Will the National Farmers’ Database really double farmers’ incomes?

Note: The original version of this article was published on September 15th, 2021 in “The Daily Guardian”

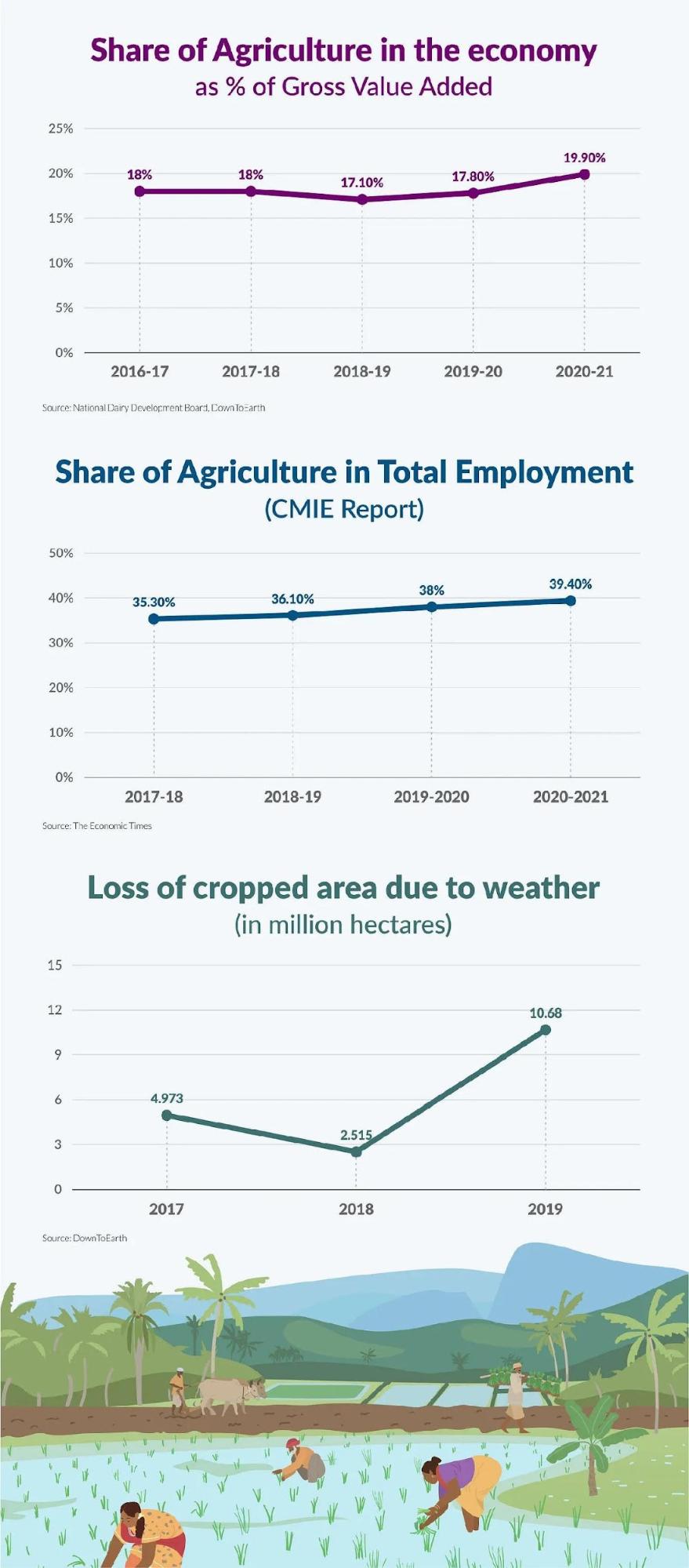

Earlier in September, Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar announced the creation of a National Farmers’ Database containing the records of over 5.5 crore farmers. Tomar also announced that the number of farmers included in the database would increase to 8 crores by December 2021 by linking it with state-wise land record databases. This initiative is part of Agristack, a collection of technologies and digital databases on India’s farmers and the agricultural sector. These are being built by the central government to help farmers tackle issues such as poor access to credit and wastage in the agricultural supply chain, which continue to plague farmers across the country. The government has also created the India Digital Ecosystem of Agriculture (IDEA) which will lay down a framework for Agristack.

The Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare (DoAFW) claims that the digitized system will help offer proactive and personalised services to farmers, thereby increasing their income and improving the efficiency of the agricultural sector. However, experts have raised concerns about the digital divide between farmers, lack of push for crop diversification and representation of farmers in the India Digital Ecosystem of Agriculture (IDEA) task force, which could defeat the purpose of having such a database.

