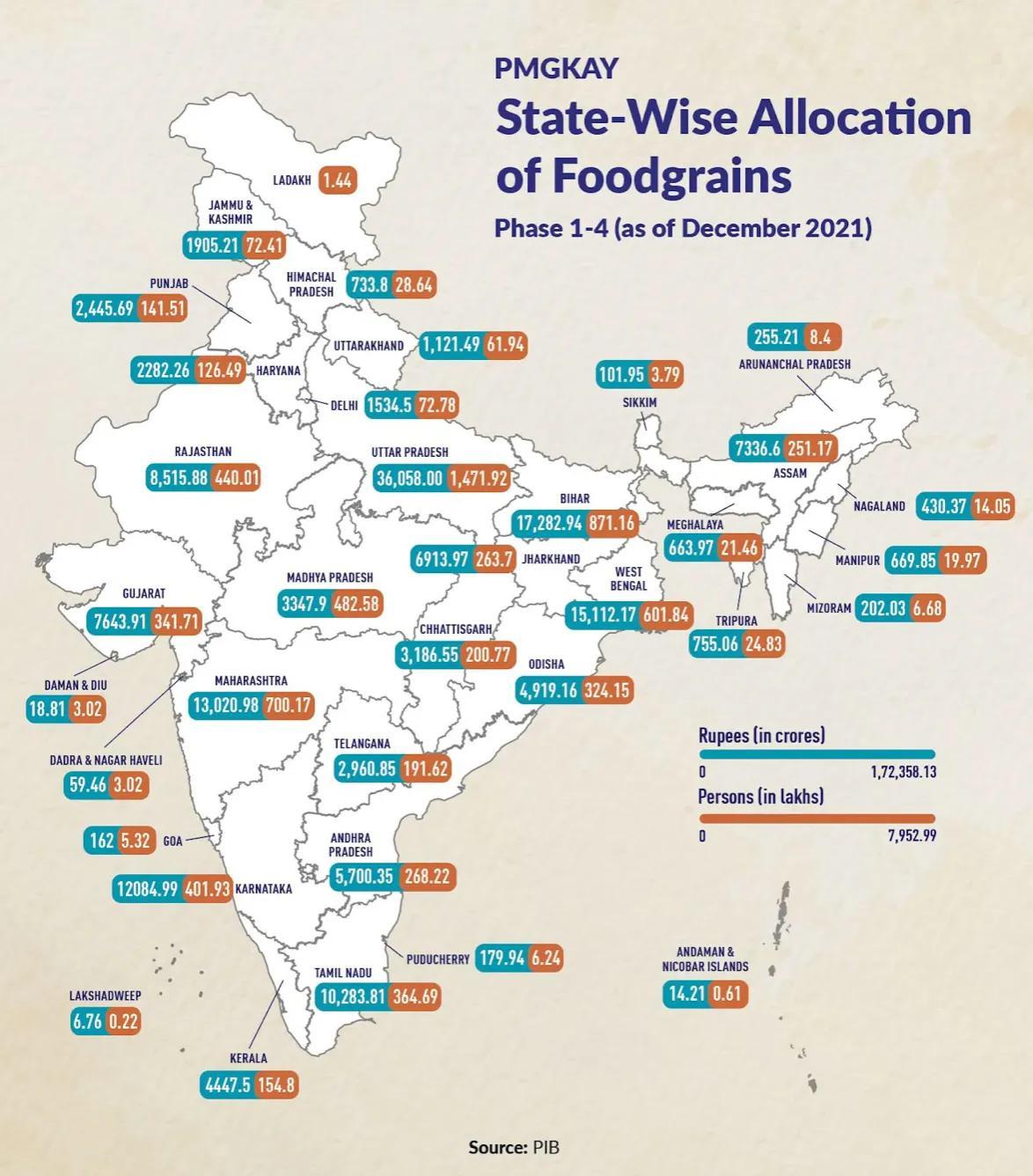

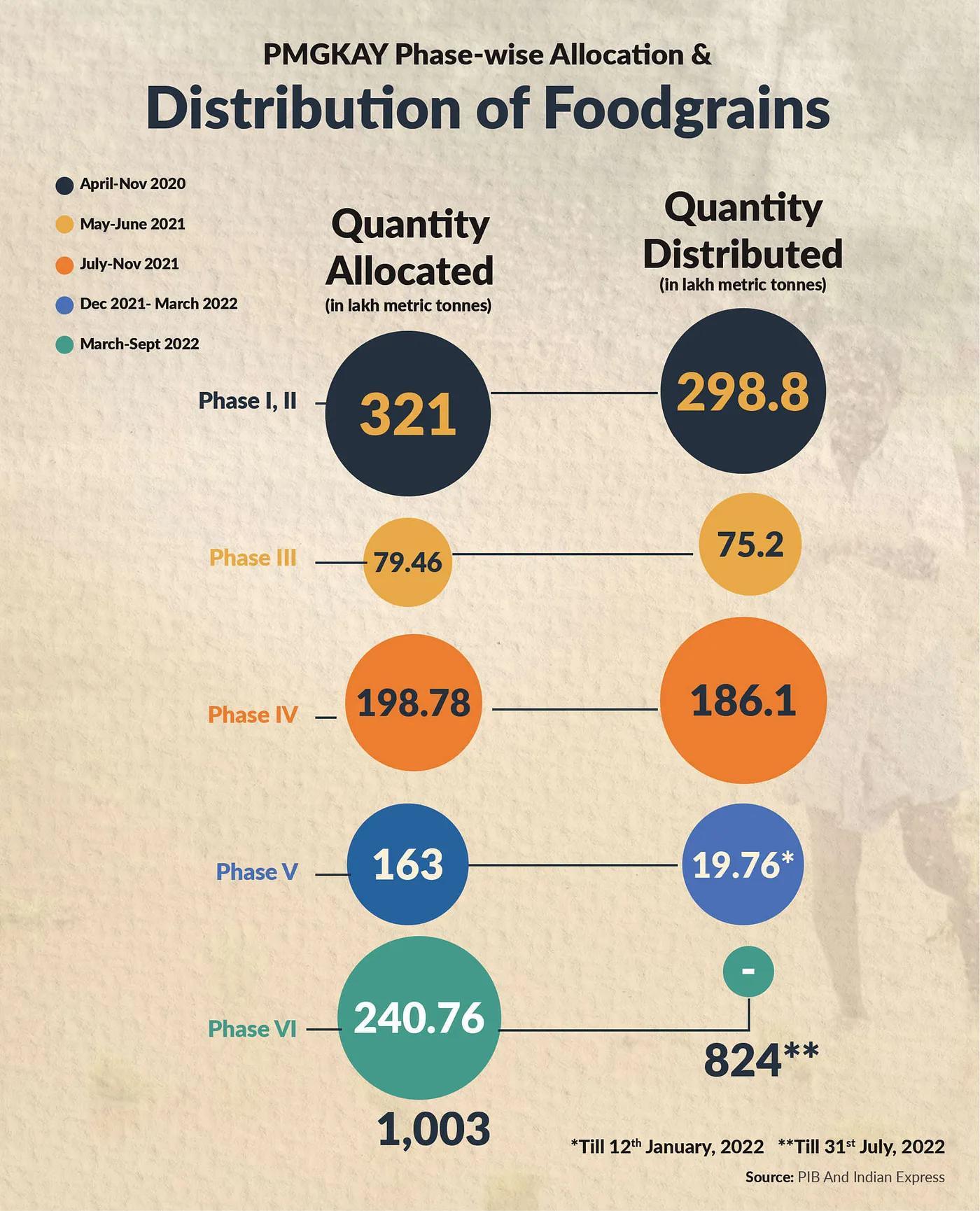

The scheme has witnessed large-scale allocation of foodgrains from the central government’s Food Corporation of India (FCI) pool to states. In phases I to V of the scheme, the Department of Food and Public Distribution (DFPD) allocated a total of 759 lakh Metric Tonnes (LMT) foodgrains to states and Union Territories (UTs) for distribution to around 80 crore NFSA beneficiaries.

However, of the 759 LMT foodgrains allocated to the states and UTs, a cumulative total of about 580 LMT of foodgrains was distributed to the beneficiaries in the first five phases. Cumulatively, a total of 1,003 LMT food grains have been allocated by the Centre in all six phases of which 824 LMT was distributed up till 31st July 2022. There is a clear gap between the foodgrains allocated by the Centre’s assessment of the public need and that which was effectively distributed and / or availed by the beneficiaries. The foodgrains are distributed free of cost and have entailed a fiscal bill upwards of Rs. 2.79 lakh crore in food subsidy till 31st July 2022 for the six phases.

