The Cost of ‘Free’ Water

Note: The original version of the article was published on December 23rd in “The Daily Guardian”

In the last few weeks, the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation elections have been covered extensively in the news. In the run-up to the elections, various parties revealed their manifestos in order to attract voters. Free water supply was a common promise in the manifestos of all the parties. The ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) promised free water for all up to 20,000 litres, while the Indian National Congress promised up to 30,000 litres of free water for all.

Free water as an election promise is nothing new. The Arvind Kejriwal — led Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) promised the same to voters in the national capital in 2013. Several parties, including the INC in Rajasthan, have promised voters the same. Undoubtedly, the right and access to clean water is a human right and any political party in power should ensure the provision of the same for all. So shouldn’t the promise of free water supply by a political party be a great thing? However, this is not the case. We must remember that providing access to clean and safe water (especially a problem in rural areas) is a very different promise than providing free water supply as an election promise to all in an attempt to capture votes. The promise of free water supply often has conditions attached to it, such as the fact that recipients must have a metered water connection or connection to a piped water supply network. Due to the same, poorer sections of society and those living in rural areas who currently suffer the most from non-availability of water cannot avail the benefits of such a scheme. Let’s have a look at how the free water schemes implemented in Rajasthan and New Delhi have fared so far.

INC’s Free Water Promise in Rajasthan

Prior to the 2019 Rajasthan Lok Sabha elections, Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot from the INC announced a free water scheme for the state. Under the scheme, consumers living in urban areas would not be charged for using water (up to 15,000 litres) and in rural areas, the supply of water up to 40 litres per capita per day would be free of cost. Certain fixed charges would be levied on customers for meter service and innovation charges.

