Where are the Naga peace talks headed after the recent ceasefire?

The peace talks have gotten back on track after the recent headways, the central question here is that with multiple Naga factions still out of the peace accord, where is the peace process on the Naga conflict headed after this major change in leadership.

On 8th September 2021, the Centre signed a ceasefire agreement with the Niki Sumi faction of National Socialist Council of Nagaland Khaplang (K), one of the many factions of the larger Naga representative body, National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN). The ceasefire came through just a few weeks after Assam governor Jagdish Mukhi was given the additional charge of Nagaland. According to experts, the agreement was a step in the direction of bringing one more party to the conflict at the negotiating table. However, the need to assign Mukhi additional charge of Nagaland was seen as a culmination of the center giving in to the demands of the Naga groups to remove then Governor of Nagaland R.N Ravi.

The genesis of the Naga conflict lies in the tribal nature of the community and their prolonged desire to manage their affairs by their own norms and standards. The assimilation of the territory into the Indian socio-political framework began with the independence of India, when it was made a district of Assam. However, the division of the members of the community across the states of Nagaland, Manipur, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh and even neighbouring Myanmar, has made it difficult for an agreeable solution to be reached.

While the peace talks have gotten back on track after the recent headways, the central question here is that with multiple Naga factions still out of the peace accord, where is the peace process on the Naga conflict headed after this major change in leadership. In light of the recent developments, it’s important to understand the origins of the Naga conflict, one of the longest territorial conflicts in modern India, and what lies ahead for the Naga tribes, as factionalism riddles the various groups claiming to represent the larger Naga identity.