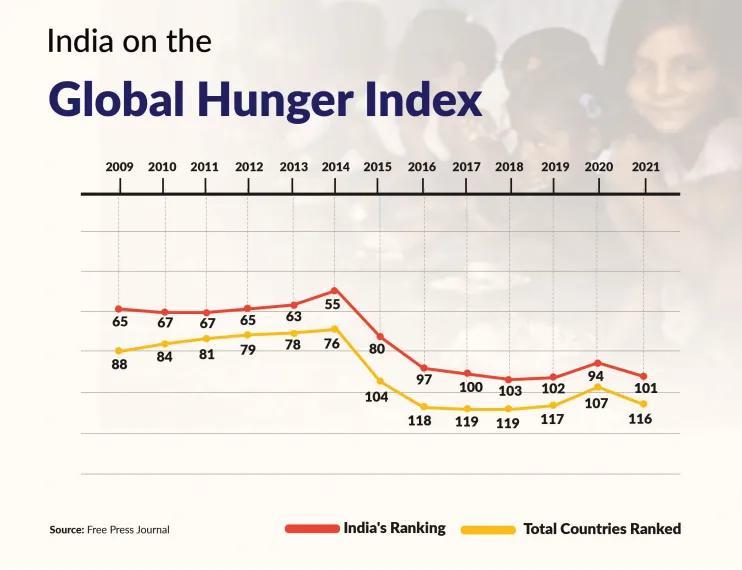

States have recorded varying successes in the distribution of food grains. While Mizoram, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, and Sikkim were rated the best performing states in the first two phases of the scheme, Chhattisgarh, Tripura, Mizoram, Delhi, and West Bengal topped the list by the end of the third and the fourth phases. While some in the government claim that the scheme’s extension five times was proof in itself of its success, the COVID-19-induced loss of livelihood and income, accompanied by a drop in the country’s ranking in the Global Hunger Index (from 94 in 2020 to 101 in 2021), point towards the scheme’s inability to provide food security and support to the lowest income groups.

The sixth phase of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana is slated to expire on 30th September 2022. Gujarat, with a BJP government, and Rajasthan, with a Congress government, are requesting an extension of the scheme beyond its September 2022 deadline. Gujarat Food & Civil Supply Minister Naresh Patel is likely to request the Central government to extend the scheme till Diwali (October 2022).

Rajasthan’s Minister for Food and Civil Supplies Pratap Singh Khachariyawas clearly demanded the Centre must continue the PMGK Anna Yojana beyond September and also urged the Centre to increase the limit for the number of NFSA beneficiaries for states.

According to Khachariyawas, an upper cap set by the Centre on the number of beneficiaries has severely constrained states’ abilities to help those in need of free grains. This is even as, in cumulative terms, the states have failed to distribute the entirety of the Centre’s allocation of foodgrains.

Uttar Pradesh, with BJP’s Yogi Adiyanath at the helm and Bihar, which recently witnessed a breakup of the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, has left it to the Centre to take a final decision on the extension of the Union government scheme.

Punjab and Maharashtra too are willing to follow the Centre’s lead on it. Several other states like Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana are likely to extend the scheme as they already have their own free foodgrains scheme and have claimed they would continue to distribute foodgrains free even if the Centre ends the scheme come September.

WHY AN EXTENSION IS UNLIKELY

Retail inflation in India, measured by the consumer price index (CPI), spiked to 7 per cent in August 2022, up from 6.71 per cent in July even as wholesale inflation in India (measured by the Wholesale Price Index) eased from 13.93 per cent in July 2022 to 12.41 per cent in August.

According to analysts, a rise in the consumer price index, that directly affects the local consumer, would add to the woes of the vulnerable sections. In this scenario, when inflationary pressures are likely to burden household budgets, a scheme such as the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana may help mitigate the impact of rising prices, especially food bills that take up a large share of the income of households below the poverty line.

