Rising Unemployment In India During Pandemic

The Original Version of this article was published on 12th January 2022 in “The Daily Guardian.”

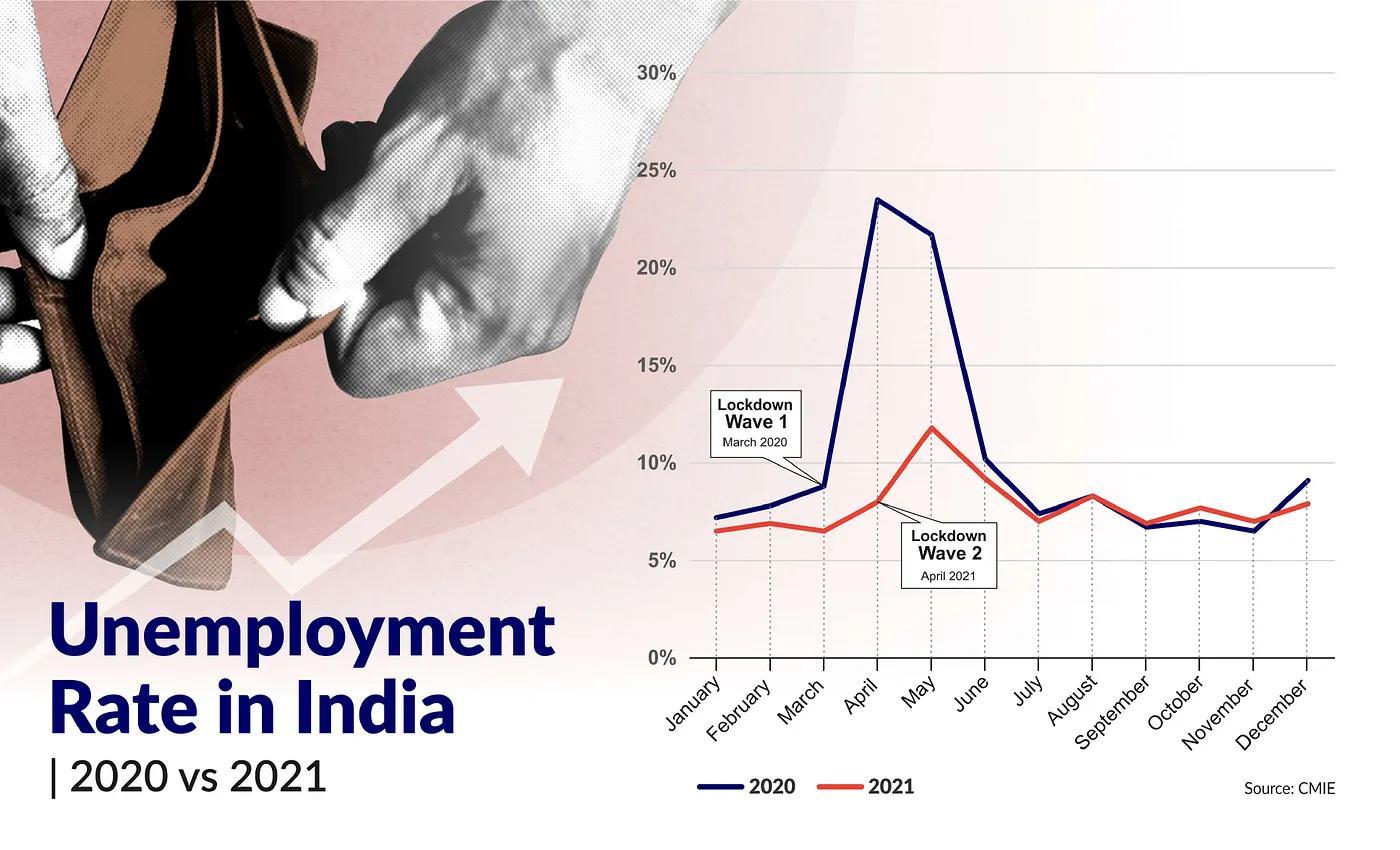

The rate of unemployment in India hit 7.9 per cent in December 2021. In fact, in the last three months of 2021, the rate of unemployment has been around 7 per cent or more. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the unemployment rate in the country has consistently been at odds with the various restrictions and lockdown measures imposed by state and central governments, as well as the overall economic outlook of the country. While the figures from 2021 are slightly better than those recorded in 2020, they are still very high compared to levels experienced in the recent past. The unemployment rate was 4.7 per cent in 2017–18 and 6.3 per cent in 2018–19.

India’s growth recovery, which started to gather momentum by the end of 2021, has yet again taken a back seat in the light of the third wave. As state governments across the country start imposing measures such as night and weekend curfews and the closure of certain industries, the Indian economy, which has already been struggling for the last year and a half, seems unlikely to get a breather anytime soon.

Which Industries Suffered the Most

The industry-wise breakup of employment — of the difference between employment in December 2021 and 2019–20 — conducted by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), shows that the manufacturing sector has lost 98 lakh jobs, while construction and agricultural jobs increased by 38 lakh and 74 lakh, respectively. Additionally, the service sector witnessed a net loss of 18 lakh jobs, hotels and tourism lost 50 lakh and education lost 40 lakh jobs and retail trade gained 78 lakh jobs. Since the onset of the pandemic in 2020, India’s micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which contribute 30 per cent of the nation’s GDP and half of the country’s exports and represent 95 per cent of its industrial units, have been struggling to survive. In December 2020, 9 per cent of MSMEs shut down or were scaled down. Similarly, in May 2021, 6,000 MSMEs and 59 per cent of startups shut down or scaled down, unable to cope with rising inflation and prices. This further increased the already rising rates of urban and rural employment.

