The Seven Phase Fight for Uttar Pradesh: Phase 1 & 2

To make any considerable dent in the BJP’s attempts to consolidate the Hindu vote, the SP has to synthesize support across the Muslim, backward communities and farmers on several seats in western UP.

With eighty Lok Sabha seats, Uttar Pradesh (UP) comprises a little over 15 per cent of the composition of the lower house in the Parliament. Its electoral and political clout in the national discourse overshadows the presence of all other states. 403 Assembly seats are going to polls in February-March 2022, and the first phase of the seven-phase 2022 Uttar Pradesh Assembly election is already underway. According to political analysts, assembly elections in UP will likely have a direct impact on the Presidential elections in late 2022 and the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections.

The state, the fourth largest in India area wise, hardly behaves like a homogeneous entity while voting. It has a diverse population with strong regional and local identities ranging from Purvanchal in the east to Bundelkhand in the south. Variation in economic development and social composition further add to the diversified voting trends and patterns in its various regions.

In 2017, western UP, which is dominated by Jats and Muslims, the traditional vote banks of the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) and the Samajwadi Party (SP), respectively, moved towards the incumbent Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) en bloc, a pattern significantly different from the 2012 polls. On the other hand, eastern UP, which goes to the polls in phases six and seven in March 2022 and lacks the basic infrastructure and development that the western part of the state has witnessed over the years, voted on very different lines. Water-parched Bundelkhand is traditionally known to lean towards the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), however, in 2017 majority of the seats from this region went to the BJP. The diversity in social composition, plethora of small and mainstream political parties and predominance of the caste factor make elections to the Hindi heartland of India an interesting observation.

Phase 1: Will the SP-RLD’s Social Engineering work?

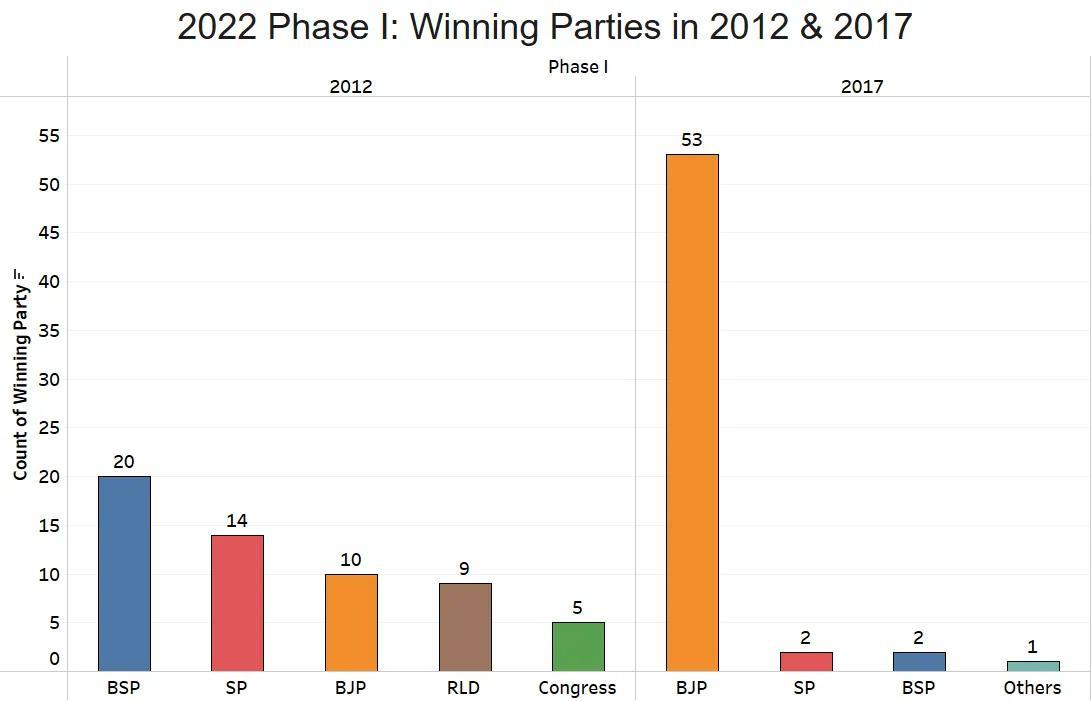

A part of the Jat and Muslim dominated western UP, also known as Paschim Pradesh went to the polls in the first phase of the UP Election on 10th February 2022. Fifty-eight assembly segments spread across eleven districts voted in what is turning out to be a direct contest between the incumbent BJP and the SP-RLD alliance. The voter turnout in the first phase was recorded at 60.17 per cent. In 2017, seats in this phase had registered a combined voter turnout of 64.56 per cent. The BJP won fifty-three of fifty-eight seats in 2017 polls.