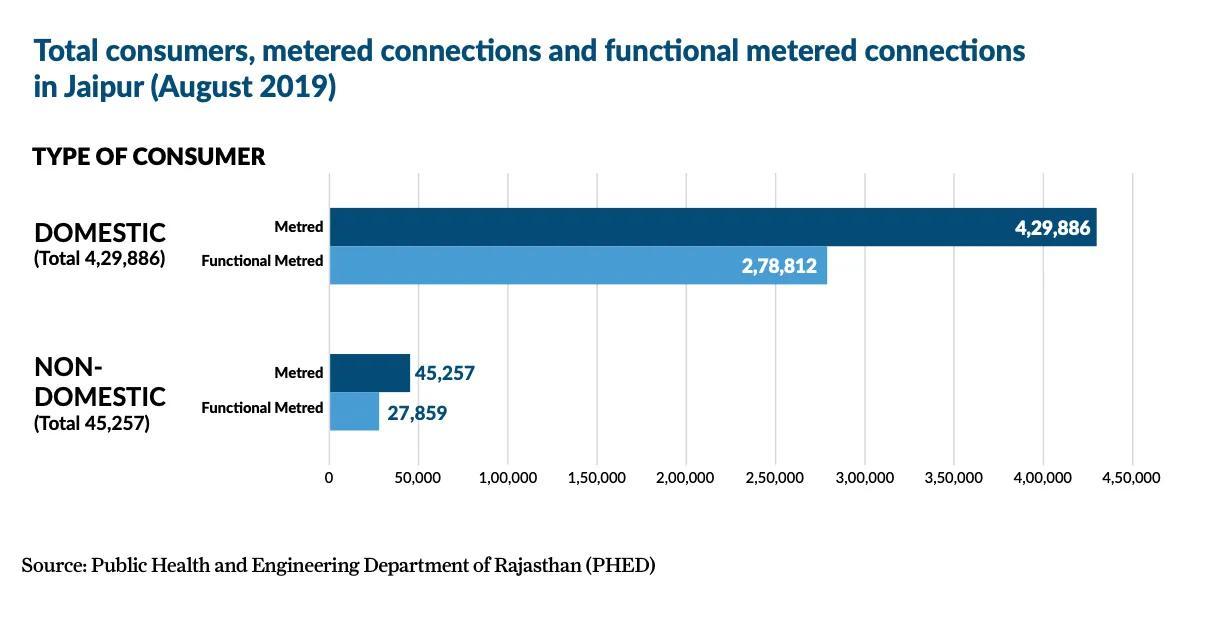

Now the question that arises is how successful was the scheme? The implementation of the free water scheme in Rajasthan was done quite differently from that in New Delhi, leading to a unique set of challenges. In June 2019, following the election, the Public Health and Engineering Department of Rajasthan (PHED) announced the scheme would only be applicable for those who already have a metered connection. This would mean that a significant portion of customers who do not have a meter, and who would arguably benefit most from the scheme would be left out. As of August 2019, in the city of Jaipur alone, around two lakh consumers did not have a metered connection. As per PHED officials, no information had been provided to install new meter connections. In fact, in 2018, under the Vasundhara Raje-led BJP government, 70,000 water meters were to be installed in Jaipur as part of the smart city project. However, this was much less than the requirement, and out of the 70,000 meters, only half were installed.

However, the problems of the scheme do not end here. The free water scheme put tremendous pressure on the PHED department, which had already been in losses over the years. For instance, in the year 2018–19, the revenue generated by the PHED was a mere Rs. 390 crore, in contrast to the expenditure of around Rs. 2,410 crores. The department spends on salaries, maintenance and repair, contract charges, delivery system, chemicals, while its only source of revenue is water bills collected from customers. A free water scheme such as the one announced reduces their income further. This begs the question: who really ends up paying for the “free” water being received by people?