A conflict bred in part by the British

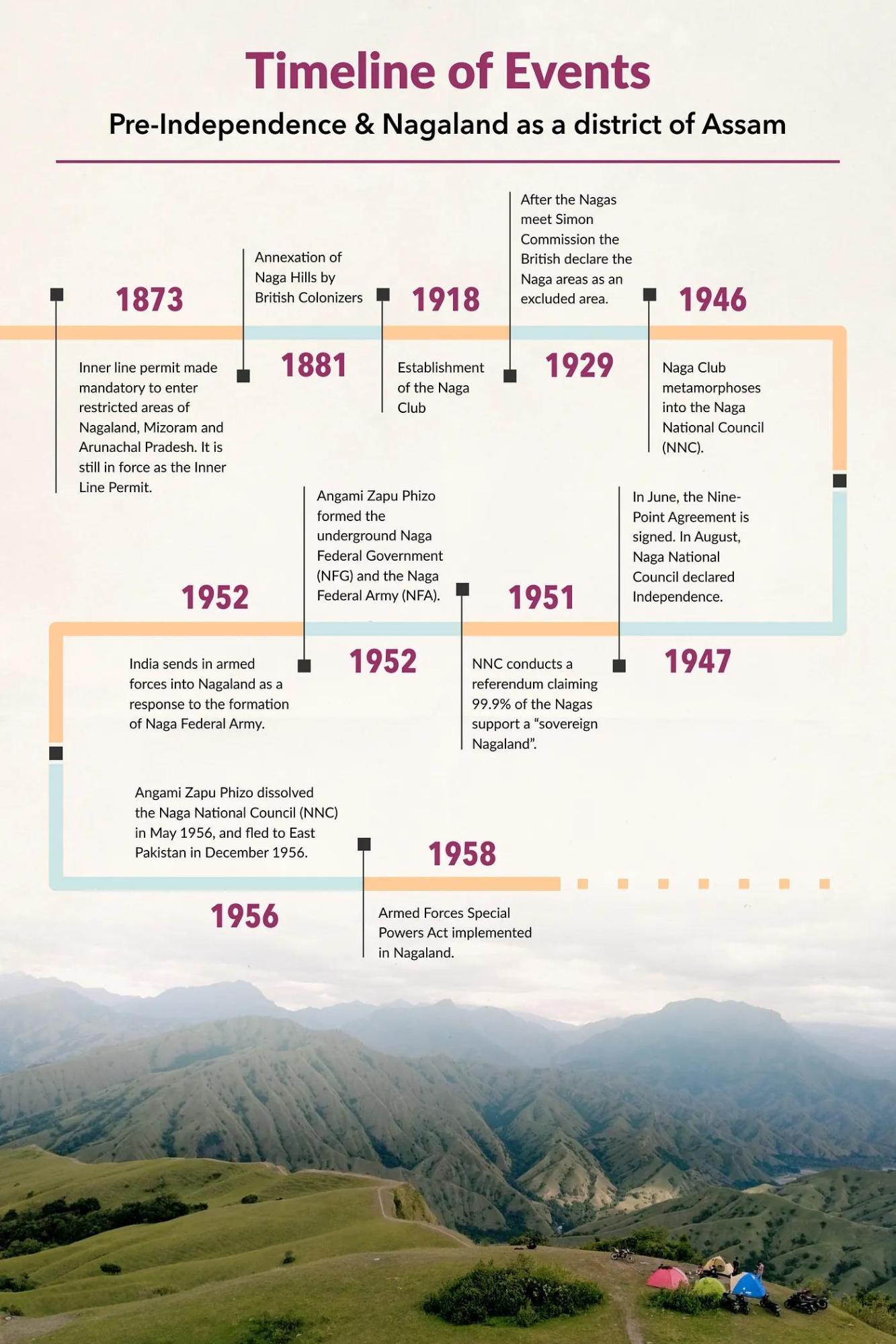

The Naga issue predates India’s independence. By some accounts, its origins can be traced back to 1873 when the Britishers established the Inner Line Permit rule making it mandatory to have a permit before entering restricted areas of Nagaland, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh. It was directed at preventing people of the plains from entering the Naga areas (except for Christian missionaries) to protect the Naga tribal identity. According to historians, it is considered as one of the preeminent factors which led to the Nagas’ estrangement from the mainstream Indian identity. In one way, the British policy of “least interference” has helped preserve the Nagas’ traditional way of life. However, the lack of contact with the mainland has also kept the Nagas away initially from the freedom movement and later on, the larger Indian identity.

Over the next few decades after the 1873 rule, the British government came face to face with the identity issues of the Naga tribes on more than one occasion. The transition of the Naga Hills Tribal Council, set up in April 1945 for relief and rehabilitation after the Second World War, into the Naga National Council (NNC), was a milestone in the Nagas’ struggle for identity and recognition. The council, formed to frame the terms of the relationship with the new Indian government after the withdrawal of the British, changed the face of the Naga struggle. NNC, characteristically a political outfit, marked the first time the Nagas floated the idea of their nationality. In June 1946, it passed a resolution against the grouping of Assam with Bengal. The group instead wanted the Naga hills to be included in Assam in independent India along with a promise of wide-ranging autonomy in the management of the internal affairs of the tribe.

By August 1947, seventeen Naga tribes and nearly twenty sub-tribes united under the aegis of the Naga National Council (NNC), protesting to demand for an independent Nagaland. To establish its sovereignty, the NNC, under the leadership of Angami Zapu Phizo, declared Nagaland an independent state on August 14, 1947. Phizo, considered the father of the Naga insurgency, was a hardline Naga who wanted nothing short of complete independence for the tribe.