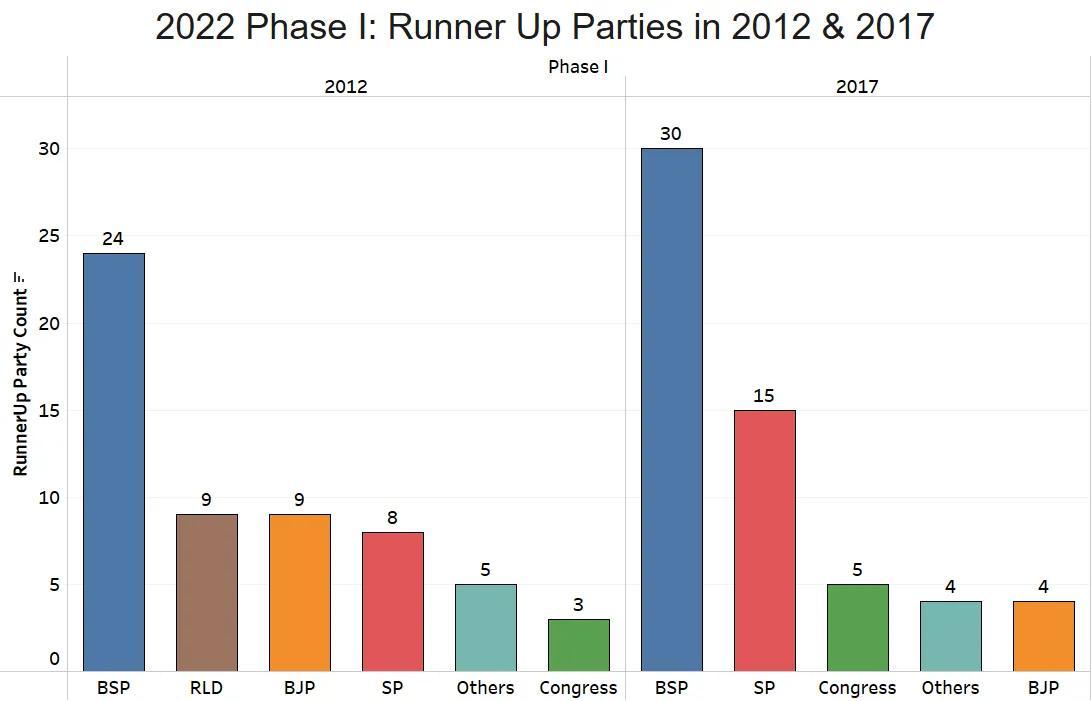

Both the SP and BSP won two seats each. The BSP came second on thirty seats with the SP ending runner-up on another fifteen. In 2012, the BSP dominated this phase winning twenty seats as it came second on twenty others. The SP won fourteen and the BJP ten that year. The RLD which won nine seats in 2012, was completely decimated in 2017, winning just one seat, the only seat it won in the entire state.

In a region where agriculture is the dominant occupation, and farmers’ concerns lie at the top of the list of poll issues, the BJP appears to be walking on eggshells. The year-long farmers’ protests against the three contentious farm laws witnessed large-scale participation of farmers from western UP.

While the central government repealed the laws in November 2021, resentment against the BJP remains high with the opposition leaving no chance to fan the disenchantment. To engineer a social alliance between the Jat farmers and the Muslims of the region, the SP has allied with the RLD. The SP is banking on its support amongst the Muslims and Yadavs coupled with the Jayant Chaudhary-led RLD’s stronghold in the Jat and farming community. Chaudhary is seeking to make a comeback in this region from 2017 when it secured a mere 1.8 per cent vote share in the state. Muslims comprise a little over 25 per cent of the population, while the Jats are anywhere between 14–17 per cent of the region’s population.

The 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, with the SP in power, created deep fault lines between the two communities as the former shifted en masse towards the BJP in all subsequent elections, from 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha to the 2017 Vidhan Sabha. In the 2014 General election, held a little over a year after the 2013 riots, BJP bagged all twelve Lok Sabha segments from here with the smallest victory margin across seats as high as 2.5 lakh. In 2019, it managed to retain eleven of the twelve seats, losing Bijnor to BSP. Moreover, in 2014, 2017 and 2019, the Modi wave helped the BJP consolidate the Hindu votes by rallying the Hindu community as it voted en masse for the Hindutva party. Several OBC castes are said to have risen above the caste lines and backed the BJP, turning against both the SP and the BSP.

