The Left’s Declining Fortunes in India

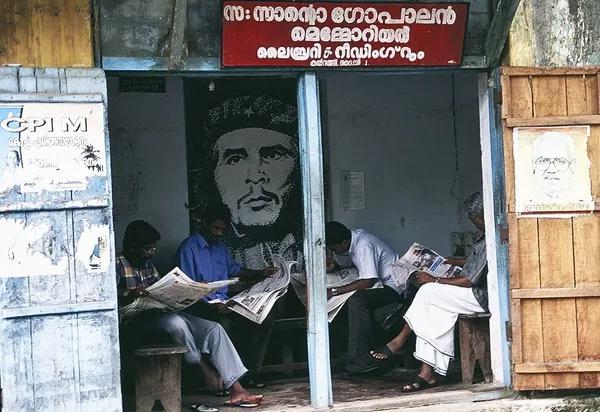

The Left’s inability to reinvent itself and its stubbornness to stick to the theories and slogans that defined their movement decades ago has made it obsolete in 21st century politics.

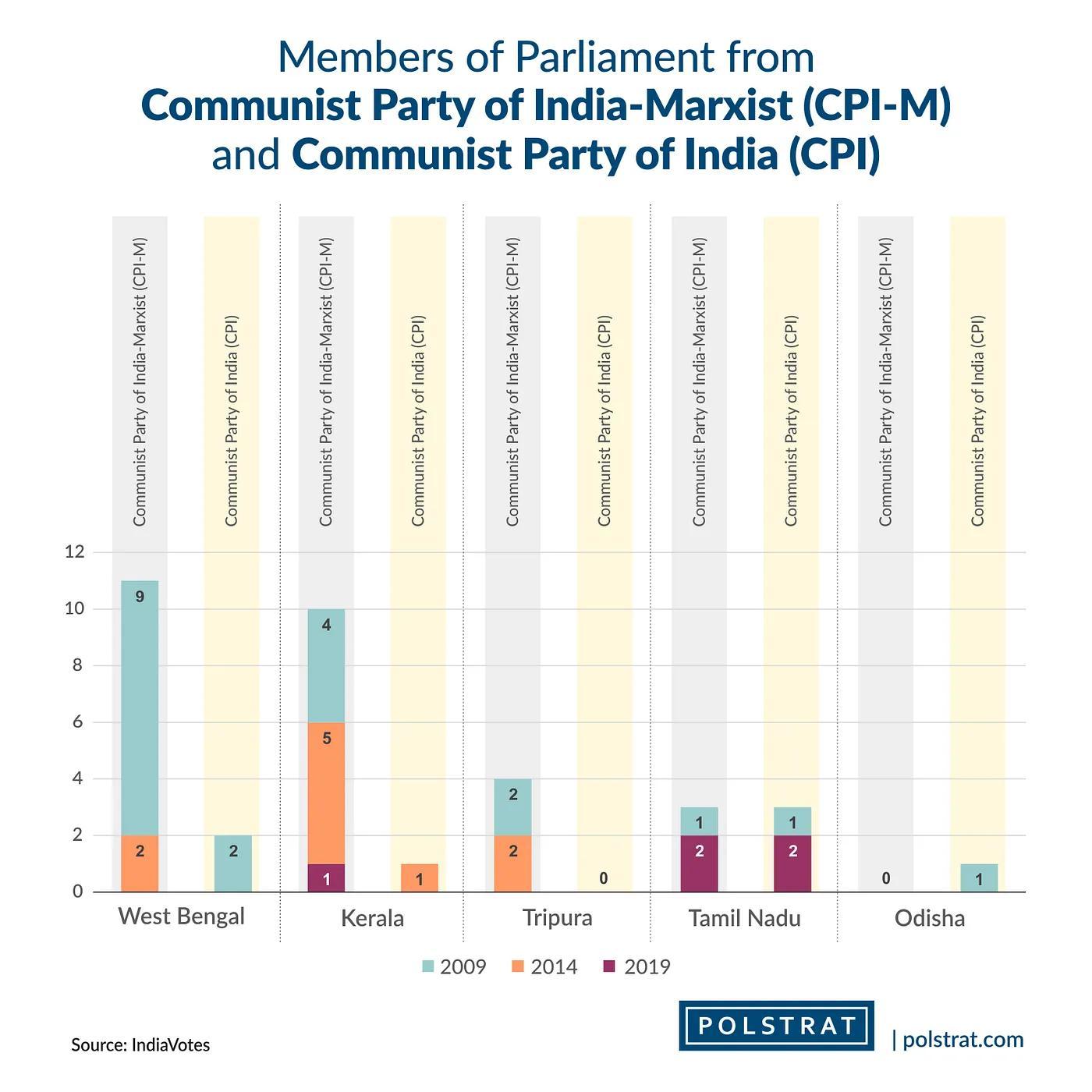

From ruling West Bengal for more than three decades and providing support to coalition alliances at the center, the Left has been reduced to a secondary space in the Indian political scenario today. The 2019 Lok Sabha Election and the 2021 Assembly Elections diminished the Left alliance and its two dominant parties- the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI (M)) and the Communist Party of India (CPI)- to a fraction of its former presence. The CPI (M) ruled Bengal from 1977 to 2011 but failed to win a single seat in the state in 2021. On the other hand, the CPI’s poor performance during the 2019 Lok Sabha Election with a mere 0.58% vote share and 2 seats has put it at the risk of losing its national party status if it fails to improve its performance by 2024 Elections. As of 2021, on its own, the alliance is in power only in the state of Kerala and is a part of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)-led coalition government in Tamil Nadu.