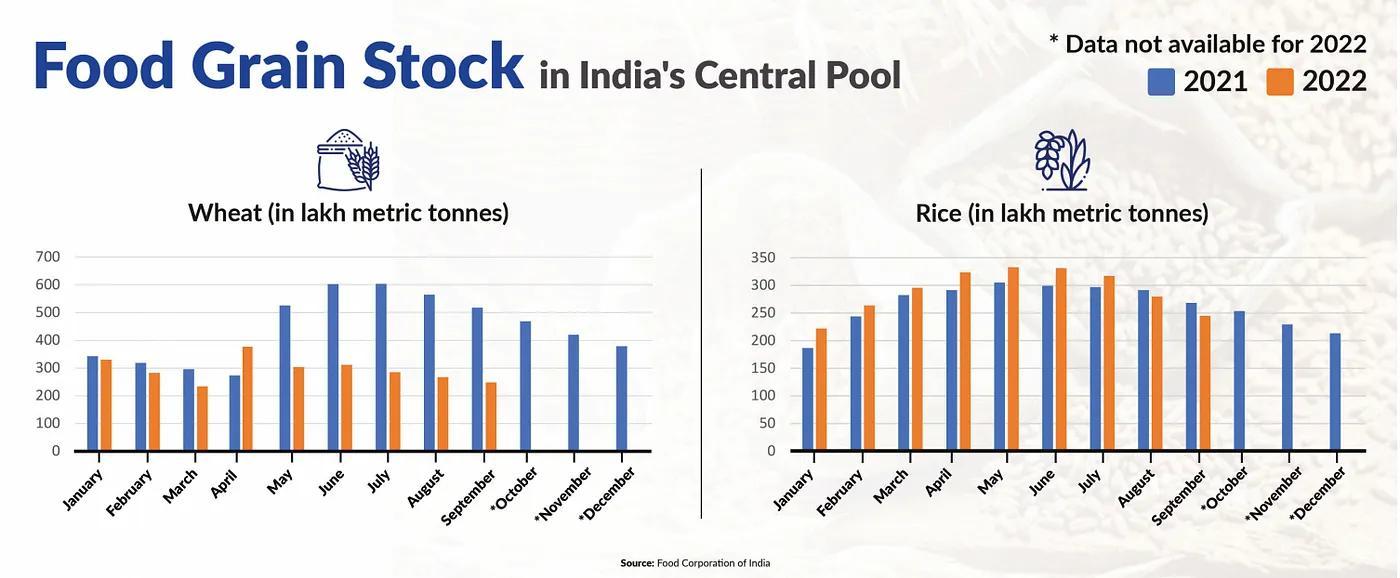

However, it is noteworthy that the Centre’s decision to extend the PM-GKAY is not dependent solely on rising prices or the subsidy bill. While deciding on the extension of the scheme, the central government is factoring in the availability of foodgrains stocks in the central pool in light of the weak monsoon and consequent loss of crops.

According to the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, the scheme was extended to September 2022 and is most likely to go up till March 2023, as demanded by several states, which may have an adverse impact on the rice stock in the central pool.

POOR MONSOON AND BURDEN ON GOVERNMENT FOOD GRAIN STOCKS

The burden on the government stocks in the form of increased demand to allocate grains may drop the buffer stock of rice by 22 lakh tonnes thereby costing the exchequer around Rs. 90,000 crore in subsidy.

The scheme has already cost nearly Rs. 2.6 lakh crore since its inception in 2020. Rice stocks of the FCI, in charge of procuring and maintaining foodgrains for the central government, are estimated to be 11.4 million tonnes (mt) in April 2023, against the buffer norm of 13.6 mt, if the free foodgrain scheme is extended. The wheat stock may fall to 9 mt against the buffer of 7.4 mt on 1st April. Recent drought-like conditions in several states due to a poor monsoon have impacted rice production thereby increasing pressure on the country’s wheat stocks.

Indicating the Centre’s unwillingness to extend the scheme, in a statement as early as June 2022, the Expenditure Department of the Union government said, “The free food grain for poor scheme PM-GKAY should not be extended beyond September as it could strain government finances.” Further reinforcing the benefits the scheme has brought, the Department also said the high food security cover has already “created a serious fiscal situation” and is not needed in non-pandemic times.

Damini Mehta/New Delhi

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.