Post-Independence Naga Struggle

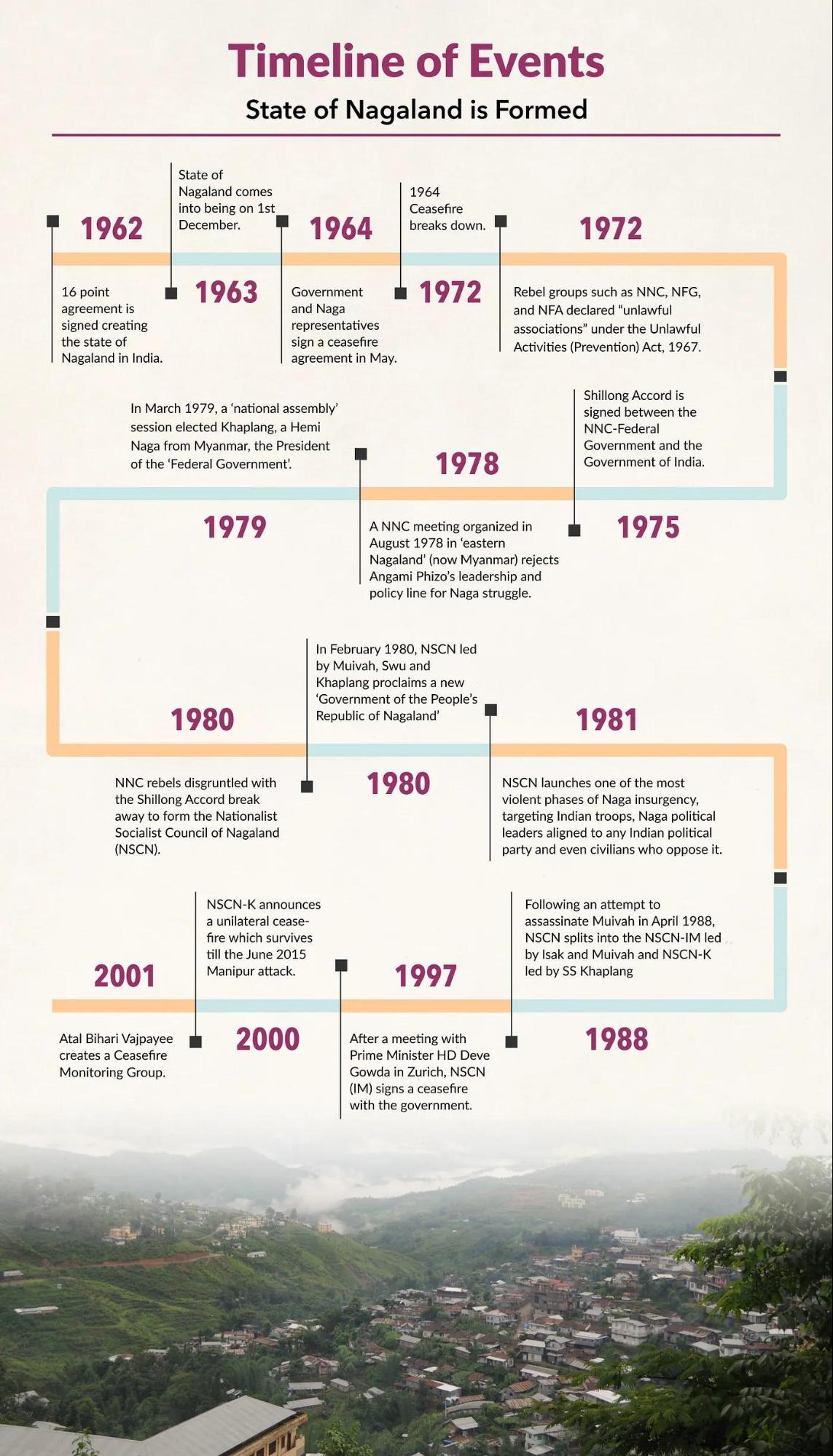

Since independence, several attempts have been made by the Central government to reach a common point of agreement with the revolting Naga tribes. The conflict reached a stage of agreement on more than one occasion, including the 16 point agreement in 1962 which led to the creation of the state of Nagaland. The negotiations have also witnessed several moments of relative calm and confrontation with the signing of ceasefire agreements and eventual implementation of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), respectively.

While the focus of the Indian government has been on integrating the Nagas into the Indian socio-political framework, the Naga tribes and groups have made wide-ranging demands over the years. The initial focus of the dominant Naga groups was on forming an independent Naga state reflected in the 1951 resolve of the NNC to establish a “sovereign Naga state” apparently justified through a “referendum” it conducted in 1951, in which “99 percent” supported an “independent” Nagaland.

In 1952, Phizo, an Angami Naga from Khonoma village near Kohima formed the underground Naga Federal Government (NFG) and the Naga Federal Army (NFA). In retaliation, the Government of India sent in the Army to crush the insurgency and, in 1958, enacted the AFSPA. The Indian government’s decision to form a separate state of Nagaland was seen as an attempt to give shape to the Naga demand for greater autonomy, given the region was only a district of the state of Assam till then. It, however, failed to bring an end to the insurgency in the state.

By the mid-twentieth century, several rebel groups emerged in the state, all claiming to represent the larger Naga identity in an attempt to exact varying demands of political power and socioeconomic concessions from the government. According to analysts, the existence of multiple rebel groups in the tribal community is one of the major issues that has prevented a peaceful resolution to the Naga conflict. While the central government has used this opportunity to negotiate with the more amiable groups, it has often tightened its grip on the violent factions. Amidst the power struggle, the real loss has been for the people of Nagaland.