CPI emerged as the leading opposition in the 1952 Lok Sabha Elections, the first in the country. It went on to form the first Left government in the country after the 1957 Kerala Assembly Election. After that, the Left parties were mainly dominant in Kerala, West Bengal, and Tripura. The Left’s erstwhile dominance and its eventual decline call for a need to look at the Left politics in India from a fresh perspective.

Emergence of the Left on India’s Political Map

The Communist Party of India was formed on December 26, 1925, at the first Party Conference in Kanpur, then known as Cawnpore. It is the oldest communist political party and one of the eight national parties in the country. In the early years of independence, the undivided party led armed struggles against feudal lords and monarchs in states like Tripura, Telangana, and Kerala. However, after the Telangana Rebellion of 1946–51 led by the CPI against the Nizam of Hyderabad was brutally crushed, the party abandoned the policy of armed struggle. Over the next few decades, it adopted peaceful methods of organizing agrarian struggles, land reform, and trade union movements in Manipur and Bihar. The party’s successes in Bihar placed it at the forefront of the left movement in India.

Electorally, CPI gained prominence in 1952 when it emerged as the principal opposition party after the first general election to the Lok Sabha. The undivided Communist Party of India (CPI) won 16 seats in 1951–52 and 29 seats in the 1962 Lok Sabha Elections. In 1957, the CPI scored its first electoral success at the state level when it came to power in Kerala. However, ideological differences led the party to split as the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI (M)) came into existence in 1964. After the split, the CPI and the CPI (M) together bagged 42 seats in the 1967 Lok Sabha Election with a vote share of around 9 per cent.

The CPI (M) faced another split in 1967 when a faction composed of radicals broke away from the party on ideological grounds. According to the breakaway faction, the CPI (M)’s entry into parliamentary politics marked its abandonment of the original cause of the armed revolution. In 1969, even as the violent attacks at Naxalbari in North Bengal led by this group of radicals failed, the struggle established the roots of the Maoist movement in the country. Since then, the CPI (M) has emerged as the foremost Left force in the politics of India as its parent CPI was left behind at the state and the national level.

Zenith of Left Politics in India

The popularity of Left politics in India was at its height during the 1990s and early 2000s when the parties led governments in three states- Kerala, West Bengal and Tripura- and had a parliamentary strength of around 55 to 60 seats. The communist parties held kingmaker roles for the Third Front governments during 1996–98 and the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) between 2004 and 2008.

During this period, the Left Front alternatively formed governments in Kerala, giving way to Congress after each 5-year term. In West Bengal, the CPI (M) under Jyoti Basu’s leadership consolidated its rule and held on to power for 34 years between 1977 and 2011. After a series of policy decisions dented its pro-worker image, it was wiped out from West Bengal in 2011 by the Mamata Bannerjee-led All India Trinamool Congress (AITC). In Tripura, the CPI (M) came to power in 1988. Except for a brief moment of Congress rule between 1992 and 1998, the state was governed by the Left up until 2018 when the BJP unseated it from power.

The CPI and CPI (M), as the leading parties of the Left Alliance, put up their best performance in the 2004 Lok Sabha Election when they secured 53 seats. Both the parties, under the banner of the Left, supported the UPA I in 2004. The Left has also been partly attributed to the UPA I’s success as it managed to push its socio-economic agenda through the Manmohan Singh government. However, the alliance’s decision to withdraw its support to the UPA II in 2008 accompanied a series of events that finally diminished their influence in Indian politics.

The Decline of the Left

The Left’s decline in the states of West Bengal and Tripura and at the national stage is often associated with some poor decision-making by the left-wing parties. In 1996, when the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government failed to secure a vote of confidence after the Lok Sabha Election, a coalition of regional parties offered prime ministership to CPI (M)’s Jyoti Basu but the party declined the offer.

The Singur Land Acquisition in 2006 for the Tata Nano Project was another reason that may have led to the party and the Left Front’s downfall in India and more specifically West Bengal. The CPI (M)-led government’s hardstand and decision to evict protestors from Singur allowed Mamata Banerjee led-TMC to launch a struggle against the state government. It severely damaged the left party’s pro-poor and pro-worker image and catapulted Trinamool to the center of politics in West Bengal.