AAP’s Free Water Promise in New Delhi

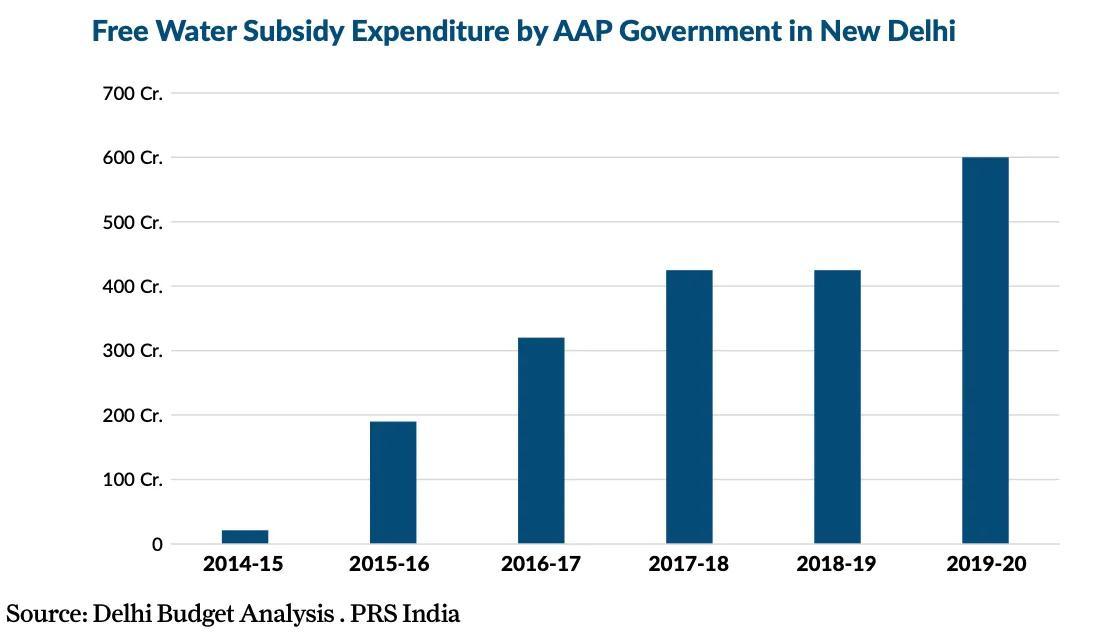

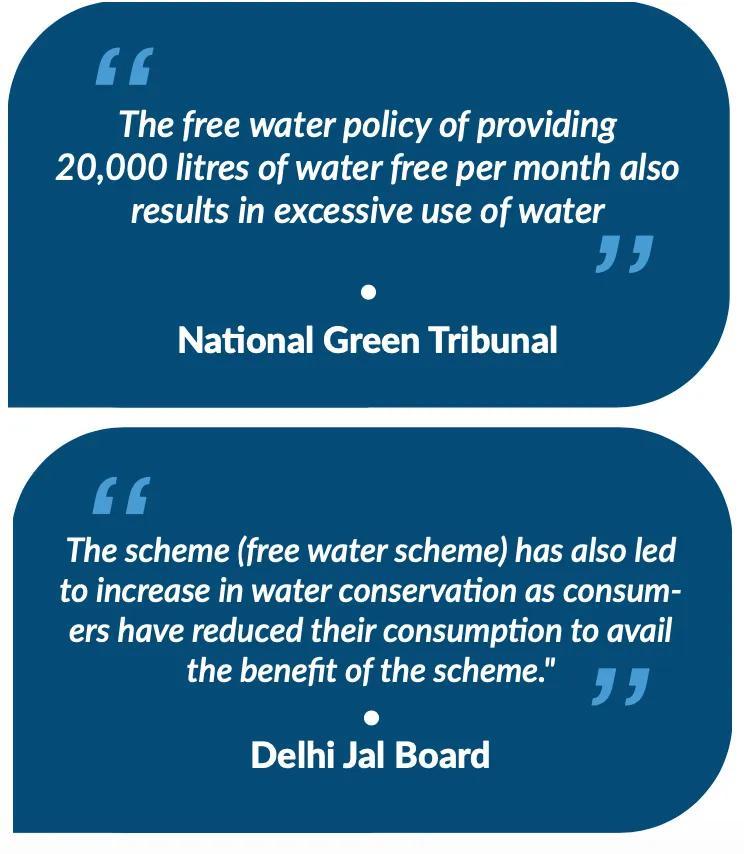

In 2013, as part of the AAP’s first manifesto, the party promised 20,000 litres of free piped water per household per day. The scheme was finally implemented in 2014, and once again during the run-up to the 2019 Assembly Elections in New Delhi, the incumbent Arvind Kejriwal made the same promise to Delhiites. This was coupled with the promise of 24*7 water supply as well. Responding to public interest litigation (PIL) in February 2019, the AAP government told the Delhi Assembly that the Rs. 400 crore water subsidy (for the year 2017–18) was benefitting 5.3 lakh residents of Delhi. In fact, the party also mentioned that the scheme had led to an increase in water conservation as customers wanted to avail the benefit of the scheme by reducing their consumption. They also reported that the implementation of the scheme led to an increase in the number of functional water meters across the city.

Based on these findings, it would appear that the scheme had been a success. However, was that really the case? Just months after that, in September 2019, the National Green Tribunal (NGT), which is a specialised forum for effective and quick disposal of cases related to environmental protection put out a statement saying the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) needed to take steps to prevent wastage of water in the city. What did the tribunal say? As per the monitoring committee (consisting of a retired high court judge and representatives from the DJB, Central Pollution Board and Central Ground Water Authority) reporting to the tribunal, various housing colonies were misusing the Delhi government’s scheme of providing 20,000 litres of water free of cost every month. These findings were in stark contrast to what the AAP government said earlier in 2019.