In December 2021, with the emergence of the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus, consumer spending took another hit, as economic activity reduced in light of government restrictions and an overall decrease in consumer confidence in the economy. With the renewed restrictions imposed by the government, unemployment in certain industries, including hospitality, tourism, MSMEs, IT, trade, and manufacturing is likely to be negatively affected. As governments impose restrictions on the movement of people during the third wave, the hospitality industry is set to face another tough year. According to rating agency ICRA Limited, the demand in the hotel industry will be curtailed in the fourth quarter of this fiscal year, at least in January 2022, due to the latest wave dampening sentiments. Hotels and resorts are likely to be amongst the worst hit within the hospitality industry during the third wave. This will also affect those directly and indirectly employed by the hospitality industry. Similarly, for businesses in the MSMEs sector, who have already exhausted their cash reserves while struggling to survive the impact of the first and second waves of the pandemic, the only way to survive the third wave is likely to be one with extreme cost-cutting, particularly of personnel. The effects of this will be especially visible in the blue-collar jobs and if it is likely to persist longer, it could seep into white-collared jobs and overall larger enterprises.

The trade industry is also likely to experience the impact of the highly contagious Omicron variant. As per the Federation of Indian Export Organisations (FIEO), the restrictions this time around are likely to impact global demand and disrupt supply chains, which have not yet returned to normalcy. Indian exporters of leather goods, garments, and carpets have begun to witness a fall in orders from Europe, requests to push deliveries by a few weeks, and queries related to various restrictions being put in place to control the spread of the Omicron variant. Traders have also noted that the likely manpower crunch — especially in logistics — high freight costs, and restrictions across the globe could dent India’s exports in the first quarter of 2022.

As per some experts, the economy is going to witness an unusual K-shaped recovery curve, whereby certain industries and individuals pull out of a recession, while others stagnate. This would mean that while some sectors/sections of the economy are likely to register a very fast recovery, many will continue to struggle. The impact of such a curve on the health of an economy is profound as this means that recovery is split along class, racial, geographic, or industry lines. This is likely to contribute to an overall rise in inequality. Many big firms in the formal economy have increased their market share during the pandemic, and this has come at the cost of smaller, weaker firms that were mostly in the informal sector and which could not withstand repeated lockdowns. This paints a worrisome picture for the Indian economy where almost 90 per cent of all employment happens in the informal sector.

Lessons from the First and Second Waves

Employment in India has not returned to the levels recorded prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and given the rising cases in light of the third wave, it is unlikely to anytime soon. During the first wave of the pandemic, the unemployment rate in India rose to 23.8 per cent in the week ending 29 March, 2020 — the first week when the lockdown was introduced — from 8.4 per cent in the preceding week. This data was collected from the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) of the CMIE and was the highest unemployment rate recorded since the start of the survey in 2016. Urban joblessness had hit a high of 20.8 per cent in April-June 2020 when the country was under a stringent lockdown following the pandemic. However, the country’s unemployment rate fell dramatically in June 2020 as restrictions were eased and people returned to work. After touching a high of 23.5 per cent in April and May 2020, the unemployment rate first dropped to 17.5 per cent in the first week of June 2020 and then took a steep fall to 11.6 per cent in the second week. Over 12.2 crore people in India lost their jobs in April 2020, according to estimates from the CMIE.

Around 75 per cent were small traders and wage labourers. As restrictions continued to be reduced, unemployment in the country reduced further and was recorded at 9.10 per cent in December 2020.

Following this, India’s second pandemic wave crashed the labour market in April 2021, erasing at least 73.5 lakh jobs. As per the CMIE, Over 1 crore Indians lost their jobs because of the second wave of the pandemic and around 97 per cent households’ incomes declined from the beginning of the pandemic. CMIE data also revealed that the number of employees, both salaried and non-salaried, fell from 39.81 crores in March 2021 to 39.08 crores in April 2021, in the third straight month of falling jobs. In comparison, in January 2021, the number of people employed in India was 40.07 crore. The employment rate fell from 37.56 per cent in March 2021 to 36.79 per cent in April 2021, hitting a four-month low. The number of people who were unemployed and not yet actively looking for jobs increased from 1.60 crores in March 2021 to 1.94 crores in April 2021. Under the pressure of reduced economic activity and multiple lockdowns, India’s urban unemployment rate soared to almost 18 per cent in May 2021, the highest in a year. After the peak of the second wave, similar to the first wave, things began to recover in July 2021. Since the beginning of July 2021, unemployment in urban India stayed below 9 per cent, and at the national level, it has remained under 8 per cent. This could perhaps be attributed to the fact that several industries and businesses in the second wave had learnt to deal with COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdowns in a better manner and perhaps had accounted for the same or adjusted their businesses to deal with their impact. The unemployment rate in India in December 2021 was recorded at 7.9 per cent and the estimated unemployment rate on January 2, 2022, is 7.8 per cent, according to a 30-day moving average.

As per economic experts, various policy decisions can help mitigate the impact of this unemployment crisis in the country. This can be done in two main ways: direct employment in government and employment into large private enterprises. In 2020, both the Government and private enterprises reduced their investments in infrastructure projects which led to fewer jobs being created. While the Indian government faced a setback because of the revenue demand, private enterprises were unwilling to work because of the contraction in sales and lack of demand. Since 2020, MSMEs have been shedding jobs, not possessing enough capital to sustain them, sending more and more people into unemployment. Experts suggest that the government should focus on fixing demand-side factors, which have continued to be adversely affected by the pandemic. This, along with accelerated infrastructure investment, will provide support to the economy and help recovery post the third wave of the pandemic.

Shreya Maskara/New Delhi

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Ananya Sood, Anurag Anand, Devak Singh, Narayani Bhatnagar, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.