In the 2009 Lok Sabha (LS) Election, the Trinamool Congress (TMC) led by Mamata Bannerjee obliterated the Left Front in West Bengal. TMC won 18 parliamentary constituencies, storming communist strongholds in nine seats where the Left was undefeated in the past ten elections. Overall, the CPI (M) won 16 seats while the CPI won 4 seats down from 43 and 10, respectively in the 2004 LS. In the 2011 Assembly Election in West Bengal, the Left faced a further decline as its three-decade-old government lost power to the TMC and set the stage for its waning prominence in the state it once dominated.

In 2014, the Left recorded its lowest ever performance in a parliamentary election as it won 11 seats in only three states. This was a significant decline in its presence from the 1971 Lok Sabha election when it won seats from 10 states and the 2004 Lok Sabha Elections when it managed to win 59 seats. However, the Left Front’s ability to retain power in the 2016 Assembly Election in Kerala is the only major achievement amidst its other failures. In 2018, the CPI (M) lost more ground as it lost power in Tripura. This defeat raised a serious question about the future of Left politics in the state and India. In a way, it also questioned the extent to which the ideology of Marx and leftist politics had been effective in improving the practical realities of everyday life in the country.

The Left’s declining position in the politics of India was further aggravated in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections as its vote share dwindled from 29% in 2014 to about 7% in 2019. In the 2021 Assembly elections, the party was completely washed out in West Bengal as it failed to win even a single seat. In a first since independence, the Left will have no representative in the West Bengal state assembly.

However, the alliance broke records in Kerala in the 2021 Assembly Elections by becoming the first incumbent state government to be re-elected. In Tamil Nadu, both parties are a part of the ruling Secular Progressive Alliance led by the DMK which came to power in 2021. The CPI (M) also has representation in the Legislative Assemblies of Tripura, Assam, Rajasthan, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, and Maharashtra.

The Left’s Main Constituency and Loss of Base

The politics of the Left is centered around the working class- the peasants, farmers, and labourers. Since the emergence of Leftist politics in India, the left parties, mainly the CPI and CPI (M), have sought to apply Marxism-Leninism to Indian conditions aimed at transforming the lives of the working class. They have mainly relied on the support of farmers and landless labourers and in the past, their welfare policies have often drawn voters towards them.

Several parties who are a part of the left alliance have led peasants and student movements in different states and universities across India. The Naxalbari Movement in West Bengal in 1967 was led by the CPI (M) and Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI (M-L)). The All India Coordination Committee of Communist revolutionaries, which later converted into the CPI (M-L), spearheaded the 1967–90 Srikakulam Peasant Uprising in the Telangana region.

More recently, the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), affiliated with the CPI(M) led the JNU Fee Hike in 2020. The Anti-Citizenship Amendment Act & Anti-National Register of Citizens Protests of 2019–2020 were led by the All India Students Federation, the SFI, Chhatra Bharati and other left-wing student organisations. The protests which began in Assam and later made their way across the country received initial support from the Left-wing parties like CPI and CPI (M).

The CPI (M) has also led several local social movements at the ward level in both Bengal and Kerala, where party members visit local people to ensure proper communication. The Left’s overall agenda of welfare policies have also drawn voters towards the party, especially in Bengal where the Left Front has enjoyed a significant following among rural Bengal and its minority communities. However, of late the party and the left alliance have failed to convert this support base into electoral success. It has also failed to convert the support of younger voters into electoral benefits. This is despite the historically strong presence of the youth in the party’s membership and ranks.

The CPI (M)’s support for protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act are cited as one of the main reasons why the party drew support from a large section of the Muslim community in Kerala, which has traditionally supported the Congress-led United Democratic Front in the state. Owing to this, the party was able to increase its support base amongst the Muslims and Christians in Kerala, the last stronghold of the left.

Left’s Future in Indian Politics & the Need to Reinvent

According to analysts, the Left’s inability to reinvent itself and its stubbornness to stick to the theories and slogans that defined their movement decades ago has made it obsolete in 21st-century politics. Moreover, in the CPI(M), the inability of the party leadership to rise above petty intra-party tussles has highlighted the fault lines in the organization. In a country with a burgeoning young population, the CPI (M) has failed to mobilize the support of the youth. Only 6.5% of its members are below 25 years of age. Moreover, both parties’ inability to reform the party structure from within, lead campaigns relevant to the people and weed out corruption within its ranks are cited as some of the reasons behind their continued decline.

While the Left Alliance’s prospects have declined in states across the country and at the National level, the greater concern for it and mainly for the CPI (M) has been the loss of West Bengal, its former bastion for three decades. The party’s absence in the larger political discourse of the country is marked not only by the reduced numbers in state and Lok Sabha elections but also by the waning political influence and voice in the public discourse.

To bring the Left back to the center stage of politics in India, there is a pressing need for the party and the alliance to adopt a new approach to tackle ongoing socio-political issues. It needs to introspect on its organizational setup and establish goals that will focus on retaining not only its old electoral base but also capture new vote banks to enable it to come back from the periphery of Indian politics.

Damini Mehta /New Delhi

With inputs from Akansha Makker, Kashish Babbar, and Kavya Sharma, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.