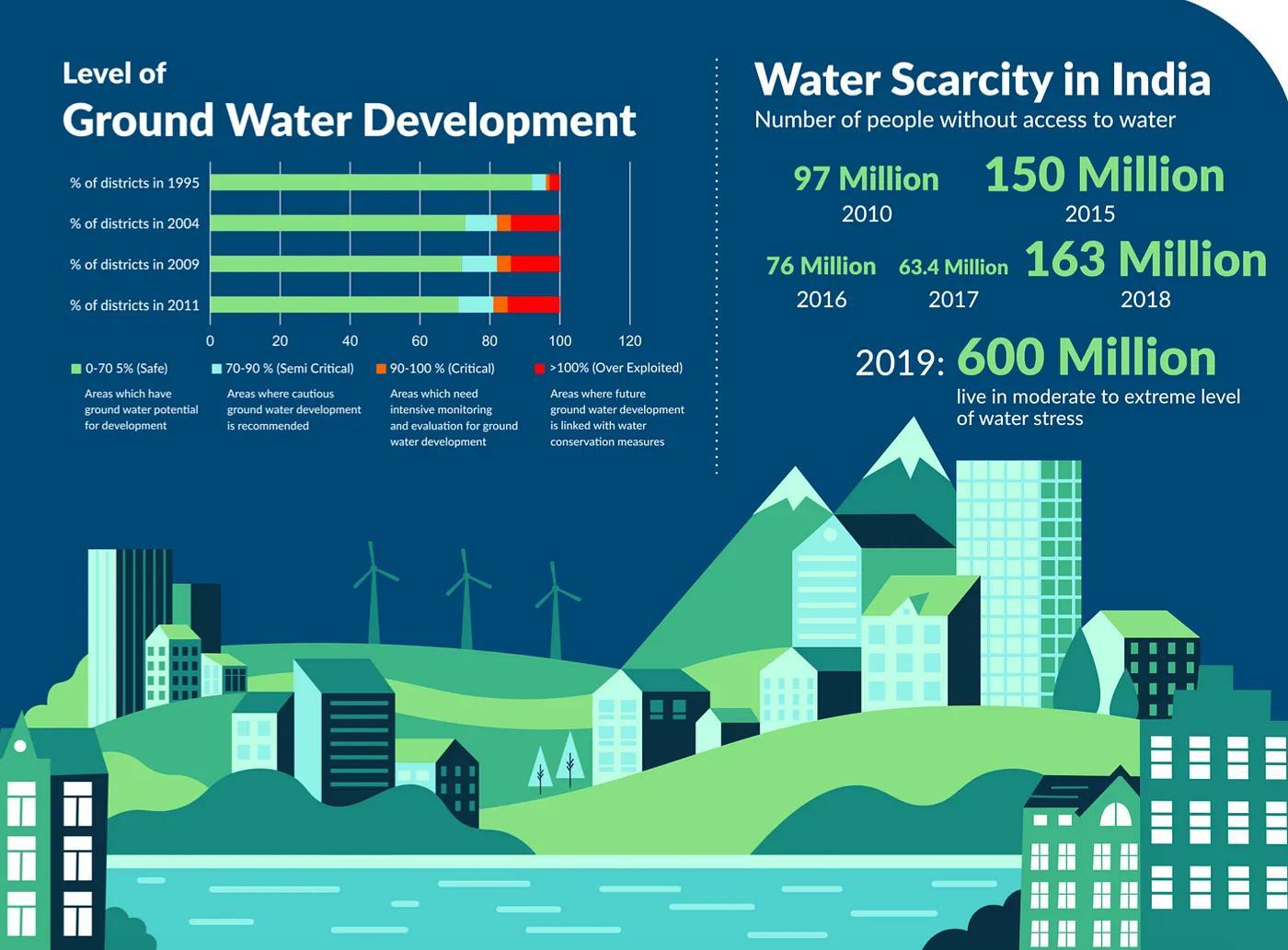

The monitoring committee also found that after extracting 20,000 litres of free water, several colonies were using borewells and tubewells to extract more water and avoid paying tariffs. At the time of the report, there were 17,062 illegal borewells in the city. This has increased to 19,000 as of July 2020. Not only this, but the committee also noted that the overuse of groundwater for drinking, irrigation and domestic purposes has led to its rapid depletion across the city. In fact, the water table has dropped more than 300 feet in many parts of the capital.

What did the NGT recommend?

Due to the alarming findings of the report, the tribunal recommended that a ‘polluter pays’ principle should be applied to fine those who wastewater. The report filed by the committee went on to describe, “In case water consumption is highly excessive, the consumer should be charged with higher tariffs for overuse.” Instead of having a free for all system, the panel recommended that there should be a system whereby those who use more, pay more. The system of more consumption, higher the tariff, along with an efficient monitoring system for water consumption, would minimise water wastage.

Understanding the cost of free water

In the past few years, various political parties across the country have been using ‘freebies’ ‘ such as free water supply to lure voters, many of whom probably don’t even have access to piped water supply and/or a metered water connection to avail the benefit of such a scheme. While political parties continue dangling the carrot of free water supply, not only is it leading to the wastage of water, but also taking away from the key issues of drinking water supply and water-borne diseases prevalent in the country.

Against global average of availability of freshwater of 7,600 cubic metres, India only has around 1,545 cubic metres available. 85% of rural households and 50% of urban households are dependent on the usage of groundwater and due to water wastage, the water table of many cities is depleting faster than one can imagine.

- Shreya Maskara /New Delhi

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.