With the farming and the peasant community in this region still up in arms against the BJP and the farmer unions such as Sanyukt Kisan Morcha actively emphasising the ‘anti-farmer’ nature of the BJP, the party is likely to face a tough battle in Phase one of the elections. It may lose a significant share of the fifty-three seats it won in 2017. It remains to be seen if the SP-RLD alliance will be able to convert its partnership into support on the ground by rallying the support of Muslims, Jats, Gujjars, Sainis and other backward castes, most of whom had previously voted for the BJP. According to reports, in several seats, locals and party workers from both the SP and the RLD are finding it hard to support the alliance candidate. Moreover, an aversion of Jat voters to the alliance’s Muslim candidates might pose another challenge for the combine if they want to mount any successful opposition to the BJP.

A Face-Off between the BJP and SP in Phase Two

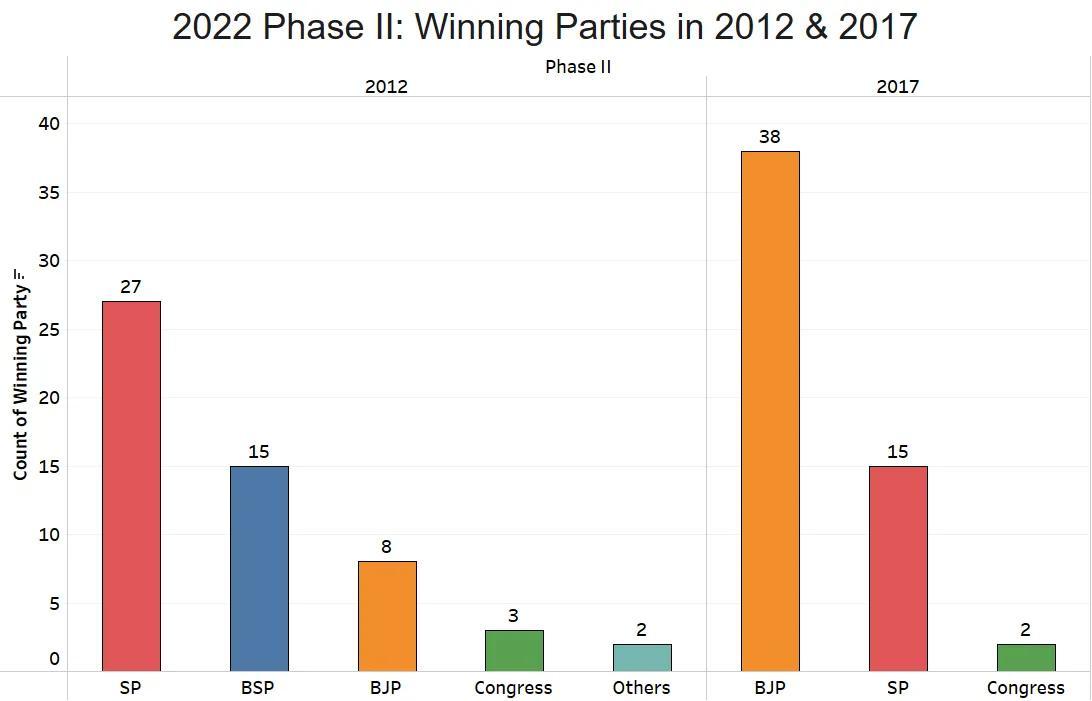

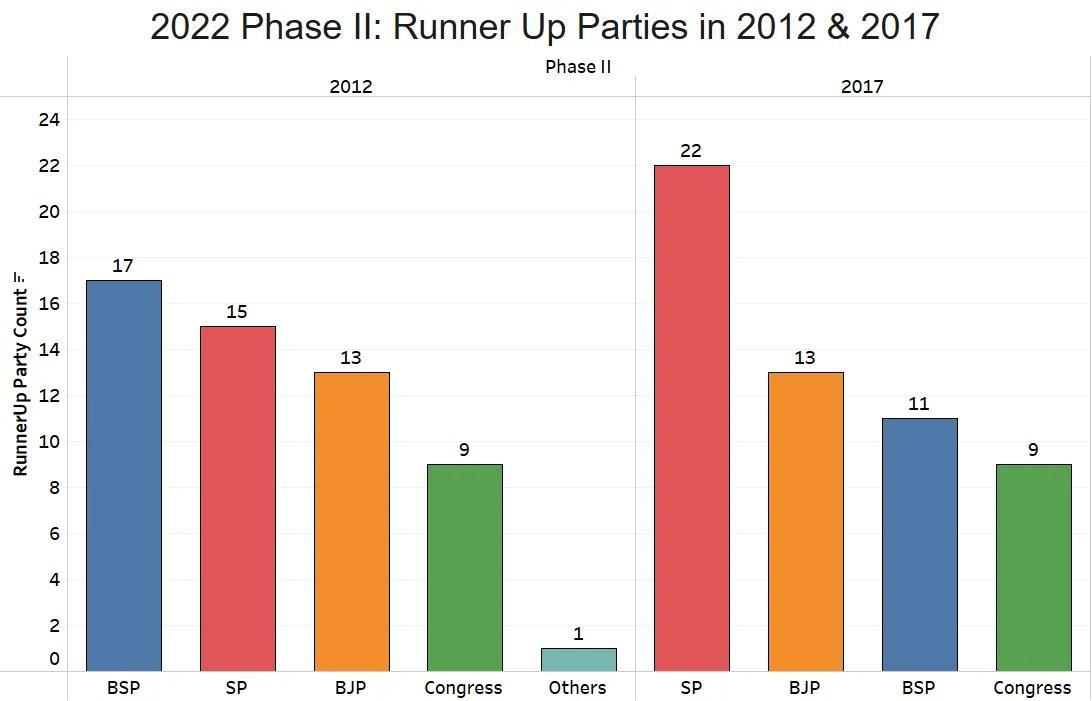

Fifty-five assembly segments in nine districts will vote on 14th February 2022 in the second phase of the 2022 UP Assembly Elections. Nine of the fifty-five seats are reserved for candidates from the Scheduled Castes. In the 2017 elections to the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly, BJP had secured thirty-eight out of fifty-five seats, a significant jump from the eight seats it won in 2012. It was the runner up on thirteen seats in the previous elections. The Samajwadi Party, which won half the seats in 2012, came down to just fifteen with second position on twenty-two others. The BSP, which won fifteen seats in 2012 was wiped out in 2017, emerging in second place on eleven seats. The INC decreased its tally from three seats in 2012 to two in 2017. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections saw fiercer competition. Out of the nine Parliamentary constituencies in this phase, the BJP, SP and BSP secured three seats each.

Districts in this phase have a motley mix of social composition that variates the voting patterns and political support across constituencies. A significant population of the Saharanpur district comprises Muslims (42 per cent) and Dalits (22 per cent). The district also has a sizable chunk of Gujjar and Saini voters. BSP’s strong performance before 2012 was largely attributed to the support from Jatavs.