The Suspension of Operation agreement signed in 1964 raised some hopes of finally reaching a peaceful solution. However, heightened insurgency in the years leading up to 1972 compelled the center to declare rebel groups such as NNC, NFG, and NFA “unlawful associations” and ban them under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), 1967.

Birth of NSCN & consequent Insurgency

The fall-through of the Shillong Accord, signed between the Centre and a section of the NNC and the NFG in 1975 changed the contours of the Naga conflict. The Accord led both the groups to accept the Indian constitution and surrender their weapons, coming closest ever to integrating with the Indian political framework. However, the inability of the Naga groups to unite under one umbrella led to the fall of the accord. A group of about 140 activists of the NNC, then training in China, rejected the Accord and formed a splinter organization in 1980, calling themselves the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN). The rise of the NSCN has marked the onset of Naga rebel groups as we see it today.

The emergence of NSCN in Nagaland’s political ground also underlined the beginning of the state’s most violent phase of insurgency. In an attempt to fulfill its avowed goal of ‘Nagaland for Christ’, the NSCN targeted everyone, from Indian troops, Naga political leaders aligned to any Indian political party to even civilians who opposed it. However, in less than a decade of its formation, the outfit suffered a catastrophic split as it broke into the NSCN-IM led by Isak and Muivah and NSCN-K led by SS Khaplang, following an assassination attempt on Muivah in April 1988. Since then, both the factions have been in negotiations with the centre at one point or another.