What will be the use of a National Farmers’ Database?

India has 14 crore operational farmland holdings and the maintenance of proper land records, especially in rural areas, has been a major challenge for the government in introducing and implementing welfare policies for farmers. The availability of a database consolidating these records would be an important stepping stone in the formulation of evidence-based policies for the agricultural sector. Under the programme, each farmer of the country will get what is being called an FID, or a Farmers’ ID, linked to land records to uniquely identify them. An important point to note is that the database would be linked to a digital land record management system, and so would only include farmers who are legal owners of agricultural land. Landless farmers will not be included in the database.

As part of the database, farmers would have access to personalised services, such as DBT, social and plant health advisories, and weather advisories. It would also aim to facilitate seamless credit and insurance, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticide-related information. The national database has been created by taking data from existing national schemes such as PM KISAN, soil health cards, and the insurance scheme PM Fasal Bima Yojna. The creation of the National Farmers’ Database will serve as the core of Agristack and IDEA, making data easily available and opening up the possibility of implementing digital technologies like AI/Machine Learning, Internet of Things (IoT) in the agricultural domain. The database would potentially contribute to ensuring input costs are reduced, ease of farming is ensured, quality is improved, and that farmers are able to get better prices for their farm produce, thus opening the sector up to productivity improvements.

Concerns associated with the database and IDEA

One of the glaring concerns of the database is the digital divide facing farmers in India. There is a huge digital divide between rural and urban areas in the country. According to the National Sample Survey conducted between 2017–2018, only 14.9% of rural households had access to the Internet against 42% of households in urban areas. The majority of farmers in the country live in rural areas and do not have access to smartphones, which means that they will not be able to enjoy the personalised purported benefits of the national database. Another concern of the database is that since it only includes farmers who are legally registered as landowners, it would leave out tenant farmers, landless labourers, and sharecroppers, who form a significant proportion of small and marginal farmers in the country. It would also exclude fisherfolk, livestock and dairy farmers without land, and those who collect forest produce. Various farmer groups have also pointed out that in most agricultural families, the land titles are typically in the name of the male head of the household. The Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017–18) in India states that in rural areas, 73.2% of the female workers are engaged in agriculture, but only 12.8% of women own landholdings, according to the Centre for Land Governance index.

Furthermore, farmers and farm organisations have raised objections to the IDEA task force, as there is a lack of farmer representation in the existing task force which was supposed to seek feedback from parties concerned. The farmers believe this process is similar to the way the three farm laws were introduced last year, with farmers not being consulted. A group of 91 farm unions and farmer organisations, including digital rights activists, have sent a feedback letter to the central government alleging that the current model is only focused on using pre-existing databases and would be geared towards corporate revenue models rather than ensuring that farmers’ needs and interests are considered. Agristack could also be misused for purposes such as predatory lending or land grabs.

Will the database double incomes?

The initiative to build a national database is a part of a report prepared by the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income (DFI). Under Volume 13, the report proposes to build a dynamic database and ensure targeted and efficient delivery of support to farmers, and to assist specialised extension services. For the last year, farmers have been protesting against the three farm laws introduced by the central government at the borders of the national capital, which has triggered a lot of debate around problems in the agricultural sector in the country. The poor economic condition of farmers across the country is a huge part of the problem. A survey conducted by Lokniti in 2014 showed that around 40% of farmers were dissatisfied with their economic conditions. The figure was more than 60% in eastern India and more than 70% of farmers said they think city life was better than village life.