Moreover, in both 2012 and 2017, the SP’s performance was overshadowed by the Congress, as on several seats in the district, Muslim votes were divided between the SP, BSP and Congress. More recently, the district has witnessed a spate of defections that will likely impact the local dynamics. In January 2022, two members of Congress joined the SP, while the Congress MLA from Behat switched to the BJP. BJP MLA from Nakur, a former member of the Adityanath Cabinet, also switched to the SP.

Dhampur constituency in Bijnor district has alternated between Ashok Kumar Rana, the incumbent BJP MLA and Mool Chand Chauhan from the SP. Rana was a BSP MLA in 2007, whereas Chauhan is a three-time MLA (1996, 2002, 2012), each time on an SP ticket. Rana came second in both 2002 and 2012. However, this time around, the Samajwadi Party has fielded Naeemul Hasan, likely keeping the sizable Muslim population in mind. In the Rampur district, in news over the years due to SP’s Azam Khan, Rampur and Suar constituencies will witness a two-faced battle between long time political rival families. In Suar, SP’s Abdullah Azam Khan is up against the erstwhile Nawab of Rampur, Haider Ali Khan of BJP ally Apna Dal (Sonelal). In Rampur, SP’s Azam Khan, a veteran of UP politics, will contest against Nawab Kazim Ali Khan of Congress.

Over the years, the roughly equal population of Hindus (52.14 per cent) and Muslims (47.12 per cent) in the SP stronghold of Moradabad district has impacted the choice of candidates for the political parties. While the BJP has chosen an all-Hindu roster for the upcoming elections, SP has sided with its traditional Muslim vote base and fielded only Muslim candidates from the six segments in this district. In 2012 and 2017, the SP won four of six seats in the district.

However, with other parties such as the BSP, Congress and AIMIM also fielding candidates from the community, the SP faces strong competition with the likelihood of Muslim votes dividing across parties giving a direct edge to the BJP.

The resentment due to rising prices, farmers’ concerns and attacks on minority communities have cast a shadow on the incumbent BJP’s ability to repeat its 2017 and 2019 victory. To make any considerable dent in the BJP’s attempts to consolidate the Hindu vote, the SP, which has emerged as the principal opposition party, has to synthesize support across the Muslim, backward communities and farmers on several seats in western Uttar Pradesh in phase one and phase two of the elections.

Damini Mehta /New Delhi

Data Visualization by Prakhar Yadav and Vaishali Ujlayan.

With inputs from Abhinav Nain, Muskan Dhawan, and Siddharth Malik, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.