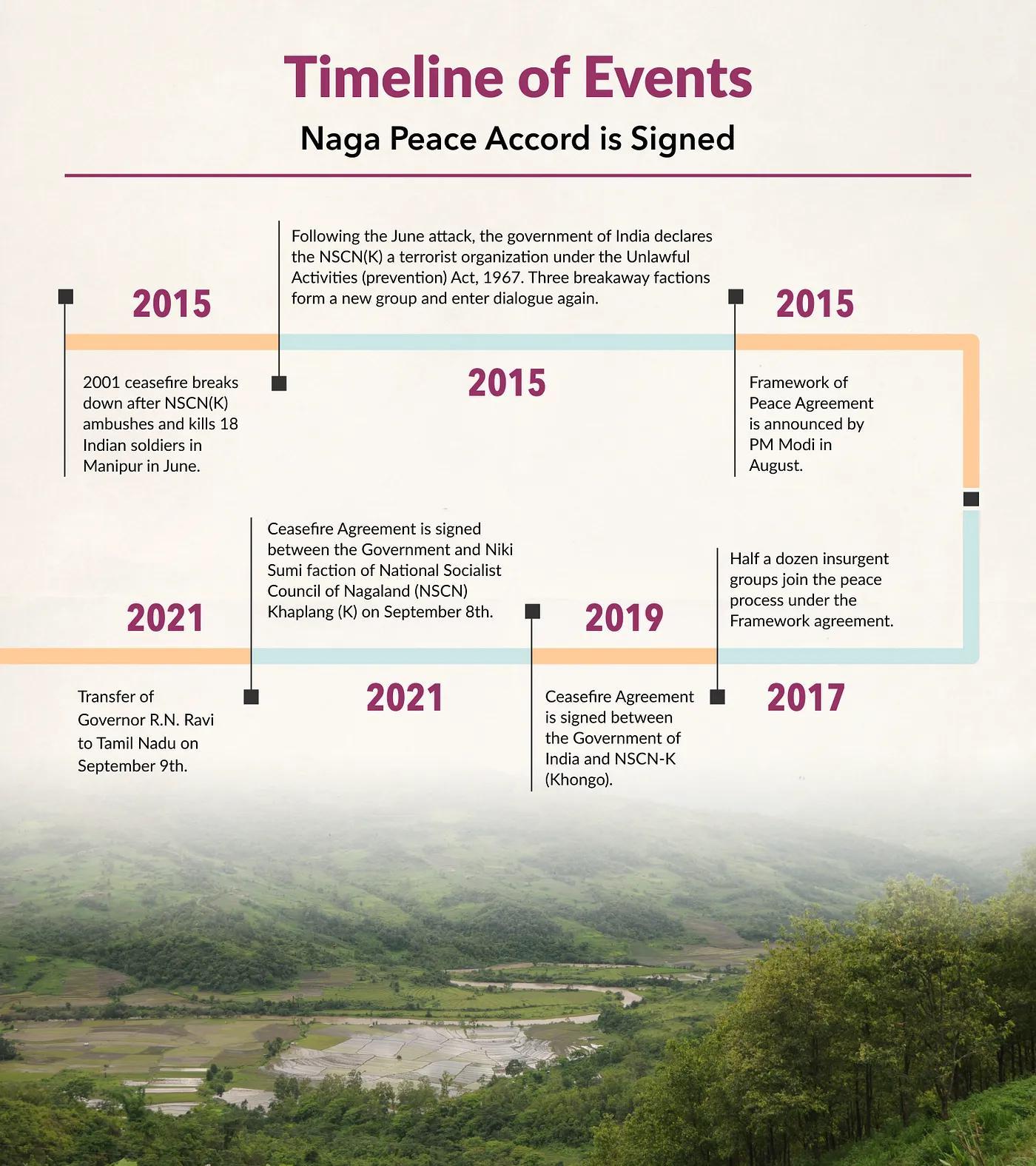

The ceasefire signed between the union government and NSCN (IM) in 1997 marked the onset of the longest-running peace talks in India. It set the stage for a reformed set of demands by the Naga group- recognition of the “unique history” of the Nagas; repeal of the AFSPA in Nagaland; territorial integration of all Naga areas; and a Naga constitution that would cover governance in the integrated “Nagalim.” The 1997, ceasefire was followed by a unilateral ceasefire by the NSCN-K in 2000 which survived for nearly 15 years, till the NSCN-K ambushed and killed 18 Indian soldiers in Manipur in June 2015. In the aftermath of the attack, the government of India declared NSCN (K) a terrorist organization under the UAPA.

The next one and a half-decade saw several attempts made by Prime Ministers Atal Bihar Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh to bring an end to the conflict.

2015 Agreement and the Road Ahead

In August 2015, a little over a year into the government at the center, the Narendra Modi-led BJP signed a framework peace agreement with the NSCN (Isak-Muivah), a dominant faction of the larger NSCN. On behalf of the government, the agreement was signed by the Center’s interlocutor for Naga Peace talks since 2014, R.N Ravi. The agreement was touted as a landmark, slated to end more than a century-long Naga territory issue carried over to India from the British Raj. However, Ravi’s tenure as interlocutor, and governor of Nagaland after 2019, was marked by a spate of controversies. Trouble began as Ravi’s infamous letter to the state’s Chief Minister which led to his fallout with NSCN (IM), was leaked in June 2020. In the letter, Ravi alleged that the state government had been a “mute spectator” as “armed gangs” engaged in extortion and violence in the region. He also alleged that “law and order” in Nagaland had collapsed. The NSCN-IM responded to Ravi’s letter, saying they ran a legitimate government and charged legitimate taxes.

In August 2020, another controversy emerged as the NSCN (IM) released copies of the confidential Framework Agreement and the Naga groups insisted on changing the interlocutor. The release of copies of the agreement, kept confidential by the center till then, culminated in a chain of events that led to the removal of Ravi. Since then, the peace process has seen several ups and downs. While the initial agreement left the Khaplang faction out after the center declared it a terrorist outfit (it is the prime accused in the 2015 Manipur Ambush), three breakaway factions formed a new group and entered the dialogue again.

The peace accord has sought to bring other Naga groups in its ambit as it was extended to include Naga National Political Groups (NNPGs), a group of seven insurgents who signed a Deed of Commitment with the Centre in 2017. Since then the 2019 ceasefire agreement between the Government of India and NSCN-K (Khongo) and the 2021 ceasefire between the Government and Niki Sumi faction of NSCN Khaplang (K) has opened doors for greater cooperation.

The signing of several ceasefire agreements and headways made with the other rebel groups are being seen as a positive step for the Naga peace process. It is in the backdrop of the appeals made by the Naga civil society to all the political groups to come together and chalk out a path to bring the long-pending Naga political issue to an amicable end.

Damini Mehta /New Delhi

Contributing reports from Abhinay Chandna and Kashish Babbar, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.