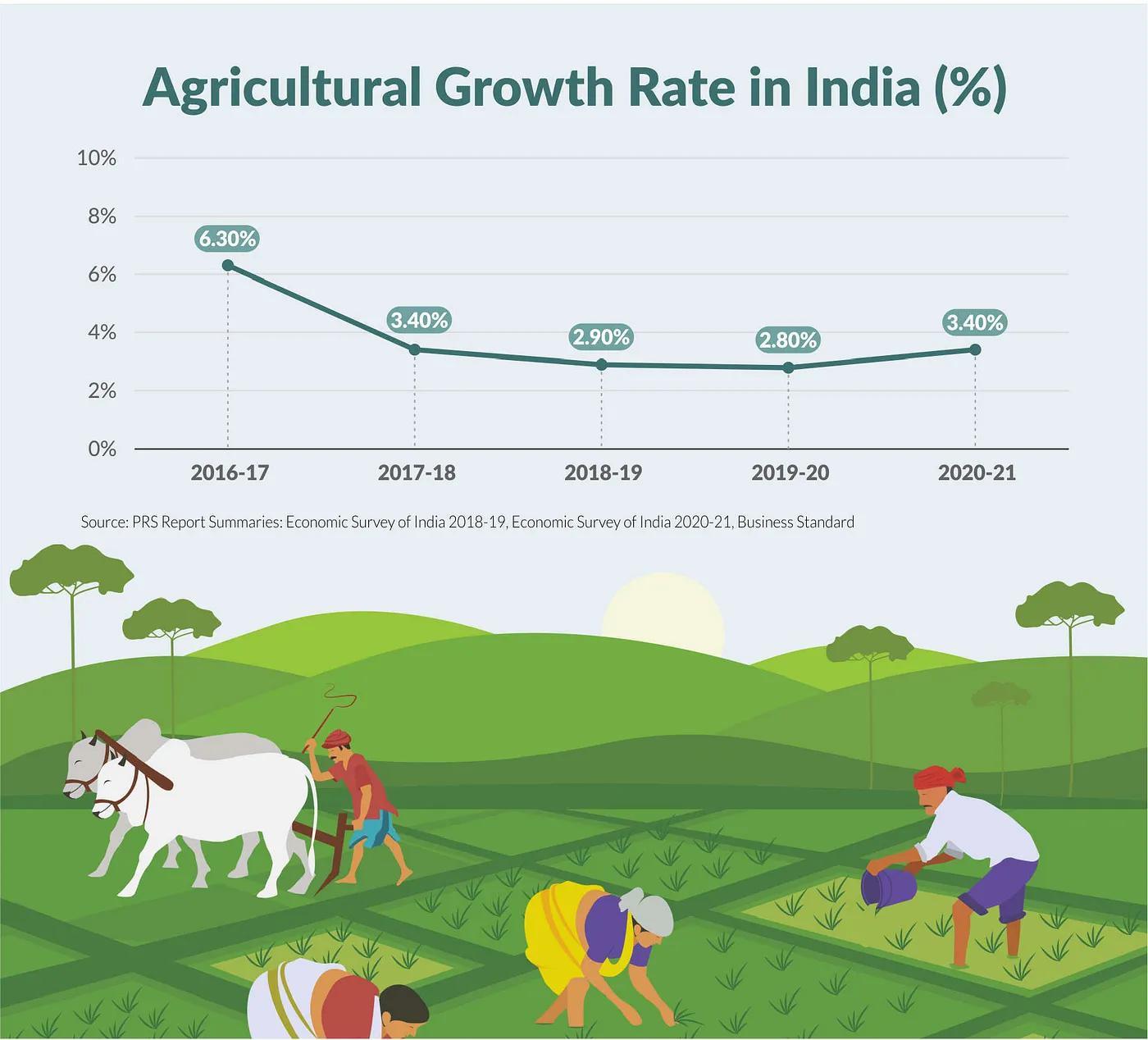

The lack of a coherent farm policy that addresses both the issues of sustainability and long term productivity growth in the sector has been brought up many times by farmers, farmer unions, and other stakeholders. Many agricultural scientists pointed out that crop productivity has reached a saturation point in many states, especially in the “food bowls” of Punjab, Haryana, and Western UP, where only rice and wheat crops have been grown for the past few decades due to governmental policies. While costs of agricultural inputs have increased year after year, farmers have only been receiving increases in the minimum support price (MSP) for the two crops. Furthermore, the pattern in the area sown is completely guided by the variation in the monsoon season as a bad monsoon directly impacts the cost of cultivation and makes sowing of large areas unprofitable for the farmers. Similar issues are also linked with the production and yield of the kharif crops, which are rain-fed.

While in theory, the creation of a national digital database would help deliver personalised services to farmers and allow for the implementation of technology to improve productivity in the sector, the database itself would leave out the most vulnerable farmers in the country. Pushing for greater crop diversification, correction of commercial risks due to volatile prices, and removal of restrictions on the movement of farm produce markets are some of the measures that perhaps could help, alongside the constitution of a national database to ensure the on-ground problems of farmers are resolved and thereby leading to higher incomes across the sector.

Shreya Maskara /New Delhi

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Akansha Makker, Animesh Gadre, Damayanti Niyogi, Interns at Polstrat.

From Polstrat, a non-partisan political consultancy which aims to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.

Read more about Polstrat here. Follow us on Medium to keep up to date with Indian politics.

Polstrat is a political consultancy aiming to shift the narrative of political discourse in the country from a problem-centric to a solutions-oriented approach.